Medusa was one of three Gorgons in Greek mythology, known for her ability to turn those who looked at her into stone.

Born to the sea deities Phorcys and Ceto, she differed from her immortal sisters, Stheno and Euryale, in being mortal. Ancient accounts describe her residing in remote regions near the edge of the known world, where she posed a threat to travelers and heroes alike.

The hero Perseus slew Medusa by severing her head, using divine gifts, including a reflective shield, to avoid her gaze. Her severed head retained its petrifying power and was attached to Athena’s shield—the aegis—serving as a protective emblem.

Early texts portray Medusa as a monstrous figure from birth. However, later versions attribute her transformation to a curse placed on her by Athena following an encounter with Poseidon.

Summary

Key Takeaways

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Names | Medusa, Gorgo; from Greek medousa meaning ‘guardian’ or ‘protectress’ |

| Nature | Monster, daemon |

| Species | Gorgon |

| Appearance | Winged female with snakes for hair, fangs, tusks, bronze claws, and a gaze that petrifies |

| Area | Greece, Libya, near Oceanus; associated with remote islands like Sarpedon |

| Creation | Born monstrous to Phorcys and Ceto; later accounts say cursed by Athena after union with Poseidon in her temple |

| Weaknesses | Mortal unlike her sisters; vulnerable to decapitation without direct gaze; reflective surfaces counter her petrifying eyes |

| First Known | 8th century BCE, Hesiod’s Theogony |

| Myth Origin | Greek cosmology, tied to primordial sea deities and heroic quests |

| Strengths | Petrifying gaze, venomous snake hair, immortality of severed head |

| Associated Creatures | Sisters Stheno and Euryale; siblings Graeae, Echidna; offspring Pegasus and Chrysaor |

| Diet | Not specified in sources; implied predatory nature through petrification of victims |

Who or What Is the Medusa?

Medusa is one of the Gorgons, the three sisters born to the primordial sea gods Phorcys and Ceto. But, unlike her siblings Stheno and Euryale, who were immortal, Medusa alone possessed mortality, making her the target of heroic quests.

Ancient sources depict her as a winged daemon residing at the world’s edge, beyond Oceanus, where she guarded forbidden realms with her terrifying visage.

In core myths, Medusa embodies peril and protection; her image was later adopted as the Gorgoneion to avert evil. Hesiod lists her among monstrous offspring, stressing her role in the genealogy of terrors.

Later Roman adaptations, such as Ovid’s, introduce a tragic element: Medusa as a once-beautiful maiden punished by Athena for Poseidon’s assault in the goddess’s temple, transforming her locks into serpents and her face into a stone-inducing horror.

Medusa’s encounters define her legacy, from her slaying by Perseus—who used her head as a weapon—to her symbolic use on shields and amulets. She links to broader Gorgon lore, where her sisters pursue avengers with cries that inspired Athena’s aulos.

Genealogy

| Relation | Details |

|---|---|

| Grandparents (Paternal) | Pontus (primordial sea) and Gaia (Earth) |

| Grandparents (Maternal) | Pontus (primordial sea) and Gaia (Earth) |

| Father | Phorcys (ancient sea god, son of Pontus and Gaia) |

| Mother | Ceto (sea monster goddess, daughter of Pontus and Gaia) |

| Siblings | Stheno (immortal Gorgon, eldest sister) Euryale (immortal Gorgon, known for far-carrying cry) Graeae (three sisters: Deino, Enyo, Pemphredo; share one eye and one tooth) Echidna (half-woman, half-serpent; mother of monsters) Ladon (serpent-dragon guarding Hesperides’ golden apples) Scylla (originally nymph, later sea monster with dog heads) Thoosa (nymph, mother of Polyphemus by Poseidon) |

| Consort | Poseidon (god of the sea; union in Athena’s temple or prior to curse) |

| Offspring | Pegasus (winged horse, born from neck stump upon decapitation) Chrysaor (giant warrior with golden sword, born from neck stump upon decapitation) |

| Nieces/Nephews (via Echidna) | Orthrus (two-headed dog) Cerberus (three-headed hound of Hades) Hydra (multi-headed serpent of Lerna) Chimera (fire-breathing lion-goat-serpent hybrid) Sphinx (riddle-asking winged lioness) Nemean Lion (invulnerable lion) Caucasian Eagle (tormented Prometheus) |

