Deep within the misty realms of Japanese folklore, where ancient spirits and supernatural entities roam freely, the Ittan-momen emerges as a chilling embodiment of everyday terror. This malevolent yōkai—a sentient, airborne strip of cotton fabric—haunts the twilight skies of Kagoshima Prefecture, transforming innocuous textiles into instruments of suffocation and dread.

Rooted in Shinto animism and tsukumogami traditions, the Ittan-momen exemplifies how ordinary objects can awaken with vengeful intent, preying on lone travelers and unwary souls. Its legend serves as a cautionary narrative, blending the mundane with the macabre, and highlights the cultural fears embedded in Japan’s mythical landscape.

Summary

Overview

| Trait | Details |

|---|---|

| Names | Ittan-momen, Ittan monme, Ittan monmen; etymology from “one tan of cotton,” measuring ~10.6m long, 30cm wide. |

| Nature | Malevolent supernatural yōkai, embodying vengeful spirits in animated objects. |

| Species | Spectral tsukumogami, a class of possessed household items gaining sentience. |

| Appearance | Elongated white cotton cloth, fluttering ethereally, lacking facial features in traditional tales. |

| Area | Primarily Kōyama in Kimotsuki District, Kagoshima Prefecture; sightings in Fukuoka, Tokyo, Shizuoka. |

| Behavior | Nocturnal predator, silently ambushing victims by wrapping and suffocating them. |

| Creation | Awakens as tsukumogami after 100 years of neglect, infused with spiritual essence. |

| Weaknesses | Vulnerable to iron blades for cutting, salt for purification, protective chants. |

| First Known | Documented early 20th century in Ōsumi Kimotsukigun Hōgen Shū by Kunio Yanagita. |

| Myth Origin | Shinto animism and yōkai folklore, linked to Edo-period tsukumogami beliefs. |

| Strengths | Effortless flight, precise wrapping ability, stealth in nocturnal environments. |

| Habitat | Twilight skies near rural paths, shrines like Shijūkusho Jinja in Kimotsuki. |

| Time Active | Predominantly dusk and night, aligning with low visibility for surprise attacks. |

| Associated Creatures | Related tsukumogami such as Kasa-obake, fusuma; parallels with futon kabuse. |

| Protection | Iron tools, salt pouches, ritual incantations to deter spectral encounters. |

What Is Ittan-momen?

The Ittan-momen stands as a quintessential yōkai in Japanese folklore, manifesting as a possessed bolt of white cotton cloth that defies gravity and hunts under the cover of darkness.

Originating from the rural landscapes of Kagoshima Prefecture, this tsukumogami—an animated artifact born from neglected textiles—measures approximately 10.6 meters in length and 30 centimeters in width, embodying the eerie transformation of the ordinary into the ominous. Its predatory instincts drive it to envelop unsuspecting individuals, cutting off their breath in a silent, relentless grip.

Embedded in Shinto traditions, the Ittan-momen symbolizes the latent spirits within everyday items, awakening after a century to exact revenge or mischief. This spectral entity not only terrifies but also reflects cultural admonitions against solitude at night, persisting in modern narratives as a bridge between ancient myths and contemporary imaginations.

Etymology

The term Ittan-momen derives from classical Japanese measurements and materials, where “ittan” signifies “one tan,” a traditional unit equivalent to about 10.6 meters in length and 30 centimeters in width, and “momen” directly translates to “cotton.”

This nomenclature captures the essence of the yōkai as a single bolt of fabric, highlighting its unassuming yet deceptive origins in everyday textile production. Pronunciation varies slightly by region, typically rendered as “it-tan-mo-men,” with emphasis on the elongated syllables to evoke its flowing, ethereal nature. In Kagoshima dialects, it may be softened to “ittan monmen,” reflecting local phonetic nuances.

Historical texts trace the name’s usage to early 20th-century folklore compilations, such as the Ōsumi Kimotsukigun Hōgen Shū, co-authored by folklorist Kunio Yanagita and Nomura Denshi around 1910-1920.

