The Satyr is a monster from ancient Greek mythology, characterized as a male nature spirit or lesser deity associated with the wilderness, fertility, and revelry. They are perhaps best known for their part-human, part-animal appearance, combining a human body with goat-like features such as horns, tails, and legs.

Satyrs are linked to the god Dionysus, the deity of wine, ecstasy, and theater. They formed part of his ecstatic retinue, or thíasos, and are often depicted in art and literature pursuing Nymphs and indulging in wine, music, and unrestrained sexuality.

In Roman mythology, they were often equated with the Fauns. However, distinctions sometimes existed, with Fauns typically having a gentler nature and stronger ties to the agricultural land rather than the wild forests.

Summary

Key Takeaways

| Attribute | Details |

| Names | Satyr (Sátyros); Faunus (Roman equivalent); Tityros (pastoral name) |

| Nature | Lesser deity/Spirit/Daimon (specifically nature spirit) |

| Species | Humanoid, Beast (hybrid) |

| Appearance | Part human, part goat; possessed of horns, tail, pointed ears, and sometimes goat legs, with a permanent erection (phallic) |

| Area | Ancient Greece, Italy, forests, mountains, woodlands, and fields |

| Creation | Born from gods (often Hermês or Silenus) or the earth; inherent spirits of the wild |

| Weaknesses | Avoidance of wine/feasting; can be tricked or captured by heroes or gods |

| First Known | 8th century BCE; earliest certain depictions are in Geometric and Archaic Greek art |

| Myth Origin | Ancient Greek mythology, associated with the cult of Dionysus |

| Strengths | Immense physical strength; swiftness; compelling music; resistance to intoxication |

| Associated Creatures | Nymphs, Maenads, Sileni (elderly Satyrs), Pan |

| Habitat | Wild, untamed forests, groves, mountains, caves |

Who or What Is Satyr?

The Satyr is a quintessential figure in Greek mythology, representing the untamed, primal aspects of nature and human desire.4 They are essentially fertility spirits tied directly to the vitality of the natural world—forests, mountains, and pastoral lands. Their nature is one of uninhibited freedom and instinctive passion, embodying the id in contrast to the civilized nature of humans.

In the pantheon, Satyrs occupied a position below the major Olympian deities, acting as a chorus of wildness. They are perhaps most frequently portrayed as companions to Dionysus, forming his thíasos alongside the frenzied Maenads. This association highlights their role as the embodiment of ecstasy and liberation found in wine, music, and dance.

Satyrs were generally considered mortal, unlike the Olympian gods, but their lifespans were often lengthy, spanning centuries. They were viewed as neither inherently good nor evil, but rather as capricious and mischievous entities whose actions were dictated by their powerful, simple, and often aggressive desires.

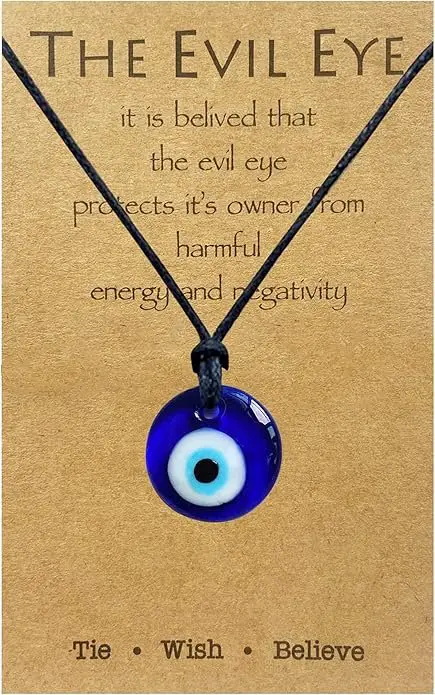

Why Do So Many Successful People Secretly Wear a Little Blue Eye?

Limited time offer: 28% OFF. For thousands of years, the Turkish Evil Eye has quietly guarded wearers from the unseen effects of jealousy and malice. This authentic blue glass amulet on a soft leather cord is the real thing – beautiful, powerful, and ready for you.

Genealogy

The lineage of the Satyrs is often vague or varied in classical sources, befitting their status as spirits of the wild rather than organized deities. They are frequently described as a race of beings indigenous to the earth, rather than strictly the offspring of a single divine couple.

| Relation | Name |

| Potential Fathers | Hermês (Hermes is cited in some traditions as the father of the Satyrs) |

| Potential Mothers | Iphthime (mentioned as a mother of Satyrs in some sources); Nymphs |

| Ancestral Figure | Silenus (Sileinós), often considered the oldest, wisest, and leader of the Satyrs; sometimes called their father |

| Key Associations | Dionysus (They are his constant companions, forming his thíasos) |

| Equivalent Race | Fauns (The Roman equivalent, often merged with Satyrs in later mythology) |

Etymology

The term Satyr derives from the Ancient Greek word Sátyros (Σαˊτυρoς). The etymological roots of the name are uncertain, and various theories exist, none of which is definitively proven. One long-standing but unverified hypothesis attempts to connect the name to a word root meaning to sow or to be full, perhaps alluding to their fertility-focused nature and sexual appetite.

