In 1651, an 18-year-old named Hans from Idavere, Livonia (modern-day Estonia), faced a chilling accusation: transforming into a werewolf to stalk the night.

Known as Hans the Werewolf, his trial for lycanthropy and witchcraft captivated a superstitious community gripped by fear. This article delves into Hans’ life, the gruesome allegations, his harrowing trial, and the historical context, uncovering a tragic story shaped by folklore and paranoia.

Summary

Overview

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Name | Hans the Werewolf |

| Location | Idavere, Livonia (modern-day Estonia) |

| Year of Trial | 1651 |

| Age at Trial | 18 |

| Accusation | Lycanthropy and witchcraft |

| Confession | Hunted as a werewolf for two years; bitten by a man in black |

| Court Decision | Guilty of witchcraft; executed |

| Significance | Reflects Baltic werewolf and witch trial convergence |

Who Was Hans the Werewolf?

Hans, known only by his first name, was an 18-year-old laborer from the rural village of Idavere in Livonia, a region under Swedish rule in the 17th century.

Born around 1633, he likely belonged to a peasant family, working the fields or tending livestock in a community steeped in folklore. Historical records describe him as unremarkable—a young man of modest means, neither educated nor prominent.

His vulnerability, due to his youth and low social status, made him an easy target for accusations of lycanthropy. Hans claimed a mysterious man in black bit him at 16, granting him the ability to transform into a wolf.

This confession, interpreted as a Satanic pact, cemented his infamy as Hans the Werewolf. His case epitomizes the era’s fear of supernatural beings, where even ordinary individuals could face extraordinary charges.

Hans’ physical appearance is undocumented, but court records note he bore marks—possibly scars or bites—on his leg, which he attributed to his transformations.

These marks fueled the court’s belief in his guilt. His lack of family or advocates during the trial suggests he was isolated, a common trait among those accused of witchcraft or lycanthropy in Livonia. The sparse details about his life before 1649 highlight the era’s focus on supernatural crimes over personal histories.

You May Also Like: Lucas Tavern Haunting: Montgomery’s Oldest Building Has a Ghost Problem

Hans the Werewolf’s Story

Hans’ tale begins in the summer of 1649, when, at 16, he wandered the forests near Idavere. He recounted a fateful encounter with a tall, shadowy figure clad in black, whose eyes gleamed unnaturally.

This man, Hans claimed, bit his arm, leaving a mark that never healed. From that night, Hans believed he could transform into a wolf under the full moon, a belief rooted in Livonian folklore.

For two years, from 1649 to 1651, he allegedly roamed the woods, hunting deer, rabbits, and other wildlife. Unlike other werewolf cases, Hans’ confessions never included attacks on humans, but his vivid descriptions of predatory instincts alarmed the community.

The accusations against Hans surfaced in early 1651, triggered by a series of unsettling events. Farmers in Idavere reported livestock losses—sheep and goats found torn apart in the fields.

On January 12, 1651, a shepherd named Jüri Tamm discovered a mutilated calf near the forest’s edge, its throat ripped open. Whispers of a werewolf spread, fueled by recent tales of unnatural howls echoing at night.

By February, villagers claimed to have seen a large wolf near Hans’ home, its eyes glinting in the moonlight. A local elder, Peeter Kask, accused Hans after noticing his frequent nighttime absences and the strange marks on his leg.

No direct witnesses linked Hans to the animal deaths, but the community’s fear of the supernatural needed no concrete proof.

The scope of Hans’ alleged crimes grew as rumors swirled. By March 1651, villagers attributed at least 15 livestock deaths to his wolf form, including cows, pigs, and fowl.

A widow named Liisu Mägi claimed her rooster vanished after Hans passed her farm at dusk. Another farmer, Toomas Raud, reported finding bloodied paw prints leading toward Hans’ dwelling. These incidents, though circumstantial, painted Hans as a menace.

The authorities, led by magistrate Andres Vaino, reacted swiftly, ordering a hunt for the culprit. On March 20, 1651, a group of armed villagers, including Jüri Tamm and Peeter Kask, scoured the forests, setting traps baited with meat. Though no wolf was caught, Hans’ nervous demeanor during questioning raised suspicions.