| Nephew (via Thoosa) | Polyphemus (Cyclops encountered by Odysseus) |

| Nephew (via Graeae) | None directly recorded |

| Aunts/Uncles (via Phorcys & Ceto) | Nereus (Old Man of the Sea) Thaumas (wonder; father of Iris and Harpies) Electra (Oceanid; mother of Iris by Thaumas) Doris (Oceanid; mother of Nereids) |

| Cousins (via Nereus) | Nereids (50 sea nymphs, including Thetis, Amphitrite) |

| Cousins (via Thaumas) | Iris (rainbow messenger goddess) Harpies (storm wind snatchers: Aello, Ocypete, Celaeno) |

| Divine Opponents | Athena (cursed Medusa; received her head for aegis) Perseus (hero who beheaded her; son of Zeus and Danae) |

| Allies of Perseus | Hermes (provided sickle and guidance) Hades (lent helm of darkness) Nymphs of the North (gave winged sandals, kibisis pouch) |

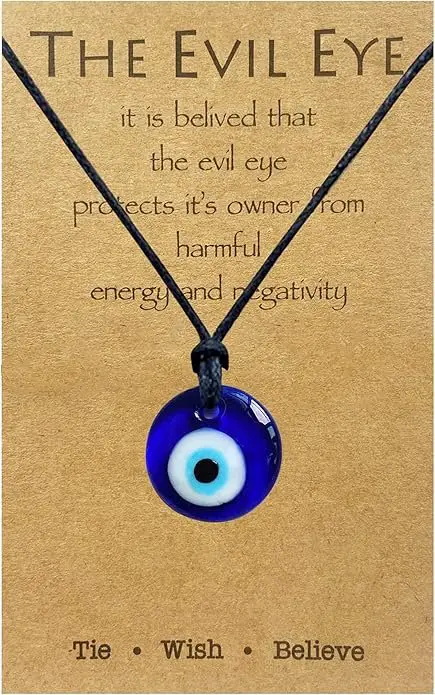

Why Do So Many Successful People Secretly Wear a Little Blue Eye?

Limited time offer: 28% OFF. For thousands of years, the Turkish Evil Eye has quietly guarded wearers from the unseen effects of jealousy and malice. This authentic blue glass amulet on a soft leather cord is the real thing – beautiful, powerful, and ready for you.

Etymology

The name Medusa derives from the Ancient Greek Médousa, which is rooted in the verb medein, meaning “to guard” or “to protect.” This etymology aligns with her role as a fierce sentinel, her image functioning as an apotropaic device to ward off harm.

Early mentions in Hesiod’s Theogony (c. 700 BCE) use the name Medousa without elaborating too much on its meaning or origin, listing her among Phorcys and Ceto’s progeny.

Homer, in the Iliad (c. 8th century BCE), references the “head of the Gorgon” on Athena’s shield, using Gorgo—from gorgos, meaning “grim” or “fierce”—to denote terror. This epithet extends to all Gorgons, implying a shared quality that induces dread. Pindar, in his Pythian Ode 12 (c. 490 BCE), calls her “fair-cheeked Medusa,” blending beauty with menace, a motif that evolves in later art.

By the 5th century BCE, vase paintings and sculptures standardize Medousa alongside Stheno (from sthenos, “strength”) and Euryale (from eury, “wide,” and hale, “sea,” evoking vast oceanic peril).

Aeschylus in Prometheus Bound (c. 460 BCE) describes the “snake-haired Gorgons,” associating them with snake-like horrors. Roman adaptations—like Ovid’s Metamorphoses (c. 8 CE)—retain Medusa while emphasizing transformation, deriving her curse from temple desecration.

Regional variants appear in Libyan accounts by Herodotus (c. 440 BCE), suggesting Berber influences where Medusa ties to solar or protective deities.

Dionysios Skytobrachion (2nd century BCE) places her in North Africa, adapting Medousa to local guardian spirits.

You May Also Like: 15 True Ghost Stories You Shouldn’t Read Alone After Midnight

What Does the Medusa Look Like?

Ancient depictions of Medusa vary across texts and art, stressing her hybrid form as a winged female daemon.

Hesiod omits details, but Homer describes the Gorgoneion as a “thing of fear and horror” with a grim face. By the 7th century BCE, she appears with boar-like tusks, fangs, and a protruding tongue, her eyes glaring wide to evoke paralysis.

