In Greek mythology, the Sphinx is a powerful monster sent to the city of Thebes to impose punishment through riddles and violence. This creature combines elements of human and animal forms, posing a challenge that demands intellectual resolution from passersby. Failure to answer correctly results in death by strangulation and consumption.

Records place the Sphinx within earlier monstrous lineages, often linked to figures such as Typhon and Echidna. Her presence ties into broader themes of divine retribution against human communities, with her defeat marking a shift in local governance and the community’s fate.

Summary

Key Takeaways

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Names | Sphinx, Phix; Greek Σφίγξ (Sphínx), from σφίγγειν (sphíngein) meaning “to squeeze” or “to strangle” |

| Nature | Monster, demon of destruction and misfortune |

| Species | Hybrid: humanoid head with leonine body |

| Appearance | Woman’s head and breasts, lion’s body and tail, eagle’s wings; sometimes serpent’s tail |

| Area | Thebes, Boeotia, Greece; originated from Ethiopia or Africa |

| Creation | Offspring of Typhon and Echidna, or Orthrus and Chimera |

| Weaknesses | Correctly solving her riddle leads to self-destruction |

| First Known | 8th century BCE, Hesiod’s Theogony |

| Myth Origin | Adapted from Egyptian and Near Eastern guardian figures into Greek punitive monster lore |

| Strengths | Flight, superhuman strength, riddle-posing that enforces lethal consequences |

| Associated Creatures | Chimera, Nemean Lion, Cerberus, Lernaean Hydra, Orthrus |

| Habitat | Rocky outcrops and roads near Thebes |

| Diet | Human victims who fail the riddle |

Who or What Is Sphinx?

The Sphinx appears in Greek accounts as a female monster tasked with afflicting the city of Thebes through a specific riddle. She perches on a high rock outside the city gates, intercepting travelers and residents alike. Those unable to provide the correct response face immediate death, typically by being seized and devoured.

Her form integrates traits from multiple species, reflecting a composite design common to Greek monstrous entities. The head and upper torso resemble a woman, while the lower body adopts a muscular lion build, complete with paws and a tail.

Wings enable aerial movement, allowing her to spot and pursue quarry efficiently. Some variants include a serpent tail for added menace. This hybrid structure highlights her position between human intellect—embodied in the riddle—and animal ferocity.

The Sphinx’s activities extend beyond random predation; she systematically isolates Thebes, preventing entry or exit until her conditions are met. Her riddle probes fundamental aspects of human existence, demanding recognition of life’s stages.

Success against her elevates the victor, often granting royal authority as a reward from the beleaguered populace.

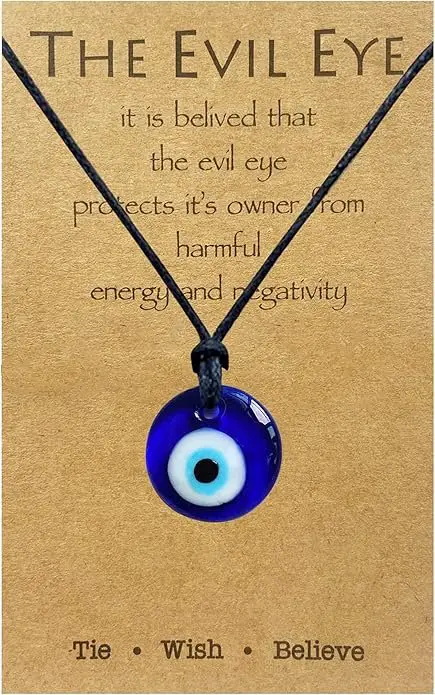

Why Do So Many Successful People Secretly Wear a Little Blue Eye?

Limited time offer: 28% OFF. For thousands of years, the Turkish Evil Eye has quietly guarded wearers from the unseen effects of jealousy and malice. This authentic blue glass amulet on a soft leather cord is the real thing – beautiful, powerful, and ready for you.