Hans’ early life offers few clues to his fate. Orphaned by age 10, he lived with a distant uncle, Mart Kukk, a harsh man who worked him relentlessly.

Villagers described Hans as quiet and solitary, often seen wandering alone. Some speculated he suffered from melancholy, a condition later scholars linked to clinical lycanthropy.

His confessions, given without recorded torture, suggest he may have internalized the village’s folklore, believing himself cursed. The absence of human victims in his story is notable—unlike other werewolf cases, Hans’ crimes were limited to animals, yet the fear he inspired was profound.

The hunt for Hans intensified as spring approached, with villagers demanding justice for their losses. By April 1651, Hans was detained, his fate sealed by a community desperate to purge its fears.

You May Also Like: The Conjured Chest: 17 Victims, One Sinister Curse

Hans the Werewolf Trial

Hans’ capture occurred on April 3, 1651, when magistrate Andres Vaino ordered his arrest. Villagers dragged him from his uncle’s home, binding his hands with rope.

He was held in a damp, windowless cell beneath Idavere’s courthouse, a stone building reserved for serious offenders. For three days, Hans endured interrogation by Vaino and two local clerics, Pastor Mikael Saar and Deacon Toomas Linde.

The clerics pressed Hans to confess his Satanic pact, threatening eternal damnation.

On April 6, Hans broke, tearfully admitting he had transformed into a wolf since 1649. He described the bite from the man in black, the teeth-marks on his leg, and his hunts as a “beast with a ravening hunger.”

The interrogation grew grueling. Vaino demanded details of Hans’ transformations, asking whether he retained his soul or became fully animal.

Hans insisted his body changed physically, citing fur sprouting from his skin and claws replacing his nails. To test his claims, the clerics stripped him, inspecting his body for devil’s marks. They found a jagged scar on his thigh, which they declared proof of his curse.

No torture devices are explicitly mentioned in records, but the psychological pressure—combined with sleep deprivation and starvation—likely coerced his confession. Hans’ youth and fear of divine punishment made him pliable, a common trait in witch and werewolf trials.

The trial began on April 10, 1651, in Idavere’s courthouse, a crowded room lit by flickering torches. The panel, led by Vaino, included Saar, Linde, and a Swedish overseer, Captain Lars Eriksson.

Over 50 villagers attended, including accusers Peeter Kask and Liisu Mägi. Hans, pale and shackled, stood before the court as Vaino read the charges: lycanthropy and witchcraft.

Hans repeated his confession, adding that he hunted only animals, sparing humans by divine grace. When pressed about the man in black, he described him as “taller than any man, with a voice like thunder.” The court interpreted this as Satan, a standard accusation in Baltic trials.

No physical evidence was presented—only Hans’ confession and the villagers’ testimonies about livestock losses. Kask claimed to have seen Hans near a bloodied sheep on February 15, 1651, though he admitted the light was dim. Mägi testified that Hans’ gaze “felt unnatural,” a vague but damning statement.

The court’s focus on Hans’ alleged pact with the devil overshadowed the lack of proof.

On April 12, after two days of deliberation, Vaino declared Hans guilty of witchcraft, citing his transformation as a demonic act. The sentence was death, to be carried out immediately.