In later Greek and Roman literature, the Satyrs were often conflated with or considered closely related to the Sileni (Sileinós), who were generally depicted as elderly, frequently drunken, and sometimes wiser Satyrs. The chief of this group was Silenus, the foster-father and companion of Dionysus.

In Roman mythology, the Satyrs were frequently equated with the Fauns (Faunī), spirits of the wild closely related to the god Faunus. The name Faunus may relate to the Latin word favere, meaning to be kindly disposed to, suggesting a potentially gentler nature than the Greek Satyrs.

However, in art and popular culture, the visual and behavioral differences between the two entities largely diminished over time, leading to their near interchangeability. The name Tityros (Tıˊtυρoς), often associated with the pastoral poetry of Theocritus and Virgil, was also occasionally used as an alternative name for a Satyr.

The persistence of the Sátyros name through millennia highlights their key role as the embodiment of primitive masculinity and the untamed life force in classical antiquity.

You May Also Like: Ittan-momen: The Flying Cloth Yokai That Strangles Victims

What Does the Satyr Look Like?

The classical description of the Satyr underwent changes over the centuries. In Archaic Greek art, Satyrs were often depicted as fully human from the waist up, with horses’ tails and ears. Their features were frequently crude, flat-nosed, and bearded, emphasizing their bestial nature.

By the Classical and Hellenistic periods, the Satyr’s depiction began to evolve into the more familiar goat-like form. They retained the human-like torso and arms but were typically given goat horns, shaggy hair, and a goat’s tail. Crucially, the lower half often depicted cloven hooves and goat legs.

They were frequently shown in a state of permanent, conspicuous erection (phallophoria), a direct visual symbol of their preoccupation with fertility and unrestrained desire. They were also often shown with wreaths of ivy or vine leaves, and carrying a thyrsus (a fennel staff) or a kántharos (drinking cup), underscoring their close association with Dionysian rituals and wine.

The elder Satyrs, or Sileni, were often bald, obese, and highly intoxicated, frequently needing to be supported or riding a donkey.

Mythology

The earliest certain appearances of the Satyr are found in Archaic Greek art, particularly on vases from the 6th century BCE. Here, they are already established as attendants of Dionysus, participating in his wild festivals (Dionysia).

Their origin story is not singular and definitive; they are generally considered an indigenous race of nature spirits co-existing with Nymphs and other forest beings.

Their mythological role centers on ecstasy and fertility. Satyrs were believed to inhabit the most remote and uncivilized parts of the Greek world—mountain slopes, deep forests, and secluded glades.

They were considered dangerous, particularly to women and young men who wandered alone, due to their hypersexuality and propensity for mischief. They were often associated with the panic of the wilderness—a terror that could strike travelers suddenly—and with their close relative, the god Pan.

Satyrs are prominently featured in satyr plays, a genre of ancient Greek theatre that followed a trilogy of tragedies. These plays, characterized by vulgarity, buffoonery, and explicit sexual humor, starred a chorus of Satyrs led by Silenus.

This artistic tradition firmly cemented their image as both comic relief and as the embodiment of uncivilized human desire. Although they lacked the profound narrative arcs of the main gods and heroes, their presence in mythology was vital as a natural force, representing the necessary chaos and wildness that contrasted with the order and structure of human civilization.

Ever Walk Into a Room and Instantly Feel Something Watching You?

Millions have used burning sage to force out unwanted energies and ghosts. This concentrated White Sage & Palo Santo spray does the same job in seconds – just a few spritzes instantly lifts stagnation, breaks attachments, and restores peace most people feel immediately.

Legends

The Capture of King Midas and Silenus

One of the most widely referenced legends involving a prominent Satyr figure is that of Silenus and King Midas. The story appears in various sources, including the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

The narrative recounts that Silenus, the oldest and wisest of the Satyrs and the foster-father of Dionysus, once wandered off from the Dionysian thíasos while they were passing through Phrygia. Intoxicated with wine and his age, he became lost and subsequently fell asleep in the rose garden of King Midas, who was famed for his wealth and for his devotion to Dionysus.

Midas’s servants discovered the sleeping Satyr and, recognizing him, bound him with garlands of flowers. They then led him to their King. King Midas, having been initiated into the mysteries of Dionysus by the legendary musician Orpheus, received the captive Satyr with great honor.

Midas held a great feast for Silenus that lasted ten days and ten nights, during which the Satyr’s wild, intoxicating tales and wise, yet pessimistic, philosophical discourses on the nature of life and death were listened to.

