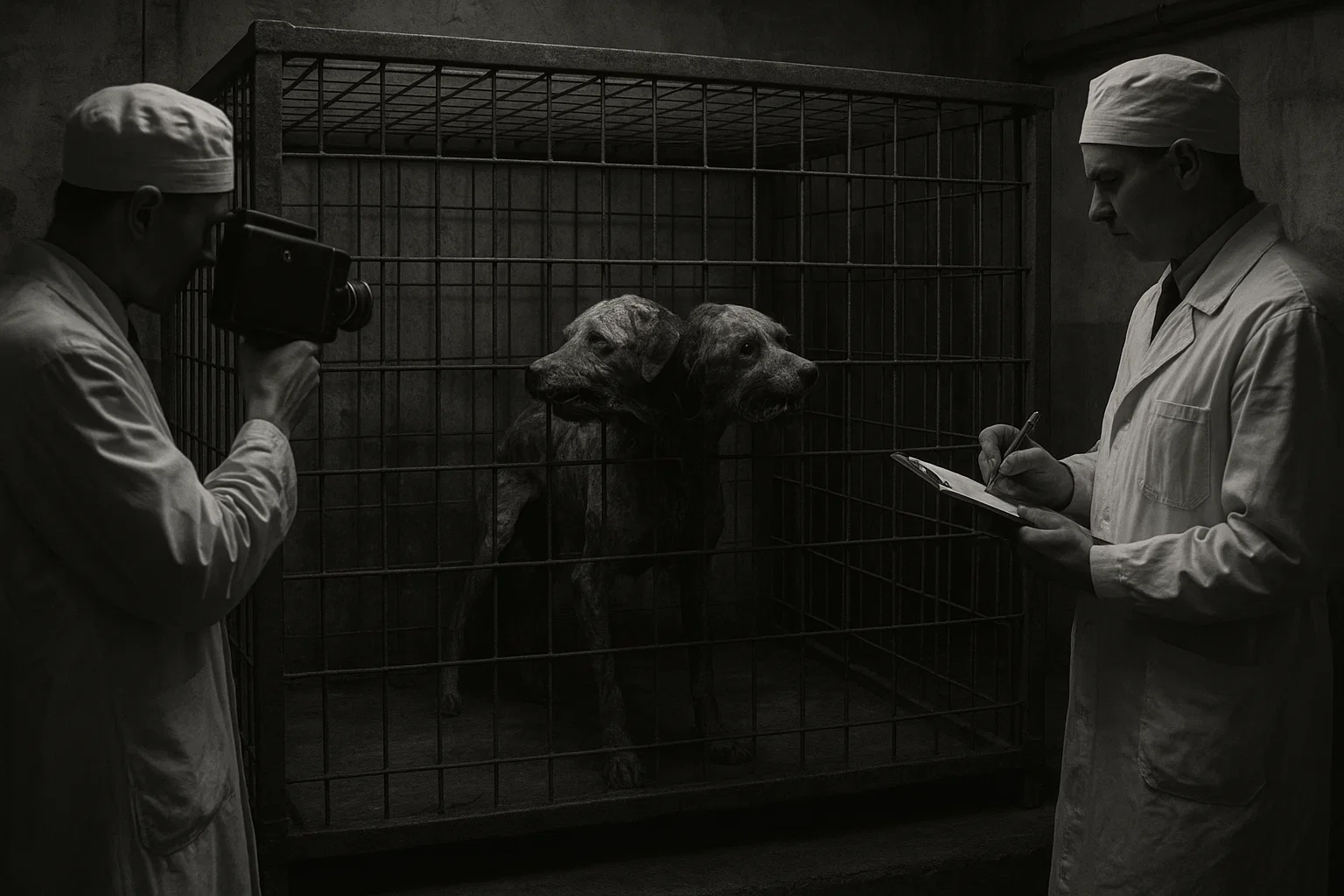

The two-headed dogs experiment, conducted by Soviet surgeon Vladimir Demikhov from 1954 to 1959, stands as one of the most audacious and ethically contentious endeavors in medical history.