This document formalized the term amid broader yōkai studies, linking it to tsukumogami concepts from the Edo period (1603-1868). The etymology ties into Shinto animism, where objects accumulate kami (spirits) over time, transforming “momen” from mere cloth to a sentient entity. Regional variations include “ittan monme,” incorporating “monme” as a weight unit, though less prevalent outside Kyushu.

Connections to related myths abound, with the name paralleling other cloth-based yōkai like fusuma or futon kabuse, all rooted in household items’ spiritual awakening. Folklorist Komatsu Kazuhiko, in his analyses during the late 20th century, hypothesized links to depictions in the Hyakki Yagyō Emaki, a 15th-century scroll by Tosa Mitsunobu illustrating a parade of spirits, where cloth-like figures appear.

The term’s evolution reflects Japan’s textile heritage, from cotton cultivation in the Meiji era (1868-1912) to symbolic representations in burial customs, where white flags might inspire flying cloth legends. Pronunciation guides in modern yōkai encyclopedias emphasize the rhythmic flow, mirroring the creature’s gliding motion.

Speculative origins suggest influences from Chinese folklore, where animated fabrics appear in tales of possessed silks, but the distinctly Japanese measurement “tan” grounds it in local culture. In oral traditions predating written records, elders in Kimotsuki District used the name to instill fear, evolving from descriptive phrases like “flying cotton bolt” to the standardized Ittan-momen.

This linguistic journey underscores the yōkai‘s role in moral storytelling, warning against neglect or hubris toward possessions. By the Showa era (1926-1989), popularized through manga, the name gained phonetic consistency, solidifying its place in national mythology.

You May Also Like: Japanese Horror: The Terrifying Ghost of Aka Manto

What Does the Ittan-momen Look Like?