After the conclusion of the feast, Midas personally returned Silenus safely to the god Dionysus. In gratitude for the King’s piety and hospitality, Dionysus offered Midas a single wish of his choosing.

Midas, known for his greed, wished that everything he touched would turn to gold. This wish was granted, leading to the well-known tragedy where Midas turned his own food, drink, and even his beloved daughter into gold, forcing him later to beg Dionysus to remove the dangerous gift.

You May Also Like: Koschei the Deathless: The Skeleton Sorcerer Who Couldn’t Die

The Musical Contest of Marsyas

The Satyr Marsyas is central to a tragic myth that highlights the Satyr’s natural connection to music and the dangers of hubris in challenging a god. Marsyas was a skilled musician who is said to have picked up the aulos, a double-reed wind instrument, after the goddess Athena had thrown it away. Athena discarded the instrument because playing it contorted her face and made her look ugly.

Marsyas, after mastering the aulos, became puffed up with pride in his musical ability. His arrogance grew to the point where he dared to challenge the god Apollo to a musical contest.

Apollo, the god of music, the arts, and poetry, accepted the challenge. However, it was understood that the winner could inflict any penalty he wished upon the loser. Apollo played his instrument, the lyre, and Marsyas played the aulos.

The contest was fierce, and sources often differ on the judge, sometimes naming the Muses or King Midas. In most accounts, Apollo was declared the victor. Some say Apollo won by singing while playing the lyre, a feat Marsyas could not match with the wind instrument.

Having won, Apollo, in his divine wrath over the Satyr’s presumption, chose a brutal punishment: he flayed Marsyas alive. He then nailed the Satyr’s skin to a pine tree near a cave in Phrygia.

The Nymphs, Satyrs, Fauns, and Shepherds who mourned Marsyas’s death wept so profusely that their tears formed the river Marsyas in Phrygia.

Satyrs and Nymphs

Satyrs are almost perpetually depicted in pursuit of Nymphs (Númphai), the various female spirits of nature.35 The Nymphs, who personify the sweet, delicate, and fertile aspects of the wild—rivers, trees, springs, and glades—are the chief objects of the Satyr’s unrestrained sexual desire.

In countless pieces of Greek vase painting and sculpture, Satyrs are shown chasing, grabbing, or attempting to embrace Nymphs. This common theme is not a single, defined story but a mythological trope that symbolizes the dynamic between the untamed, lustful spirit of the Satyr and the ephemeral, often fearful, yet ultimately resilient spirit of the Nymph.

Sometimes, the Nymphs successfully evade their pursuers, as is often the case with the Nymphs of Artemis, the goddess of the hunt and chastity. In other instances, a sexual encounter is implied or explicitly depicted, which highlights the Satyr’s function as a symbol of primal fertility necessary for the renewal of nature.

These interactions were often characterized by a mix of mischief, fear, violence, and ecstatic abandon, embodying the wilderness’s chaotic vitality. The persistent theme also served as a cautionary tale for young women regarding the dangers lurking in isolated, wild places.

You May Also Like: Sleipnir: The Terrifying Eight-Legged Horse of Norse Mythology

Satyr vs Other Monsters

| Monster Name | Origin | Key Traits | Weaknesses |

| Faun | Roman Mythology | Roman counterpart, often gentler, more rural, fully goat-legged, less overtly bestial | Can be outsmarted; associated with human sacrifice in some early cults |

| Pan | Greek Mythology | Major god of the wild, shepherds, and flocks; fully goat-legged, pipes of Pan, causes ‘panic’ | Challenging his music; associated with a single death at the hands of Typhon in some accounts |

| Centaur | Greek Mythology | Half-human, half-horse (four legs), associated with wildness, sometimes wisdom (Chiron) | Violence and intoxication often turn them against each other; can be killed with conventional weapons |

| Lestrygonians | Greek Mythology | Race of giant, cannibalistic men; monstrous in size and appetite | Conventional warfare; heroes like Odysseus can escape their attack |

| Sileni | Greek Mythology | Elder, often drunken Satyrs; sometimes wiser and fatter; associated with divination | Intoxication (though resistant), capture when sleeping, can be forced to share wisdom |

| Gorgons | Greek Mythology | Female monster with snakes for hair, capable of turning men to stone with a gaze | Mirror shield/reflective surface, decapitation by a hero (Perseus) |

| Incubus | European Folklore | Male demon that lies upon sleepers, particularly women, to have sexual intercourse | Religious rituals, exorcism, specific charms or prayers |

| Puck (or Robin Goodfellow) | English Folklore | Mischievous, shapeshifting fairy or sprite, associated with trickery and night time | Iron, true belief, sometimes specific rituals or banishment |

| Cyclops | Greek Mythology | Gigantic race of one-eyed, strong, often cannibalistic creatures | Blinding their single eye (e.g., Odysseus), conventional weapons |

The Satyr stands out from similar entities due to its unique fusion of goat and human characteristics and its specific, constant association with the cult of Dionysus.