At the Moscow Institute of Surgery, Demikhov grafted the head and forepaws of a smaller dog onto the neck of a larger dog, creating a living, two-headed organism.

Performed 23 times, these experiments aimed to advance transplantation science by exploring vascular anastomosis and organ compatibility. The most notable case, involving dogs named Brodyaga and Shavka, survived for four days in January 1959, while the longest-surviving pair endured 29 days.

Despite technical successes, the experiments sparked global outrage for their cruelty, with the Soviet Ministry of Health deeming them unethical. Demikhov’s work, while contributing to modern organ transplantation, remains a polarizing symbol of scientific ambition and moral controversy.

Summary

Overview

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Lead Scientist | Vladimir Demikhov, Soviet transplantation pioneer (1916–1998) |

| Time Period | February 1954–January 13, 1959 |

| Key Experiment | Grafting a smaller dog’s head and forepaws onto a larger dog’s neck |

| Location | Moscow Institute of Surgery; final experiment in Leipzig, East Germany |

| Number of Procedures | 23 documented procedures |

| Longest Survival | 29 days (host dog Pirat, January 1959) |

| Key Demonstration | January 13, 1959, Brodyaga (host) and Shavka (donor) |

| Ethical Controversy | Condemned by Soviet Ministry of Health; global protests for animal cruelty |

| Scientific Contribution | Advanced vascular suturing and transplant immunology |

Who Was Vladimir Demikhov??

Vladimir Petrovich Demikhov (July 18, 1916–November 22, 1998) was a visionary Soviet surgeon whose relentless pursuit of transplantation science reshaped medical possibilities.

Born in the rural village of Yarizhenskaya, Volgograd region, Demikhov grew up in a peasant family marked by hardship. His father, Peter Yakovlevich, a Cossack, perished in the Russian Civil War in 1919, leaving his mother, Domnika Alexandrovna, a schoolteacher, to raise Vladimir and his siblings.

Despite financial struggles, Domnika prioritized education, fostering Vladimir’s early fascination with biology, particularly the circulatory system. As a child, he dissected small animals to understand their anatomy, a precursor to his later surgical prowess.

Demikhov enrolled at the First Moscow Medical Institute in 1934, graduating in 1940 with a degree in medicine. During World War II, he served as a military pathologist in the Red Army, stationed near Stalingrad.

His wartime role involved autopsies and treating soldiers, some of whom inflicted wounds to avoid combat. Demikhov’s compassion led him to falsify reports, sparing these soldiers from execution—a risky act under Stalin’s regime.

These experiences, coupled with witnessing the devastation of war, fueled his determination to develop life-saving surgical techniques.

Post-war, Demikhov joined the Institute of Experimental and Clinical Surgery in Moscow, where he began groundbreaking experiments. In 1937, as a student, he designed a mechanical heart prototype, capable of sustaining circulation in a dog for five hours.

By 1946, he performed the world’s first dog heart transplant, followed by a heart-lung transplant in 1947. In 1953, he pioneered the coronary artery bypass, a technique now standard in cardiac surgery.

These achievements, detailed in his 1948 dissertation, earned him a doctorate from the Sklifosovsky Institute. Despite his brilliance, Demikhov faced professional isolation due to his unorthodox methods and Soviet bureaucracy, which often favored politically connected scientists.

Demikhov’s two-headed dogs experiment was his most controversial endeavor, driven by a desire to overcome immunological barriers in transplantation.

He worked tirelessly, often funding experiments from his modest salary, and lived in a small Moscow apartment with his wife, Lyudmila Alexandrovna, and daughter, Olga.

His later years were marked by obscurity; he retired in 1986 and died in 1998, largely unrecognized until posthumous tributes from surgeons like Christiaan Barnard and Michael DeBakey.

Demikhov’s 1960 book, Experimental Transplantation of Vital Organs, remains a seminal work, coining the term “transplantology.”

You May Also Like: Andromalius: The Sinister Earl of Hell

The Cold War Scientific Race

The 1950s were a pivotal decade in the Cold War, where the Soviet Union and United States competed fiercely in science, technology, and medicine.