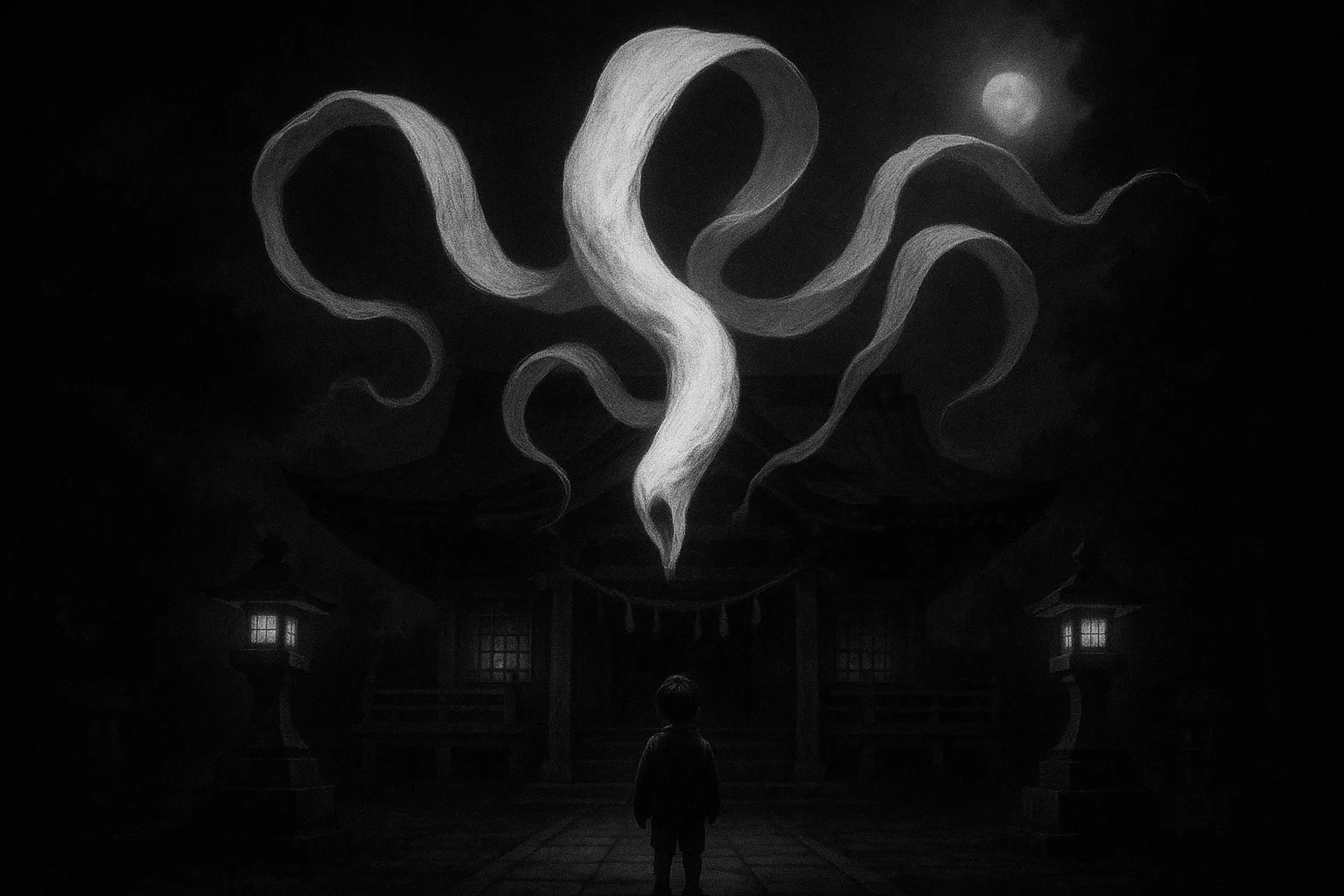

The Ittan-momen manifests as an elongated strip of pristine white cotton, stretching approximately 10.6 meters long and 30 centimeters wide, resembling a discarded bolt from a kimono weaver’s loom. Its surface appears smooth and unblemished, with a subtle sheen under moonlight that enhances its ghostly allure, often described as fluttering like a banner caught in an invisible breeze.

In traditional folklore from Kagoshima, it lacks any anthropomorphic traits—no eyes, arms, or facial expressions—emphasizing its impersonal, object-like terror that blends seamlessly into the night sky.

Regional variations add layers to its depiction; in Kyushu tales, the cloth might exhibit faint, ethereal patterns reminiscent of burial shrouds, evoking connections to ancestral spirits. Some accounts from Fukuoka describe it as semi-transparent, allowing stars to glimmer through its fabric, heightening the sense of otherworldliness.

Textural details in legends portray it as deceptively soft yet unyielding, with a cool, clammy feel upon contact, akin to damp linen left in the dew. Sounds accompany its approach—a faint rustling like wind through leaves—or a subtle whoosh as it descends, building dread before the strike.

In contrast, modern interpretations, influenced by artists like Shigeru Mizuki in the 1960s, anthropomorphize the Ittan-momen with two piercing eyes and grasping arms, transforming it into a more characterful entity for visual media. However, purists argue these additions deviate from authentic folklore, where its featureless form underscores the fear of the unknown.

Sensory folklore from Shizuoka sightings includes a musty scent of aged cotton, mingling with the night’s chill, further immersing victims in its supernatural presence. This minimalist aesthetic, rooted in tsukumogami lore, amplifies its menace, proving that simplicity can harbor profound horror.

Mythology

The Ittan-momen‘s mythology is deeply intertwined with Japan’s Shinto animism, where all objects harbor potential spirits, or kami, that awaken after prolonged neglect. As a tsukumogami, it represents the awakening of discarded cotton bolts, typically after 100 years, embodying resentment toward human indifference.

This concept traces back to the Heian period (794-1185), when Shinto texts like the Engishiki (927 CE) alluded to spiritual essences in tools and fabrics, setting the stage for yōkai evolution. In Kagoshima’s rural context, the Ittan-momen likely emerged during the Edo period (1603-1868), amid agricultural shifts and cotton farming booms, symbolizing fears of crop failures or economic hardships.