Like the Faun (its near-identical Roman counterpart) and Pan (its divine kin), the Satyr is primarily a fertility spirit and a spirit of the untamed wild. All three embody the primal, uncivilized aspects of existence. However, Pan is a god who inspires panic, while Satyrs are more often associated with ecstasy, revelry, and uncontrolled lust.

Unlike the Centaur, the Satyr’s bestial half is that of a goat, not a horse, and the Satyr is physically less formidable than a Centaur (who is half-man and half-horse). The Satyr’s nature is more mischievous and lustful than purely destructive (like the Lestrygonians) or terrifying (like the Gorgons).

The Incubus shares the theme of sexual aggression. Still, it is a purely demonic, nocturnal entity. In contrast, the Satyr is a physical, forest-dwelling spirit of the day and night. The key differentiator for the Satyr is its constant role in Dionysian thíasos, making it a figure of celebratory, wine-fueled wildness above all else.

You May Also Like: The Lernaean Hydra: Greek Myth’s Deadliest Creature

Powers and Abilities

The Satyr’s powers and abilities are almost entirely focused on its primal nature, physical strength, and connection to the wilderness and the Dionysian cult. They are not known for complex magic, but rather for raw, instinctual capabilities.

Their powers include:

- Superhuman Physicality: Satyrs possess great physical strength and endurance, enabling them to traverse difficult terrain with ease, wrestle with forest creatures, and engage in prolonged uninhibited revelry.

- Swiftness: They are known to be extremely fast and agile runners, making them difficult to capture in the deep woods. Their agility is crucial for both hunting and pursuing Nymphs.

- Musical Talent: Satyrs are inherently gifted in music, often playing the aulos (reed pipe) or syrinx (Pan-pipes). Their music is compelling and ecstatic, capable of driving listeners into a frenzy or simply providing the soundtrack for their revels.

- Resistance to Intoxication: Due to their constant association with Dionysus and wine, Satyrs are often depicted as having a remarkable capacity to consume alcohol without succumbing to the ill effects that would incapacitate a mortal.

- Superhuman Strength: The ability to lift heavy objects, overcome human opponents, and travel long distances without rest.

- Natural Agility/Swiftness: Exceptional speed and grace, allowing quick movement through dense forests and rocky terrain.

- Musical Compulsion: The ability to play instruments (primarily the aulos and syrinx) with an intoxicating skill that can influence and excite listeners.

- High Tolerance for Alcohol: An inherent resistance to the intoxicating effects of wine, allowing them to remain active and functional during prolonged revelry.

Can You Defeat a Satyr?

Defeating or dealing with a Satyr generally requires a combination of cleverness, entrapment, and capitalizing on their simple desires. As physical beings, Satyrs can be killed by conventional means, such as weaponry. Still, their superhuman strength and swiftness make direct confrontation difficult for a mortal.

The most famous method of dealing with a Satyrs, particularly the wise Silenus, involves entrapment using their vice: wine. The story of King Midas demonstrates this: the Satyr was lured by the promise of wine or simply drank until he collapsed, allowing him to be bound and captured while he slept.

A simple yet effective strategy is to leave out wine in a prominent location to lure them into a state of unconsciousness or preoccupation.

Another form of defense is avoidance. Satyrs tend to avoid overly civilized or ordered spaces, preferring the wild, so staying on well-worn roads and out of deep, untamed forests or remote mountain caves is a protective measure.

For Nymphs, the best defense was often simply outrunning or hiding from their relentless pursuit. In mythology, heroic figures occasionally encounter and kill a Satyr, but this is usually an incidental act, not the primary focus, suggesting they are not considered a major threat that requires a specialized hero or weapon to overcome.

You May Also Like: Mormo: The Terrifying Child-Snatching Monster of Ancient Greece

Conclusion

The Satyr is a fundamental, albeit lesser, figure in Greek mythology, acting as the corporeal embodiment of physis—the untamed, natural world—in stark contrast to the ordered world of human nomos (law and custom).

Their hybrid appearance, combining human and goat elements, visually signifies the tension between human reason and animal instinct. This tension is played out in their perpetual pursuit of Nymphs, their constant indulgence in wine, and their roles as the riotous, ecstatic attendants of Dionysus.

Far from being mere monsters, Satyrs function as a cultural mirror, reflecting the primitive desires and uninhibited masculinity that human society attempts to civilize. Their presence in art and dramatic forms, such as the satyr play, provided a necessary, sometimes vulgar, release from the rigors of tragic thought.