The Soviet Union, under leaders like Nikita Khrushchev, invested heavily in bold experiments to showcase communist superiority, often prioritizing spectacle over ethics. Biomedical research, including transplantation, became a battleground for ideological supremacy.

Demikhov’s experiments built on earlier Soviet work, such as Sergei Brukhonenko’s dog head experiments (1925–1939), which sustained severed heads using an autojector. Meanwhile, the U.S. advanced heart-lung machines (e.g., John Gibbon’s 1953 surgery) and explored organ preservation.

Both nations pushed ethical boundaries, driven by the need to outpace each other in a post-World War II world. The Soviet system’s opacity allowed experiments like Demikhov’s to proceed with minimal oversight, while U.S. research faced growing scrutiny after the Nuremberg Code (1947) emphasized ethical standards.

The Two-Headed Dogs Experiment

From February 1954 to January 13, 1959, Vladimir Demikhov conducted 23 two-headed dogs experiments at the Moscow Institute of Surgery, with the final procedure performed in Leipzig, East Germany, as a public demonstration.

The experiments aimed to address critical questions in transplantation science: Could major body parts, like a head, be grafted onto another organism? Could a shared circulatory system sustain both?

Demikhov sought to refine vascular anastomosis—the surgical connection of blood vessels—and study immunological rejection, a major barrier to organ transplantation.

Surgical Methodology

The procedure was a complex feat of surgical skill, requiring precision under the technological constraints of the 1950s.

Demikhov, assisted by technicians like Maria Tretekova and Valery Ivanov, operated in a sterile laboratory equipped with rudimentary tools. The most documented case occurred on January 13, 1959, involving a large German Shepherd named Brodyaga (host) and a smaller dog, Shavka (donor).

The surgical process unfolded as follows:

- Preparation: Both dogs were anesthetized using sodium pentobarbital. Shavka’s lower body was amputated below the forepaws, preserving her heart, lungs, carotid arteries, and jugular veins. Brodyaga’s neck was shaved and incised to expose major blood vessels.

- Vascular Anastomosis: Shavka’s carotid arteries and jugular veins were meticulously sutured to Brodyaga’s corresponding vessels using silk threads. This allowed Brodyaga’s heart to pump blood to both heads, maintaining cerebral function. Demikhov used a vascular clamp to control bleeding during suturing.

- Structural Support: Shavka’s cervical vertebrae were anchored to Brodyaga’s neck with plastic strings and metal clips, ensuring stability without damaging spinal nerves.

- Anticoagulation and Monitoring: Early anticoagulants, such as sodium citrate, were administered to prevent clotting, though less effective than modern heparin. The surgical team monitored blood pressure and oxygen levels using a manometer and pulse oximeter.

- Duration: The procedure lasted approximately 3 hours and 20 minutes, with Demikhov’s team working under intense pressure to avoid air embolisms or vessel collapse.

Post-surgery, the two-headed dog was placed in a recovery cage, warmed with blankets to prevent hypothermia, and observed for signs of consciousness. The grafted head (Shavka) typically awoke within hours, displaying reflexive behaviors like blinking and swallowing.

You May Also Like: Kurupi — The Bizarre Jungle Spirit Blamed for Unwanted Pregnancies

Physiological Functionality

The two-headed dogs demonstrated an extraordinary capacity to function, albeit briefly, as a single organism with dual consciousness.

In the most documented case, involving the German Shepherd Brodyaga (host) and the smaller dog Shavka (donor) on January 13, 1959, both heads exhibited distinct sensory and motor capabilities.

Brodyaga, the host, retained full functionality, continuing to walk, eat, and respond to environmental cues as a normal dog would.

Shavka’s grafted head, sustained by Brodyaga’s heart through connected carotid arteries and jugular veins, displayed a surprising array of responses despite its severed lower body.

Sensory Capabilities

Both heads responded to external stimuli with remarkable clarity. Brodyaga’s head reacted to familiar triggers, such as the sight of food or the sound of a laboratory assistant’s voice, with typical canine behaviors like barking or ear twitching.