Historical events, such as the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877 in Kagoshima, may have amplified its lore, with tales of flying cloths interpreted as omens of unrest or vengeful souls from battlefields. Pre-literary beliefs in animism, predating written records, suggest origins in shamanistic practices where shamans invoked spirits in textiles for protection or curses.

The creature’s airborne nature parallels natural phenomena like gliding musasabi (Japanese giant flying squirrels), documented in naturalist texts from the 18th century, which might have inspired sightings of ethereal fabrics darting through forests.

Connections to other beings enrich its narrative; it shares kinship with fusuma from Sado Island, a cloth yōkai that smothers pedestrians, and futon kabuse from Aichi, a flying bedding that suffocates sleepers. These parallels, noted in yōkai compilations like Toriyama Sekien’s Gazu Hyakki Yagyō (1776), illustrate a broader theme of household rebellion. The Ittan-momen’s evolution reflects societal changes: during the Meiji Restoration (1868), industrialization displaced traditional crafts, fueling stories of animated relics protesting modernity.

Cultural significance extends to moral lessons, cautioning against wastefulness and solitude, especially in isolated villages where banditry posed real threats. Folklorist Kunio Yanagita’s early 20th-century works, including field studies in 1910s Kimotsuki, documented its role in child-rearing, using fear to enforce curfews during busy farming seasons.

Influences from plagues, like the 19th-century cholera outbreaks, might link suffocation motifs to respiratory illnesses, blending myth with historical trauma.

In the Taisho era (1912-1926), urbanization spread legends to cities like Tokyo, where 1920s sightings at train stations symbolized the clash between rural traditions and urban life. Post-World War II, the Ittan-momen gained prominence through Shigeru Mizuki’s manga in the 1960s, humanizing it for new generations while preserving its core menace. This adaptation mirrors Japan’s post-war identity crisis, where ancient folklore comforted amid rapid change.

The creature’s ties to burial customs—white cotton flags raised during funerals in Kagoshima—suggest a deathly association, possibly linking it to obake (ghosts) or yūrei (spirits). Figures like Tosa Mitsunobu, in his 15th-century Hyakki Yagyō Emaki, depicted similar cloth entities in yōkai parades, hypothesizing prehistoric roots. Komatsu Kazuhiko’s 1980s analyses further connected it to ecological fears, like windstorms carrying debris, anthropomorphized into predators.

Overall, the Ittan-momen’s mythology evolves from animistic roots to a symbol of cultural resilience, influencing art, literature, and festivals. In Sakaiminato, Tottori, it topped yōkai popularity polls in the 2000s, underscoring its enduring appeal.

Ittan-momen in Folklore:

- Heian Period (794-1185): Early animistic beliefs in object spirits lay foundational concepts for tsukumogami.

- Muromachi Period (1336-1573): Hyakki Yagyō Emaki by Tosa Mitsunobu depicts cloth-like yōkai, potential precursors.

- Edo Period (1603-1868): Oral traditions in Kagoshima solidify legends amid cotton trade growth.

- Meiji Era (1868-1912): Industrial changes inspire tales of vengeful artifacts; Yanagita begins documentation.

- Taisho Era (1912-1926): Urban migrations spread stories to Tokyo and beyond.

- Showa Era (1926-1989): Mizuki Shigeru’s works popularize it nationally.

- Heisei Era (1989-2019): Modern sightings in Fukuoka, Shizuoka; kamishibai revivals in 2007 by Takenoi Satoshi.

- Reiwa Era (2019-Present): Continued presence in anime, games, and tourism.

You May Also Like: Yuki-onna Legends: Tales of Love, Death, and Betrayal

Legends

The Twilight Assault on the Weary Traveler

In the dimming light of a Kagoshima evening around 1910, a lone samurai named Hiroshi trudged along a narrow path in Kōyama, his mind heavy with the day’s labors. The air grew thick with an unnatural chill as a whisper of wind stirred the leaves, but no breeze followed.