Vase paintings from the 6th century BCE portray Medusa with bronze claws, golden wings, and scales covering her body, her head encircled by writhing serpents in place of hair. These snakes hiss and strike, adding to her menacing aura. Early sculptures render her grotesque, with bulging eyes, distorted features, and a wide maw, designed to confront viewers frontally.

In the 5th century BCE, Classical art shifts toward a more humanized form: Medusa as a beautiful yet terrifying woman, her snake-like locks flowing dynamically.

Pindar notes her “fair-cheeked” aspect, influencing Polygnotus’s peaceful sleeping figure in Perseus’s approach. Later Hellenistic works blend allure and horror, with elongated snakes and ethereal wings.

Roman adaptations (like those in Ovid) retain the snakes but stress pre-curse beauty: golden tresses turned foul.

Mythology

Medusa appears in Greek cosmology as a primordial monster, integral to the lineage of sea-born terrors.

Earliest records trace to Homer’s Iliad (c. 8th century BCE), where the Gorgoneion adorns Athena’s aegis as a “head of the dreadful monster Medusa,” evoking instant death for beholders. The Odyssey reiterates this, placing the Gorgon’s head among Hades’s horrors and hinting at her role at the edge of the underworld.

Hesiod’s Theogony (c. 700 BCE) normalizes her genealogy: Medusa, with sisters Stheno and Euryale, offspring of Phorcys and Ceto, residing “beyond glorious Oceanus” near Night and the Hesperides.

Here, Perseus beheads her while she sleeps, birthing Pegasus and Chrysaor from her neck—winged horse and golden-sworded giant—marking her as a generative force amid destruction. Hesiod notes her mortality, distinguishing her from immortal kin.

Aeschylus’s Prometheus Bound (c. 460 BCE) amplifies her threat: the Gorgons as “winged maidens with snaky hair,” loathed by mortals. Their gaze was fatal.

Pindar, in Pythian Ode 12, describes Perseus approaching “the maidens with snaky heads,” slaying “fair-cheeked Medusa,” whose deathly dirge inspires Athena’s aulos, crafted from Euryale’s wail.

Apollodorus’s Library (c. 2nd century BCE) details the quest: Perseus, aided by Hermes and Athena, receives winged sandals, Hades’s helm, and a sickle to sever Medusa’s head at Oceanus’s nymphs. Her blood spawns the Amphisbaena, a sign of her chthonic potency.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses (c. 8 CE) introduces another transformation—Medusa as a beautiful maiden raped by Neptune in Minerva’s temple, cursed with serpents and petrifying eyes.

Libyan variants by Herodotus (c. 440 BCE) and Dionysios Skytobrachion link Medusa to Berber rites, portraying Gorgons as valiant warriors near Lake Tritonis.

Diodorus Siculus (c. 1st century BCE) correlates them with Amazon-like tribes. The same tribes Heracles fought as part of his deeds.

You May Also Like: Futakuchi-onna: The Terrifying Two-Mouthed Woman of Japanese Folklore

Legends

The Quest of Perseus and the Slaying of Medusa

King Polydectes ruled the island of Seriphus and desired to marry Danae, the mother of Perseus. Perseus, a young man and the son of Zeus, stood against this union.

To remove the obstacle, Polydectes devised a plan. They announced a banquet where guests were expected to bring horses as gifts. Perseus, lacking horses, boasted that he could provide any gift, even the head of Medusa, the Gorgon whose gaze turned men to stone. Polydectes seized the opportunity and demanded the head, knowing the task would lead to Perseus’s death.

Perseus set out on the quest, guided by the gods Hermes and Athena. They first directed him to the Graeae, three ancient sisters named Deino, Enyo, and Pemphredo, who shared a single eye and a single tooth.

These sisters knew the location of the Gorgons’ lair. Perseus approached them as they passed the eye back and forth. He snatched the eye when it was in transit, refusing to return it until they revealed the path to the nymphs who guarded certain divine gifts.

The Graeae yielded and told Perseus to seek the nymphs in the far North. There, the nymphs provided him with three items: winged sandals that allowed flight, a cap of darkness from Hades that granted invisibility, and a kibisis, a special pouch to hold the head safely.

Hermes gave Perseus an adamantine sickle curved like a harp, sharp enough to sever the Gorgon’s neck. Athena presented a polished bronze shield that served as a mirror.