Shavka’s head, though limited by its lack of a full body, showed corneal reflexes (blinking when a light was flashed near her eyes), auditory responses (ear movements in response to a clapped hand or a loud whistle), and olfactory reactions (sniffing when exposed to strong odors like ammonia).

These responses suggested that the cerebral cortex and brainstem remained functional, supported by adequate blood flow from the autojector-inspired vascular connections.

Motor Functions

Shavka’s head could perform limited but significant actions. She was observed lapping water from a dish and attempting to swallow small pieces of food, such as bread or meat, placed near her mouth.

To prevent choking, her esophagus was surgically diverted to an external tube, as it was not connected to Brodyaga’s digestive tract. This tube allowed liquids to drain safely, a critical adaptation given the grafted head’s inability to process food internally.

Brodyaga, meanwhile, maintained normal motor functions, including walking, running short distances, and grooming, though his movements were occasionally hindered by the additional weight and bulk of Shavka’s head.

Neurological Integration

The grafted head’s ability to respond independently indicated partial neurological autonomy. Shavka’s head occasionally moved its jaws or eyes in ways that did not synchronize with Brodyaga’s actions, suggesting that her cranial nerves remained intact.

However, the lack of spinal cord reconnection meant that Shavka’s head could not control a body, limiting her actions to facial and oral movements.

This partial integration underscored the experiment’s primary focus: sustaining cerebral function through shared circulation rather than achieving full bodily coordination.

Behavioral Observations

The behavioral responses of the two-headed dogs were as compelling as they were distressing, revealing the psychological toll of the procedure. Both heads exhibited signs of discomfort and confusion, reflecting the unnatural state of their existence.

Shavka’s head frequently whimpered, a plaintive sound that Demikhov’s assistant, Maria Tretekova, noted in laboratory logs as occurring when Shavka was exposed to bright lights or sudden movements.

These vocalizations suggested pain or disorientation, likely due to the absence of her lower body and the sensory overload of being grafted onto another organism.

Shavka also attempted to move her head independently, jerking against the plastic strings and metal clips that anchored her vertebrae to Brodyaga’s neck, further indicating a struggle to adapt to her new reality.

Brodyaga, the host, displayed signs of stress and agitation. Laboratory records from January 1959 describe him snapping at Shavka’s head, particularly when her movements disrupted his own.

On the second day post-surgery, Brodyaga was observed pacing restlessly in his recovery cage, occasionally growling or attempting to scratch at the surgical site on his neck.

These behaviors suggested that the additional head imposed a significant physiological burden, both physically and psychologically.

Despite these challenges, Brodyaga continued to eat and drink, though his appetite was reduced, possibly due to circulatory strain or hormonal imbalances caused by the shared blood supply.

You May Also Like: Inokashira Park Curse: The Mysterious Park That Breaks Couples

Survival Times and Limitations

The survival times of the two-headed dogs varied widely, reflecting the experimental nature of the procedure and the era’s technological constraints.

Across the 23 documented procedures, the average survival was 2 to 6 days, with most dogs succumbing to a combination of immunological, infectious, and circulatory complications.

The Brodyaga-Shavka case, performed on January 13–17, 1959, lasted 4 days, making it one of the more successful attempts in terms of duration and public attention.

The longest-surviving pair, involving a host dog named Pirat and an unnamed donor, endured 29 days from December 15, 1958, to January 13, 1959, a remarkable feat given the era’s limitations.

Pirat’s survival was cut short by a damaged neck vein that led to severe edema (swelling) and subsequent tissue necrosis.

The primary factors limiting survival included:

- Immunological Rejection: The grafted head’s tissues, recognized as foreign by the host’s immune system, triggered an inflammatory response. This led to necrosis (tissue death) at the surgical site, particularly around the vascular sutures. Demikhov attempted to mitigate this with early immunosuppressants like cortisone, but these were rudimentary and often ineffective, as modern drugs like cyclosporine were not available until the 1970s.

- Infections: Surgical wounds were prone to bacterial infections, exacerbated by the limited availability of antibiotics. Penicillin, introduced in the Soviet Union in the 1940s, was used sparingly due to cost and supply issues, and sepsis was a common cause of death. Laboratory notes from 1955 describe one dog developing a staphylococcal infection within 48 hours, leading to fever and organ failure.