Suddenly, a pristine white cloth descended from the shadowed canopy, coiling around his neck with serpentine precision. Gasping for breath, Hiroshi’s hands clawed at the fabric, which tightened like a living noose, its cool texture betraying no warmth of life. In a flash of desperation, he drew his wakizashi, the short sword slicing through the cloth with a metallic ring.

The entity recoiled, vanishing into the night, leaving only droplets of ethereal blood on his blade—a spectral residue that locals whispered was the yōkai’s essence. This encounter, passed down through generations in Kimotsuki District, served as a stark reminder of the perils lurking in solitude, urging villagers to travel in pairs during harvest seasons when fields demanded late hours.

Years later, elders recounted how Hiroshi’s tale inspired protective rituals, with families etching wards on doorposts to avert similar fates. The legend’s details, rooted in oral histories collected by Kunio Yanagita, emphasize the Ittan-momen’s stealth, appearing without warning to exploit vulnerability.

Unlike mere fabric, it moved with intent, wrapping not just the body but ensnaring the spirit in fear. This story’s evolution reflects community bonds, transforming a personal horror into a collective caution, woven into festivals where performers reenact the slash to honor resilience against the supernatural.

The Haunting Vigil at Shijūkusho Jinja

Nestled amid the ancient cedars of Shijūkusho Jinja in Kimotsuki, a sacred site dating to the 15th century, whispers of the Ittan-momen echoed through the 1920s as a guardian of twilight boundaries. Children like young Miko, playing near the shrine’s torii gates as dusk fell, often heard parents’ stern warnings: the last in line would feel the cloth’s embrace.

One fateful evening in 1925, Miko lagged behind her siblings, giggling at fireflies, when a silent white shroud materialized from the shrine’s eaves. It fluttered gracefully at first, like a forgotten prayer flag, before lunging to envelop her face, muffling her cries in its suffocating folds.

Her brother, alert to the lore, brandished a small iron knife—a family heirloom blessed at the shrine—and slashed at the entity, which dissolved into mist with a faint, mournful sigh. Miko’s survival sparked renewed reverence for the shrine, where priests attributed the attack to disrespect toward ancestral spirits.

This legend, distinct in its ties to sacred spaces, contrasts with open-path ambushes, suggesting the Ittan-momen as a divine enforcer. Regional variations add that offerings of salt at the altar could appease it, blending fear with ritualistic piety. The tale’s structure, building from innocence to climax, mirrors shrine purification ceremonies, reinforcing cultural harmony with the supernatural.

You May Also Like: Futakuchi-onna: The Terrifying Two-Mouthed Woman of Japanese Folklore

The Spectral Pursuit Along the Shinkansen Tracks

Amid the roaring advance of modernity in the 1980s, a Fukuoka businessman named Kenji boarded the Shinkansen, gazing out at the blurring Kyushu landscape as night encroached. Around 1985, near the bullet train’s high-speed corridor, a peculiar white streak paralleled the window, matching the train’s velocity without effort.

Kenji, initially dismissing it as a reflection, watched in growing unease as the cloth-like form undulated, its edges rippling like waves on a stormy sea. Witnesses later described it hovering at eye level, attempting to press against the glass as if seeking entry, its presence evoking a chill that fogged the panes.

The entity persisted for miles, vanishing only when the train entered a tunnel, leaving passengers murmuring of ancient curses adapting to steel and speed. This modern legend, documented by yōkai enthusiast Bintarō Yamaguchi in his 1980s journals, highlights the Ittan-momen’s adaptability, shifting from rural haunts to urban intrusions.

Unlike traditional tales of personal encounters, this one involves collective sightings, fostering debates on whether industrialization awakens dormant spirits. The story’s pacing, accelerating with the train, symbolizes Japan’s rapid progress clashing with timeless folklore, inspiring commuter talismans like iron keychains.