Equipped with these tools, Perseus flew across the world to the remote region beyond the river Oceanus, where the Gorgons lived in a cavern near the gardens of the Hesperides. The three sisters—Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa—lay asleep. Stheno and Euryale were immortal, but Medusa alone could be killed.

Perseus donned the cap of darkness, approached using the reflection in the shield to avoid direct eye contact, and positioned himself above Medusa.

With a swift stroke of the sickle, he cut off her head. Blood poured from the stump, and from it sprang the winged horse Pegasus and the giant Chrysaor, who wielded a golden sword; both were offspring of Poseidon from an earlier union with Medusa.

The noise awakened Stheno and Euryale. They rose in fury, their snake hair hissing and their wings beating the air, pursuing the intruder with cries that echoed across the sea.

Perseus, still invisible under the cap and swift on the winged sandals, escaped their grasp. He placed the head in the kibisis and flew back toward Seriphus. Along the way, drops of blood fell to the Libyan desert, giving rise to venomous serpents that plagued the region thereafter.

Upon returning to Seriphus, Perseus found Polydectes still pressing his suit on Danae. In the palace, Perseus unveiled the head, turning Polydectes and his entire court to stone statues that stood as a warning. He then gave the head to Athena, who fixed it upon her aegis.

Ever Walk Into a Room and Instantly Feel Something Watching You?

Millions have used burning sage to force out unwanted energies and ghosts. This concentrated White Sage & Palo Santo spray does the same job in seconds – just a few spritzes instantly lifts stagnation, breaks attachments, and restores peace most people feel immediately.

Medusa’s Curse

In accounts preserved by Roman poets, Medusa was not born monstrous but began life as a mortal woman of exceptional beauty, particularly noted for her luxurious hair. She served as a priestess in the temple of Athena at Athens. Many men sought her favor, drawn by her golden locks that rivaled the goddess’s own attributes.

Poseidon, lord of the sea, lusted after Medusa and pursued her relentlessly. One day, he caught her within the sacred precincts of Athena’s temple. There, between the altars and statues, he forced himself upon her, desecrating the holy site.

Athena, returning to her shrine, discovered the violation. Unable to punish Poseidon—her uncle and a powerful Olympian—she directed her anger at Medusa for allowing the temple to be profaned.

Athena transformed Medusa’s beautiful hair into a mass of writhing, venomous serpents. Her face, once fair, became hideous, with bulging eyes, protruding tongue, and boar-like tusks.

Most dreadfully, Athena cursed her gaze so that any living creature meeting her eyes directly would turn instantly to stone. Medusa, horrified by her reflection, fled in shame and joined her sisters Stheno and Euryale in their distant lair, where she lived in isolation.

The curse extended beyond her form. In some tellings, Medusa wandered the Libyan deserts after the transformation, her gaze creating fields of stone figures—former warriors and travelers frozen in their final moments of terror. One drop of blood from her later beheading produced the two-headed serpent Amphisbaena. In contrast, others gave birth to the vipers of the Sahara.

The Head of Medusa and the Rescue of Andromeda

Perseus, carrying Medusa’s head in the kibisis, continued his journey homeward. He flew over the coast of Ethiopia, ruled by King Cepheus and Queen Cassiopeia. Cassiopeia had boasted that her daughter Andromeda surpassed the Nereids in beauty, offending the sea nymphs.

In retaliation, Poseidon sent a sea monster, Cetus, to ravage the kingdom. An oracle declared that only the sacrifice of Andromeda, chained to a coastal rock, would appease the god.

Perseus arrived as the monster approached, its jaws gaping amid crashing waves. Andromeda, bound and exposed, cried out in despair. Perseus, enamored at first sight, bargained with Cepheus and Cassiopeia: he would slay the beast in exchange for Andromeda’s hand. They agreed.

As Cetus lunged, Perseus soared above on his winged sandals. He drew the head from the pouch and held it toward the monster. The creature’s eyes met Medusa’s gaze, and it solidified into a massive stone reef, still visible in ancient accounts as jagged rocks off the coast. Perseus freed Andromeda, and they wed soon after. Their son Perses became the ancestor of the Persian people.