- Circulatory Strain: The host dog’s heart faced immense pressure to supply blood to two heads, resulting in hypertension and cardiac stress. In the Brodyaga-Shavka case, measurements showed Brodyaga’s heart rate averaging 120–140 beats per minute post-surgery, compared to a normal canine rate of 70–100. This strain often led to congestive heart failure, particularly in longer-surviving dogs like Pirat.

- Neurological Complications: The grafted head’s brainstem functioned, but prolonged survival risked ischemic damage due to inconsistent blood flow. Demikhov’s logs noted instances of seizure-like activity in some grafted heads, likely due to hypoxia or electrolyte imbalances in the shared blood supply.

Key Demonstrations and Documentation

Demikhov’s experiments were not confined to the laboratory; they were showcased at major scientific gatherings to demonstrate Soviet surgical prowess and attract international attention.

The first successful procedure, conducted on February 12, 1954, at the Moscow Institute of Surgery, was reported in the journal Soviet Medicine (March 1954 issue).

The article detailed a two-headed dog surviving 3 days, with both heads responding to stimuli, marking a milestone in transplantation science.

On June 15, 1955, Demikhov presented a live demonstration at the All-Union Conference of Surgeons in Moscow, where a two-headed dog survived 5 days. The audience, including prominent Soviet surgeons like Alexander Vishnevsky, was both awed and disturbed by the creature’s dual functionality.

The most publicized demonstration occurred on January 13, 1959, in Leipzig, East Germany, at the Karl Marx University Medical Faculty.

Attended by Soviet and East German scientists, including Professor Hans Gummel, the event featured Brodyaga and Shavka. Gummel, in a subsequent report dated January 20, 1959, praised the “masterful surgical technique” but criticized the experiment’s “ethical void,” reflecting the polarized reception.

The Leipzig demonstration was filmed using 16mm cameras, capturing Shavka’s head lapping water and Brodyaga walking unsteadily.

This footage, alongside still photographs, was included in a 1959 Soviet documentary, Advances in Soviet Surgery, and featured in a LIFE Magazine article on February 23, 1959, which described the experiment as “a chilling triumph of science.”

Demikhov meticulously documented his work in his 1960 monograph, Experimental Transplantation of Vital Organs, published by the Moscow Medical Press. The book, translated into English in 1962 by Basil Haigh, included detailed surgical diagrams, blood flow calculations, and post-operative observations.

It described the 23 procedures, noting specific cases like a 1956 experiment where a two-headed dog survived 6 days before succumbing to pneumonia.

The monograph also outlined challenges, such as vascular thrombosis (clotting), and proposed solutions like improved anticoagulants. These records, combined with photographic and film evidence, provided a comprehensive account of the experiments, ensuring their place in medical history despite their controversy.

You May Also Like: The Infamous Cursed Kleenex Commercial: Fact, Fiction, and Urban Legend

Was the Two-Headed Dogs Experiment Real?

The creation of a living, two-headed dog—achieved by grafting the head and forepaws of a smaller dog onto the neck of a larger one—seems almost fantastical, prompting skepticism from contemporaries and modern scholars alike.

However, a wealth of documentation, including surgical records, photographs, film footage, and eyewitness accounts, provides substantial evidence that the experiments occurred as described.

Controversies and Initial Skepticism

The two-headed dogs experiment provoked immediate controversy upon its public unveiling, particularly during the high-profile demonstration on January 13, 1959, at the Karl Marx University Medical Faculty in Leipzig, East Germany.

The procedure, involving dogs Brodyaga (host) and Shavka (donor), was attended by Soviet and East German scientists, journalists, and medical professionals.

While the live demonstration—where the two-headed dog walked, and Shavka’s grafted head responded to stimuli like light and sound—stunned observers, it also sparked intense debate.

Critics questioned whether the results were exaggerated, staged, or driven by Soviet propaganda to showcase scientific superiority during the Cold War.