Genealogy

| Relative | Details |

|---|---|

| Grandparents (Paternal) | Typhon (father of Echidna): monstrous serpentine giant, hundred dragon heads, storm-bringer; Gaia (mother of Typhon): primordial Earth goddess |

| Grandparents (Maternal) | Phorcys (father of Echidna): ancient sea god, son of Pontus and Gaia; Ceto (mother of Echidna): sea monster, daughter of Pontus and Gaia |

| Parents (Primary) | Echidna: half-woman, half-serpent; “Mother of Monsters”; Typhon: father of winds and chaos |

| Parents (Alternate) | Chimera: fire-breathing lion-goat-serpent hybrid; Orthrus: two-headed hound, brother of Cerberus |

| Siblings (via Echidna & Typhon) | Cerberus: three-headed hound guarding the Underworld; Lernaean Hydra: multi-headed regenerative serpent; Orthrus: two-headed dog guarding Geryon’s cattle; Nemean Lion: invulnerable golden-furred lion; Ladon: hundred-headed dragon guarding the Hesperides’ golden apples; Caucasian Eagle: bird that tormented Prometheus; Crommyonian Sow: giant pig slain by Theseus; Colchian Dragon: guardian of the Golden Fleece |

| Siblings (via Chimera & Orthrus) | Nemean Lion: invulnerable lion; possibly shared with Echidna-Typhon lineage |

| Offspring | None recorded; the Sphinx is childless in all sources |

| Aunts/Uncles (via Echidna) | Gorgons (Stheno, Euryale, Medusa): snake-haired sisters; Graeae (Deino, Enyo, Pemphredo): gray witches sharing one eye and tooth; Scylla: sea monster with dog heads; Sirens: bird-women singers |

| Aunts/Uncles (via Typhon) | None directly named; Typhon’s siblings include other primordial giants |

| Cousins (via Gorgons) | Pegasus and Chrysaor: born from Medusa’s severed neck |

| Extended Kin (via Orthrus) | Geryon: three-bodied giant guarded by Orthrus |

Etymology

The term Sphinx derives from the Greek Σφίγξ (Sphínx), a word linked by ancient grammarians to the verb σφίγγειν (sphíngein), which translates to “to squeeze,” “to bind,” or “to strangle.” This connection aligns with the creature’s method of killing victims by throttling them before consumption, emphasizing her role as a strangler in Theban lore.

However, scholars note that this etymology remains uncertain and possibly folk-derived, as it does not directly tie into the riddle aspect or broader symbolic functions.

Alternative names include Phix, used in some early texts (such as Hesiod’s works), potentially drawn from regional dialects or phonetic adaptations.

The name’s application to the Greek monster likely occurred after contact with Egyptian sculptures, where similar figures lacked a specific designation. Still, it was later labeled Sphinx by Greek observers. This borrowing reflects Mediterranean cultural exchanges around the 8th century BCE, when Greek traders and settlers encountered Levantine and Egyptian art forms.

Historical records trace the term’s evolution through Hesiod’s Theogony, where the Sphinx appears without explicit etymological explanation, focusing instead on her monstrous parentage. Later authors like Apollodorus and Pausanias reinforce the strangling connotation, describing her assaults in detail.

By the Classical period, the name standardized in literature and art, appearing on vases and reliefs as a winged hybrid. In non-Greek contexts, equivalents appear: the Egyptian shesepankh (“living image”) for statues, or Assyrian lamassu descriptors, but these predate and influence the Greek form without direct linguistic ties.

Folk traditions in Boeotia associated the name with local topography, such as the Phicium mountain near Thebes, where the Sphinx supposedly perched. This geographic link suggests a secondary layer of meaning, blending the creature’s identity with the landscape of her depredations.

Over time, the term extended metaphorically in Greek usage to denote enigmatic or puzzling figures, detached from the original monster. In comparative mythology, parallels appear in Persian manticore vocabulary (martyahvārah, “man-eater”), highlighting shared Indo-European roots for hybrid predators, though without the riddle element.

You May Also Like: Morax: The Bull-Headed Demon of Hell

What Does the Sphinx Look Like?