Later, during a stop in the west, Perseus sought hospitality from the Titan Atlas, who bore the heavens on his shoulders. Atlas, forewarned by an oracle that a son of Zeus would steal his golden apples, refused entry. In response, Perseus produced the head, petrifying Atlas into the mountain range that bears his name, its peaks supporting the sky.

You May Also Like: The Mare: The Nightmare Monster That Crushes Men in Their Sleep

The Founding of Mycenae

After rescuing his mother Danae from Polydectes, Perseus returned the divine gifts to their owners and presented Medusa’s head to Athena. The goddess mounted it at the center of her aegis, creating the Gorgoneion. This protective emblem turned enemy weapons to stone and instilled terror in foes.

Perseus traveled to Argos, his ancestral land, and founded the city of Mycenae. While establishing the site, he used drops of Medusa’s blood.

From the veins on the right side flowed a substance that could raise the dead; Asclepius later employed it in medicine. From the left came poison deadly enough to kill instantly. Perseus strategically planted these drops: the healing blood created medicinal springs around the citadel. At the same time, the poison spawned guardian serpents in the walls.

In Tegea, Perseus gifted a lock of Medusa’s snake hair to Sterope, daughter of Cepheus. This relic, kept in a bronze urn, possessed the power to summon storms and rout invading armies when displayed. Spartan forces once fled upon seeing it.

Athena, mourning the Gorgons’ cries, fashioned the double-reed aulos to mimic Euryale’s lament over Medusa’s death. The instrument’s haunting sound evoked the sisters’ grief, blending sorrow with the martial utility of the Gorgoneion.

The Warrior Queens

In North African traditions recorded by Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus, the Gorgons originated near Lake Tritonis in Libya. Medusa ruled as a warrior queen among a tribe of fierce women akin to Amazons. Her people warred against neighboring tribes and even challenged Heracles during his labor to fetch the golden apples of the Hesperides.

Heracles, traveling through Libya, encountered the Gorgons in their fortified settlement. Medusa, adorned with snake-emblazoned armor, led the defense.

Using the same strategy later employed by Perseus—avoiding direct gaze with a reflective surface—Heracles beheaded her. He carried the head across the desert, where blood drops created the serpents that still inhabited the sands.

Local Berber tribes venerated Medusa as a protective deity, her image carved on shields to avert harm. Temples near the lake displayed stone figures said to be petrified enemies.

The Blood of Medusa and the Birth of Coral

As Perseus flew over the sea with the kibisis, blood seeped through the pouch and dripped into the waters below. Where the drops touched seaweed, they hardened into red coral.

Poseidon, seeing this, decreed that coral would retain Medusa’s petrifying property when alive in the sea but become harmless stone when brought to the surface. Fishermen later used coral branches as amulets, believing they warded off the evil eye due to their Gorgon origin.

In some coastal variants, nymphs gathered the coral. They presented it to Athena, who incorporated fragments into her aegis alongside the head, enhancing its protective aura.

The Stone Fields of Sarpedon and the Petrified Armies

Ancient travelers reported vast plains on the island of Sarpedon, near Cisthene, covered with stone statues of men and beasts in attitudes of flight or combat. These were victims of Medusa and her sisters before Perseus’s intervention.

Armies invading the Gorgons’ territory met their end en masse: one Libyan force, numbering thousands, advanced at dawn only to lock eyes with the waking Gorgons and freeze mid-charge, their weapons raised eternally.

Explorers like Pausanias described finding these fields centuries later, the statues weathered but intact, serving as warnings against hubris. Local inhabitants avoided the area at twilight, when the sisters were said to patrol in search of their lost sibling.

You May Also Like: Huldra: The Beautiful Forest Demon of Scandinavia

Medusa vs Other Monsters

| Monster Name | Origin | Key Traits | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stheno | Greek; daughter of Phorcys and Ceto | Immortal Gorgon, snake-haired, petrifying gaze, winged, strong | None specified; immortality prevents death |

| Euryale | Greek; daughter of Phorcys and Ceto | Immortal Gorgon, snake-haired, petrifying gaze, far-carrying cries, winged | None specified; immortality prevents death |

| Lamia | Greek; Libyan queen turned monster by Hera | Child-devouring daemon, serpentine lower body, prophetic visions, shape-shifting | Removal of eyes allows sleep; vulnerable to heroes like Zeus’s interventions |