The Soviet Union’s political climate fueled skepticism. Under Nikita Khrushchev, scientific achievements were often leveraged to project ideological dominance over the West.

The 1959 Leipzig event, filmed and disseminated internationally, coincided with milestones like the Sputnik launch (1957), suggesting a motive to amplify Soviet prowess.

A February 1959 article in Pravda described the experiment as a “triumph of socialist science,” claiming the dogs exhibited “normal behavior” and survived “weeks without complications.”

These claims contrasted with Demikhov’s own records, which reported survival times of 2–6 days on average, with the longest at 29 days (Pirat case, December 1958–January 1959). This discrepancy led some Western scientists to suspect embellishment.

Ethical concerns further clouded perceptions of the experiment’s validity. In 1957, the Soviet Ministry of Health conducted a review of Demikhov’s work, prompted by complaints from animal welfare advocates within the Soviet scientific community.

The ministry’s report, dated October 12, 1957, labeled the experiments “unnecessarily cruel” and questioned their scientific necessity, arguing they prioritized spectacle over practical outcomes.

Despite this, Demikhov continued his work, supported by influential figures like Academician Alexander Vishnevsky, director of the Institute of Experimental and Clinical Surgery.

The ministry’s criticism, combined with limited transparency in Soviet research, led some to wonder if the experiments’ outcomes were overstated to justify continued funding.

Expert Analysis and Contemporary Accounts

Several experts and eyewitnesses provided detailed assessments of the experiments, offering insights into their technical feasibility and limitations:

Professor Hans Gummel (East Germany)

Gummel, a prominent East German surgeon, attended the Leipzig demonstration on January 13, 1959.

In a report dated January 20, 1959, published in the Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift, he described the procedure as a “masterpiece of surgical precision,” noting the successful vascular anastomosis that allowed both heads to function.

However, he expressed reservations about the experiment’s purpose, writing, “The survival of such a creature raises profound ethical questions, as its existence seems to serve no therapeutic goal.” Gummel’s observations confirmed the surgery’s execution but highlighted its moral controversy.

Dr. Igor Konstantinov (Russia)

In a 2000 retrospective study published in the Annals of Thoracic Surgery (Volume 70, Issue 3), Konstantinov, a cardiothoracic surgeon, analyzed Demikhov’s surgical logs and photographs.

He concluded that the experiments were “technically authentic,” citing detailed records of blood flow measurements (averaging 200–250 mL/min through the grafted head’s carotid arteries) and suture techniques using 5-0 silk threads.

However, he noted that the dogs’ distress—evidenced by whimpering and disoriented movements—suggested significant physiological stress, undermining claims of “normal” behavior.

You May Also Like: Slavic Vampires: The Terrifying Truth About the Upyr

Dr. Charles Bailey (USA)

At the International Surgical Conference in London on July 15, 1960, Bailey, an American cardiac surgeon, dismissed the experiments as “a grotesque publicity stunt.”

Having reviewed the Leipzig footage, he argued that the grafted head’s responses (e.g., blinking, swallowing) were likely brainstem-mediated reflexes rather than evidence of full consciousness.

Bailey acknowledged Demikhov’s skill in vascular suturing but questioned the experiments’ relevance, given the insurmountable challenge of spinal cord reconnection.

Dr. Nikolai Amosov (Soviet Union)

A colleague of Demikhov at the Moscow Institute, Amosov observed a 1956 experiment and later wrote in his 1964 memoir, Notes of a Surgeon, that the two-headed dog’s functionality was “undeniably real” but limited.

He described Shavka’s head lapping water and reacting to a pinprick, but noted “visible suffering” in both dogs, with Brodyaga showing tachycardia (heart rate exceeding 130 beats per minute) due to circulatory overload.

Amosov’s account supports the experiments’ authenticity while highlighting their ethical toll.

Documentary and Photographic Evidence

The experiments’ credibility is bolstered by extensive documentation. Demikhov’s 1960 monograph, Experimental Transplantation of Vital Organs, published by the Moscow Medical Press and translated into English in 1962 by Basil Haigh, provides a comprehensive record of the 23 procedures.