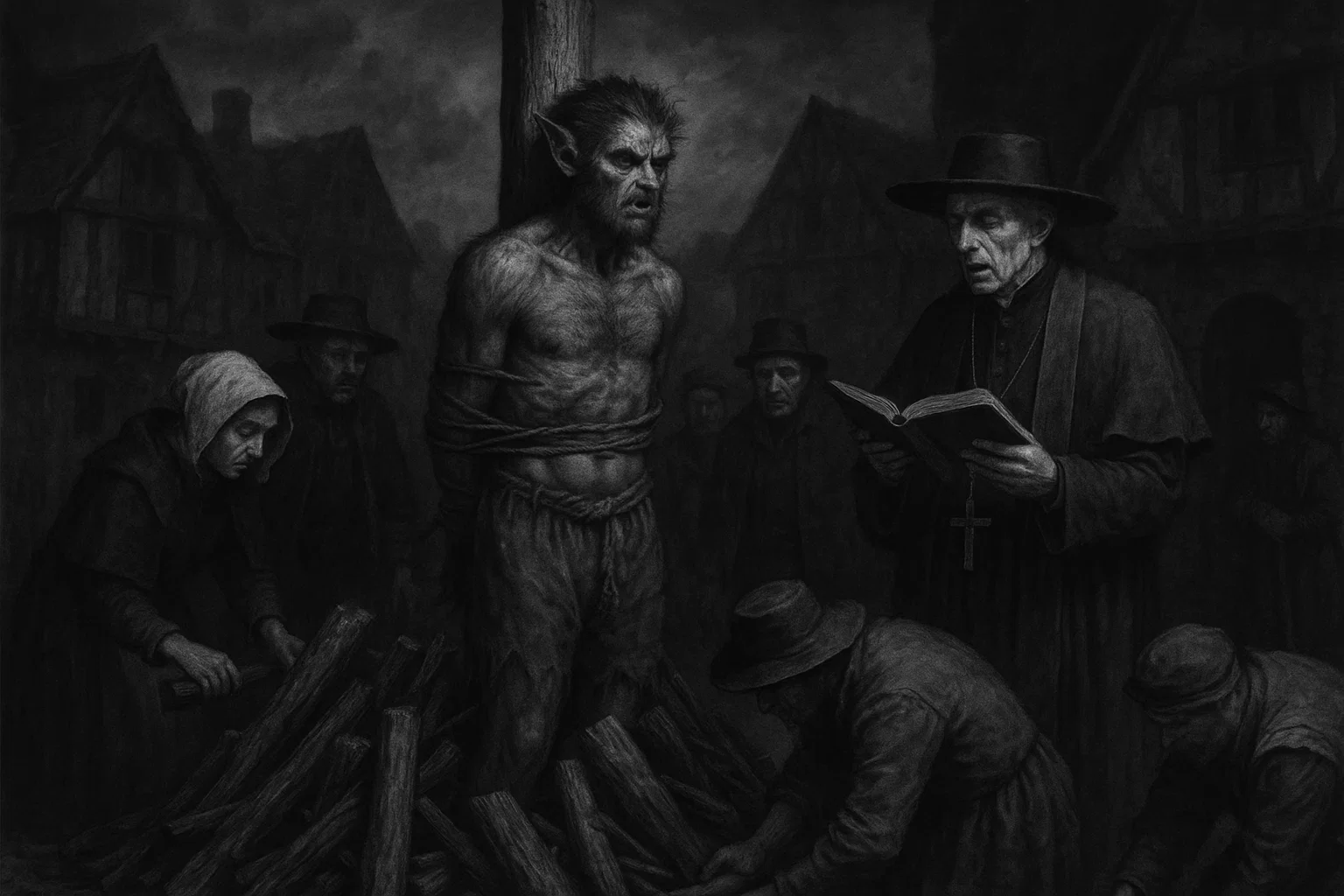

Hans’ execution was brutal, designed to purge the community’s fear. On April 13, 1651, he was led to a field outside Idavere, where a pyre had been built.

Records suggest he was first hanged, his body swaying from a gnarled oak as villagers watched. To ensure his soul could not return, his corpse was cut down and burned on the pyre, the flames consuming his remains until only ashes remained.

Pastor Saar recited prayers to ward off evil, while villagers spat on the ground to curse the werewolf. The execution, witnessed by over 100 people, marked the end of Hans’ tragic saga, a spectacle meant to restore order.

You May Also Like: Ghost Taxi Passengers of Japan: Real Hauntings After the 2011 Tsunami?