| Empusa | Greek; daughter of Hecate | Shape-shifting seductress, bronze leg and donkey leg, blood-drinking, flame-spitting | Iron weapons; mockery or divine aid like Hermes |

| Siren | Greek; sea nymphs | Enchanting song lures sailors to death, bird-women hybrid, prophetic knowledge | Wax earplugs; avoiding their island |

| Scylla | Greek; sea monster from Circe’s spell | Six heads, twelve tentacles, devours sailors, immortal | None; eternal guardian of straits |

| Charybdis | Greek; whirlpool daemon | Swallows and regurgitates sea, tidal destruction | None; cyclical nature unkillable |

| Harpie | Greek; storm winds personified | Bird-women, snatchers of food, foul winds, prophetic | Divine purification; Zetes’s pursuit |

| Sphinx | Greek/Egyptian; Theban guardian | Lion body, woman head, wings, riddle-asking, devours failures | Solving riddle causes suicide |

| Cyclops | Greek; sons of Uranus | One-eyed giants, forge weapons, cannibalistic, immense strength | Blinding the eye; Odysseus’s stake |

| Minotaur | Greek; Cretan labyrinth dweller | Bull-headed man, maze-bound, man-eater | Sword through throat; Theseus’s thread |

Medusa shares snake-like and petrifying traits with the Gorgon sisters Stheno and Euryale, but her mortality sets her apart, enabling her to be defeated heroically, unlike in their immortal forms.

Like Lamia and Empusa, she embodies female peril—seduction twisted to horror—yet Medusa’s gaze offers passive defense, unlike Lamia’s active predation or Empusa’s illusions.

Sea-born kin like Sirens and Scylla/Charybdis evoke inescapable doom. Still, Medusa’s power persists post-mortem as a talisman, contrasting the Sphinx’s intellectual trap or Harpies’ thievery.

Cyclopes and Minotaur parallel brute isolation, vulnerable to cunning, yet Medusa’s curse narrative adds a narrative of victimhood, distinguishing her tragic agency from innate monstrosity.

Powers and Abilities

Medusa wielded formidable abilities rooted in her Gorgon nature, primarily her petrifying gaze that transformed beholders into stone upon direct eye contact.

This power extended to her severed head, retaining potency as a weapon for Perseus and Athena. Her snake hair functioned as living weapons, venomous and prehensile, capable of striking or ensnaring foes.

Winged flight allowed swift evasion, while her immortal sisters’ cries suggest Medusa shared sonic terror, though sources emphasize visual horror.

Blood from her veins held dual properties: the right side life-giving, used by Asclepius for healing; the left poisonous, spawning serpents like the Amphisbaena. As a guardian daemon, Medusa embodied apotropaic force, her image repelling evil even in death.

Her powers and abilities include:

- Petrifying Gaze: Direct eye contact turns living beings to stone; effective on humans, animals, and demigods; persists in severed head.

- Venomous Serpent Hair: Locks of living snakes that bite with lethal poison; controllable for attack or defense.

- Winged Flight: Golden wings enable rapid aerial movement and escape.

- Magical Blood: Right-vein drops heal or revive; left-vein drops create venomous creatures or poison.

- Apotropaic Aura: The presence or image wards off evil, as in talismans like the Gorgoneion.

You May Also Like: The Lernaean Hydra: Greek Myth’s Deadliest Creature

Can You Defeat a Medusa?

Defeating Medusa required exploiting her sole vulnerability: mortality and reliance on direct gaze. Perseus succeeded by avoiding eye contact, using Athena’s mirrored shield to view her reflection while approaching invisibly via Hades’s helm. The adamantine sickle from Hermes ensured clean decapitation during her sleep, preventing retaliation.

Indirect methods countered her petrifying eyes: reflections, shadows, or closed lids neutralized the threat. Post-decapitation, containing the head in a pouch or bag hid its power until needed. Divine aid proved essential—winged sandals for flight, nymphs’ gifts for tools—highlighting mortal limits against her.

Conclusion

Medusa is a complex figure in Greek mythology, representing both fearsome power and a protective presence. Her story takes us on a journey filled with divine influence and heroic action, from her origins to her tragic transformation.

Medusa’s most famous feature, her head, became a symbol known as the Gorgoneion, which illustrates how something terrifying can also serve as a shield of protection. This shift in her image—from a monster to a symbol of guardianship—adds depth to her story and encourages us to consider the heavy costs of power.