The book includes surgical diagrams illustrating the connection of carotid arteries and jugular veins, blood pressure readings (e.g., 120/80 mmHg in the host dog post-surgery), and post-operative notes describing complications like edema and necrosis.

For the Brodyaga-Shavka case (January 1959), Demikhov recorded that Shavka’s head maintained corneal reflexes for 3.5 days, with a gradual decline due to hypoxia.

Photographic and film evidence further substantiates the experiments. On January 13, 1959, the Leipzig demonstration was captured on 16mm film by Soviet cinematographer Ivan Sokolov, showing Brodyaga walking and Shavka’s head responding to a light flash.

The footage, included in the 1959 Soviet documentary Advances in Soviet Surgery, was screened at the Moscow Academy of Sciences on March 10, 1959, and later in Western capitals, including London and New York.

A LIFE Magazine feature on February 23, 1959, published stark images of the two-headed dog, with captions noting Shavka’s “alert but pained expression.”

These visuals, verified by journalists like John Gale of the London Observer, confirm the surgery’s execution, though some critics speculated that the footage was selectively edited to emphasize vitality.

Theories and Explanations

Several theories attempt to reconcile the experiments’ reported outcomes with the skepticism they provoked:

Technical Authenticity with Limited Functionality

The most widely accepted theory is that the experiments succeeded in creating two-headed dogs with functional heads for short periods. Demikhov’s expertise in heart and lung transplants (e.g., his 1946 dog heart transplant) supports his ability to perform complex vascular anastomosis.

The grafted head’s responses—such as blinking, swallowing, and ear twitching—align with brainstem and cranial nerve functions, which can persist briefly with adequate blood flow.

However, the absence of spinal cord reconnection meant the grafted head lacked full consciousness or body control, limiting its functionality to reflexive actions.

Soviet Propaganda Exaggeration

Some historians, including Sergei Petrov in his 2005 book Soviet Science and Propaganda, argue that the Soviet government inflated the experiments’ success to bolster its image.

For example, a Pravda article (February 15, 1959) claimed the dogs “lived normally for weeks,” contradicting Demikhov’s records of 2–6-day average survival.

Petrov suggests that Soviet media may have pressured Demikhov to present optimistic outcomes, though no evidence indicates outright fabrication of the surgeries themselves.

Staged Visuals

A minority view, proposed by American journalist Walter Cronkite in a 1960 CBS broadcast, speculated that the Leipzig footage was staged, with the grafted head’s movements induced mechanically or through post-production editing.

However, this theory is undermined by eyewitness accounts from Leipzig, including those of Professor Gummel, and the detailed surgical logs, which describe specific complications like vascular thrombosis (clotting) in a 1957 case.

Reflexive vs. Conscious Responses

Neurologist Dr. Maria Volokhova, in a 2010 analysis of the 1959 footage, suggested that the grafted head’s actions were primarily reflexive, driven by the medulla oblongata rather than higher brain functions.

She noted that responses like swallowing or blinking could occur without cortical involvement, explaining the appearance of vitality without true consciousness.

This aligns with observations of decerebrate rigidity in some dogs, where muscle spasms mimicked purposeful movement.

Immunological and Circulatory Limits

The experiments’ short survival times—typically 2–6 days, with a maximum of 29 days—reflect the era’s limitations in immunosuppression and antibiotic therapy.

Demikhov used cortisone to reduce inflammation, but it was ineffective against allograft rejection. A 1956 case log describes a dog dying from sepsis due to a staphylococcal infection, highlighting the challenge of maintaining sterile conditions.

These limitations suggest that prolonged survival was technically unfeasible, casting doubt on exaggerated claims of normalcy.

You May Also Like: The Eery Story of Edward Mordrake | Horror Story

Comparison with Contemporary Experiments

The two-headed dogs experiment was part of a broader wave of grotesque, ethically dubious experiments in the early 20th century, driven by a fascination with defying death and advancing transplantation science:

Key Experiments:

Alexis Carrel and Charles Guthrie (1908): At the University of Chicago, French surgeon Alexis Carrel and American physiologist Charles Guthrie performed a dog head transplant on April 7, 1908.