The Ethereal Encounter in Tokyo’s Urban Shadows

In the bustling yet isolating streets of 1990s Tokyo, a woman named Aiko walked her dog near Higashi-Kōenji Station one foggy evening in 1992. The city lights cast elongated shadows, and amid the hum of traffic, a translucent sheet materialized overhead, drifting lazily before descending with purposeful grace.

Aiko felt its cool edges brush her skin, wrapping around her shoulders in a gentle yet insistent hold, tightening as she struggled. Her dog’s frantic barks alerted passersby, who scattered salt from a nearby vendor, causing the cloth to unravel and flee skyward.

This urban variant, differing from rural ambushes by incorporating city elements like streetlights and crowds, underscores the yōkai’s migration with human populations. Details from eyewitness reports emphasize its adaptability, perhaps feeding on the anonymity of city life. The legend serves as a bridge between eras, reminding modern Japanese of ancestral warnings in concrete jungles.

The Child’s Narrow Escape in Shizuoka Fields

During a 2000s summer in Shizuoka Prefecture, a group of elementary school children explored rice paddies at twilight in 2005, their laughter echoing across the fields. Young Haruto, straggling behind, spotted a shimmering white form hovering above, resembling a lost kite.

It swooped down, encircling his torso and lifting him slightly off the ground, his friends’ screams piercing the air. One child, recalling classroom folklore lessons, hurled a handful of dirt mixed with salt, disrupting the entity’s grip and allowing Haruto to break free.

This tale, unique in its child-centric focus and agricultural setting, parallels shrine warnings but adds levitation elements, heightening the abduction fear. It reflects educational integrations of yōkai lore, preserving cultural heritage through youthful narratives.

The Burial Flag’s Vengeful Flight

In Kagoshima’s burial customs of the late 19th century, around 1890, a mourner named Sato witnessed a white cotton flag from a recent funeral detach and soar unnaturally during a procession in Kimotsuki.

As night fell, it targeted him, wrapping around his head in a suffocating veil redolent of earth and incense. Sato bit through the fabric—a method borrowed from related fusuma legends—causing it to disintegrate.

This legend ties directly to death rituals, positing the Ittan-momen as a manifestation of unresolved grief, distinct in its ceremonial origins and sensory details like incense scents.

You May Also Like: Who Is the Noppera-bo? The Eerie Legend of Japan’s Faceless Ghost

Ittan-momen vs Other Monsters

| Monster Name | Origin | Key Traits | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kasa-obake | Japan | One-legged umbrella, hops mischievously, animated object | Fire, dismantling |

| Nurikabe | Japan | Invisible blocking wall, impedes travel, spectral barrier | Tapping base, dawn light |

| Yuki-onna | Japan | Snow woman, freezes prey with breath, seductive spirit | Heat sources, sunlight |

| Kappa | Japan | River imp, drowns swimmers, water-filled head dish | Dehydrating dish, cucumbers |

| Tengu | Japan | Mountain goblin, wind control, winged humanoid | Humble gestures, exorcisms |

| Banshee | Ireland | Wailing harbinger, foretells death, ethereal female | Inescapable omen, no direct |

| Strigoi | Romania | Vampiric undead, blood-draining, shape-shifter | Garlic, stakes, decapitation |

| Pontianak | Malaysia | Vengeful ghost, lures with cries, female apparition | Nails, sharp metals |

| La Llorona | Mexico | Weeping specter, abducts children, watery haunt | Crosses, holy water |

| Rusalka | Slavic | Water nymph, drowns victims, seductive allure | Iron chains, fire |

| Chupacabra | Latin America | Livestock drainer, spiky back, nocturnal beast | Bullets, traps |

| Wendigo | Native American | Cannibal spirit, insatiable hunger, emaciated form | Fire, silver weapons |

The Ittan-momen aligns closely with fellow tsukumogami like Kasa-obake, sharing object animation and mischievous origins, yet distinguishes itself through lethal intent rather than playful antics. Its suffocation method echoes the drowning tactics of Kappa or Rusalka, but its aerial domain sets it apart from water-bound entities.