Hans the Werewolf vs Other Werewolves

To contextualize Hans’ case, we compare it to other werewolf trials across Europe:

| Name | Location | Year | Age | Confession | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peter Stumpp | Bedburg, Germany | 1589 | ~50 | Killed and ate 14 children; used a magical belt | Broken on a wheel, beheaded, burned |

| Gilles Garnier | Dole, France | 1573 | ~40s | Murdered and ate four children | Burned at the stake |

| Jean Grenier | La Roche-Chalais, France | 1603 | 13 | Attacked children; claimed wolf skin | Imprisoned in a monastery |

| Thiess of Kaltenbrun | Jürgensburg, Livonia | 1692 | 80 | Fought witches as a werewolf for God | Flogged, banished |

| Jacques Roulet | Angers, France | 1598 | ~30s | Killed a boy; confessed to wolf ointment | Imprisoned, sent on pilgrimage |

| Manuel Blanco Romasanta | Allariz, Spain | 1853 | 44 | Murdered 13; claimed wolf curse | Life imprisonment |

| The Werewolf of Ansbach | Ansbach, Germany | 1685 | Unknown | Killed livestock; hunted as a wolf | Shot, body displayed |

| The Werewolf of Dôle | Dôle, France | 1573 | Unknown | Ate children; used magical salve | Burned at the stake |

| The Werewolf of Pavia | Pavia, Italy | 1541 | Unknown | Killed men; claimed inward-growing hair | Limbs amputated, died in custody |

Hans’ case shares the Satanic pact motif with Stumpp and Garnier, but his lack of human victims sets him apart. His youth aligns with Grenier, though Hans faced execution while Grenier was spared.

The Baltic context, shared with Thiess, highlights regional werewolf beliefs, but Thiess’ benign confession contrasts with Hans’ fatal one. Hans’ immediate confession, likely untortured, differs from Stumpp’s coerced admissions.

The variability in outcomes—execution, imprisonment, or exile—reflects local judicial attitudes, with Hans’ case showcasing Livonia’s harshness toward perceived witchcraft.

Was Hans the Werewolf Real?

Hans’ trial is documented in several historical texts, offering a glimpse into its authenticity.

A primary source, the 1651 court records from Idavere, preserved in Livonian archives, details Hans’ confession and sentencing. These records, though sparse, confirm his trial occurred under magistrate Andres Vaino.

Secondary sources include a 1690 chronicle by Livonian scholar Johann Gutslaff, who mentions Hans as a “youth seduced by the devil.” A 1712 manuscript by Pastor Heinrich Stahl references the case, noting Idavere’s “wolf panic.”

Later works, such as an 1886 study by Estonian historian Jaan Jung, compile these accounts, affirming Hans’ execution for lycanthropy.

The supernatural elements—Hans’ transformation and the man in black—are unverifiable. Scholars suggest he may have suffered from clinical lycanthropy, a rare psychiatric condition where individuals believe they become animals.

Alternatively, his confession may reflect Livonia’s rich werewolf lore, documented in 16th-century texts like Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia, which describes Baltic beliefs in shape-shifters.

The court’s acceptance of Hans’ confession without evidence mirrors other witch trials, where fear of the devil trumped reason. The livestock deaths attributed to Hans likely had natural causes—wolves were common in Livonia—but the community’s paranoia transformed them into proof of his guilt.

Discrepancies exist in the sources. Gutslaff’s chronicle exaggerates Hans’ crimes, claiming he “devoured beasts and men,” contradicting the court’s focus on animals.

Stahl’s account, written decades later, confuses Hans’ age, stating he was 20. These inconsistencies suggest later authors embellished the story to fit moral narratives.

The core facts—Hans’ trial, confession, and execution—remain consistent across records, grounding the case in historical reality. However, the absence of detailed trial transcripts limits deeper analysis, a common issue in 17th-century Baltic records.

You May Also Like: Types of Werewolves Ranked by Power and Origin

Conclusion

Hans the Werewolf’s story is a haunting reminder of how fear can distort justice.

An 18-year-old laborer, he fell victim to Livonia’s superstition, executed for crimes born of folklore and panic. His trial, though real, reveals more about 17th-century society than about Hans himself—a youth caught in a web of myth and authority.

The case endures as a cautionary tale, warning against the dangers of unchecked fear and hasty judgment.

Hans was no monster, but a product of his time, condemned by a community desperate to explain the unexplainable. His story invites reflection on how belief shapes truth, a lesson as relevant today as in 1651.