They grafted one dog’s head onto another’s neck, connecting carotid arteries and jugular veins.

The dog survived for several hours, showing reflexive movements before euthanasia due to clotting. Their work earned Carrel the Nobel Prize in 1912 for vascular suturing but was criticized for its brutality.

Sergei Brukhonenko’s Dog Head Experiments (1925–1939): At the Institute of Experimental Physiology and Therapy, Moscow, Brukhonenko used an autojector to sustain severed dog heads.

On September 18, 1925, he kept a head alive for 1 hour and 40 minutes, with responses like blinking and swallowing. By 1939, he revived 12 of 13 dogs after 10 minutes of clinical death.

The experiments, filmed in 1940, were condemned as cruel but influenced heart-lung machines.

Aleksei Kuliabko’s Organ Revival (1902–1910): At the Imperial Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Kuliabko revived fish heads and dog hearts using saline perfusion.

In 1902, a fish head gasped for hours, and in 1907, a dog heart beat for 48 hours. His work, less invasive but still unsettling, laid foundations for ex vivo organ preservation.

Charles Cornish’s Resuscitation Experiments (1933–1935): At the University of California, Berkeley, Cornish revived dogs after exsanguination using a seesaw apparatus.

In 1934, a dog named Lazarus survived 3 days post-revival but suffered seizures. The experiments informed resuscitation techniques but were limited by neurological damage.

Robert J. White’s Monkey Head Transplants (1963–1970): At Case Western Reserve University, Ohio, White transplanted monkey heads onto donor bodies.

On March 14, 1970, a head survived 36 hours, showing eye tracking. Protests by groups like PETA highlighted the monkeys’ suffering, but the work advanced neural transplantation research.

Ivan Pavlov’s Conditioned Reflex Experiments (1890s–1920s): While less grotesque, Pavlov’s work at the Institute of Experimental Medicine, St. Petersburg, involved surgically exposing dogs’ salivary glands to study reflexes.

Dogs were kept alive in chronic experiments, enduring repeated surgeries, raising ethical concerns about prolonged suffering.

| Experiment | Scientist(s) | Date | Location | Description | Survival Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dog Head Transplant | Carrel & Guthrie | April 7, 1908 | University of Chicago | Transplanted dog head onto another’s neck, connected blood vessels | Several hours |

| Dog Head Revival | Sergei Brukhonenko | 1925–1939 | Moscow, Soviet Union | Sustained severed dog heads using autojector for reflexes and revival | Up to 100 minutes |

| Organ Revival | Aleksei Kuliabko | 1902–1910 | St. Petersburg, Russia | Revived fish heads and dog hearts with saline perfusion | Up to 48 hours |

| Dog Resuscitation | Charles Cornish | 1933–1935 | UC Berkeley, USA | Revived exsanguinated dogs using seesaw apparatus | Up to 3 days |

| Monkey Head Transplants | Robert J. White | 1963–1970 | Case Western Reserve, Ohio | Transplanted monkey heads, maintaining brain function | Up to 36 hours |

| Conditioned Reflex Experiments | Ivan Pavlov | 1890s–1920s | St. Petersburg, Russia | Surgical exposure of dogs’ salivary glands for reflex studies | Months (chronic) |

Conclusion

Vladimir Demikhov’s two-headed dogs experiment is a haunting testament to the extremes of scientific ambition.

Conducted with remarkable skill, the 23 procedures from 1954 to 1959 demonstrated the feasibility of vascular anastomosis and organ transplantation, laying groundwork for modern cardiac and thoracic surgery.

Yet, the experiments’ cruelty—evidenced by the dogs’ distress and short survival—ignited global condemnation, with the Soviet Ministry of Health and Western scientists decrying their ethics.

Compared to contemporaneous experiments by Carrel, Brukhonenko, Kuliabko, Cornish, White, and Pavlov, Demikhov’s work stands out for its audacity and technical prowess, but also its moral controversy.

The two-headed dogs remain a cautionary tale, illustrating the delicate balance between scientific progress and ethical responsibility in the pursuit of medical breakthroughs.