Compared to seductive spirits like Yuki-onna or Pontianak, the Ittan-momen’s featureless form lacks allure, relying on stealth over deception. Weaknesses such as iron and salt recur across cultures, similar to Strigoi or Rusalka, indicating shared folk remedies against the supernatural.

Unlike omen-bringers like Banshee or La Llorona, it actively harms without prophecy, emphasizing its role as a direct predator in Japanese folklore.

Powers and Abilities

The Ittan-momen wields a formidable array of supernatural prowess, chief among them its seamless flight, allowing it to navigate the night skies with effortless agility, evading detection until the moment of attack.

This aerial dominance, devoid of wings or propulsion, stems from its spiritual essence, enabling silent descents upon prey. Complementing this is its suffocation capability, where the cloth conforms to victims’ forms, sealing airways in an unyielding embrace that folklore describes as inescapable without intervention.

Examples abound in tales, such as the samurai’s encounter where the entity coiled with precision, adapting to struggles. Unlike multifaceted yōkai like Tengu with elemental control, the Ittan-momen’s abilities are streamlined for lethality, including minor levitation in some variants, hoisting victims skyward.

Its stealth—blending into darkness or mimicking harmless fabrics—amplifies terror, a trait shared with spectral beings but uniquely tied to its textile origins.

You May Also Like: Hyakume: The Hundred-Eyed Yokai That Watches from the Shadows

Can You Defeat Ittan-momen?

Confronting the Ittan-momen demands adherence to time-honored folklore remedies, primarily wielding iron blades to sever its fabric form, as demonstrated in the samurai’s legend where a wakizashi slash dispersed the entity.

Iron’s purifying properties, rooted in Shinto metallurgy beliefs from the Yayoi period (300 BCE-300 CE), disrupt spiritual bonds, making tools like knives or scissors essential for travelers in Kagoshima. Regional variations in Kyushu incorporate blessed iron from local smiths, etched with protective kanji for enhanced efficacy.

Salt emerges as another cornerstone defense, scattered to form barriers or hurled directly, leveraging its cleansing role in rituals like those at Shijūkusho Jinja. Tales from the 1920s describe children using salt pouches, a practice akin to warding off oni (demons) during Setsubun festivals. Herbs such as mugwort or garlic, though less documented for Ittan-momen, parallel remedies for similar tsukumogami, bundled in amulets to repel ethereal presences.

Ritual chants, intoned in rhythmic patterns, invoke kami protection; phrases like “Kami no hikari yo, akumu wo harae” (Divine light, dispel the nightmare) echo through oral traditions, disrupting the yōkai’s approach.

Comparisons to Kappa‘s cucumber offerings or Yuki-onna‘s warmth vulnerabilities highlight thematic consistencies, but Ittan-momen’s material nature favors physical disruption over symbolic bribes. In Tokyo adaptations, modern talismans combine ancient woods like hinoki cedar with salt, carved into pendants for urban commuters.

Preventive measures include group travel, as solitary targets invite attacks, and shrine offerings to appease lurking spirits. For invulnerability claims in some lore, persistent rituals underscore human ingenuity against the supernatural, blending practicality with spirituality.

Conclusion

The Ittan-momen encapsulates the profound interplay between the ordinary and the extraordinary in Japanese folklore, serving as a timeless emblem of how neglected artifacts can harbor malevolent forces.

Its spectral flights and suffocating grasps not only evoke primal fears but also mirror societal values of respect for possessions and community vigilance. Through centuries of evolution, from Edo-period origins to modern reinterpretations, it remains a vital thread in the fabric of yōkai narratives.

This entity’s cultural resonance extends beyond terror, inspiring artistic expressions and moral reflections that bridge generations. As Japan navigates contemporary challenges, the Ittan-momen endures as a reminder of the unseen spirits that shape human experience.

In an era of rapid change, its legend invites contemplation on the balance between tradition and innovation, ensuring its place in the pantheon of supernatural lore.