Depictions of the Sphinx in Greek sources consistently portray a female figure with a human head and breasts, transitioning to a lion’s body for the torso and limbs.

The paws end in sharp claws suited for gripping prey during attacks. Eagle wings attach to the shoulders, providing flight capability, and are often shown folded or extended in artistic renderings. A tail completes the leonine rear, sometimes extended into a serpent form for heightened threat.

Early vase paintings from the 7th century BCE depict her seated upright on rocky perches, adorned with a headdress or diadem to accentuate her feminine aspect.

Mythology

The Sphinx enters Greek records as a foreign import, adapted from Egyptian and Near Eastern guardian motifs into a punitive demon. The earliest literary mention occurs in Hesiod’s Theogony, around 700 BCE, where she is listed among the chthonic offspring of primordial monsters.

Here, she appears as the daughter of Orthrus—a two-headed hound—and Chimera, or alternatively Typhon and Echidna, placing her in a lineage of hybrid threats to order. This genealogy ties her to pre-Olympian chaos and to siblings, including the Nemean Lion and Cerberus.

Artistic evidence predates Hesiod, with sphinx motifs on Minoan and Mycenaean artifacts from 1600 BCE, showing winged forms on seals and pottery. These likely arrived via trade from the Levant, where Assyrian lamassu combined human heads with bull or lion bodies.

By the Geometric period (8th century BCE), Greek potters depicted her as a standalone figure, often flanking scenes or adorning graves as apotropaic wards against evil.

In Theban mythology, the Sphinx manifests as divine retribution, sent by Hera, Ares, or Dionysus for offenses like Laius’s crimes or Cadmus’s foundational sins.

Pausanias (2nd century CE) recounts her arrival from Ethiopia, emphasizing exotic origins. She establishes a blockade at Thebes, her riddle sourced from the Muses, enforcing isolation until Oedipus intervenes. This narrative, elaborated in Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex (429 BCE), transforms her from abstract peril to narrative catalyst.

Later Hellenistic texts, like Apollodorus’s Bibliotheca (2nd century BCE), detail her physical assault: strangling victims mid-air before devouring them.

Pliny the Elder (1st century CE) extends her habitat to the Ethiopian wilds, describing brown-haired variants. These accounts blend natural history with myth, portraying her as a real hazard in peripheral regions.

Ever Walk Into a Room and Instantly Feel Something Watching You?

Millions have used burning sage to force out unwanted energies and ghosts. This concentrated White Sage & Palo Santo spray does the same job in seconds – just a few spritzes instantly lifts stagnation, breaks attachments, and restores peace most people feel immediately.

Legends

The Plague of Thebes

The city of Thebes was suffering because its leaders had angered the gods. Laius, the king, had done something terrible by stealing Chrysippus, the son of Pelops, which led to a curse on his family.

After Laius was killed by an unknown attacker, his wife Jocasta took over the rule alongside her brother Creon. Enraged by these events, the goddess Hera sent a creature called the Sphinx from her home in Ethiopia to seek revenge.

The Sphinx settled on a mountain overlooking Thebes, where she could see everyone trying to enter the city. With her wings spread out, she would stop anyone who approached, asking them a riddle: “What creature walks on four legs in the morning, two at noon, and three in the evening?”

Many travelers, farmers, and messengers attempted to answer her, but those who failed faced deadly consequences; she would attack and destroy them without mercy. Young men in the city were particularly affected, as their parents kept them indoors to avoid the Sphinx.

As fear spread, crops began to die, trade stopped, and the city gates stood empty. Creon sought guidance from the oracles and learned that the city could be saved only by solving the Sphinx’s riddle.

He promised that anyone who could defeat the creature would earn the throne and Jocasta’s hand in marriage. Many brave souls tried: warriors, clever thinkers, even noblemen from Thebes —but all met the same tragic fate, their remains scattered beneath the mountain.

The Sphinx grew bolder, coming down at night to snatch victims right out of their fields, her laughter echoing through the darkness. Weeks turned into months, and the city’s population began to dwindle.

Priests offered sacrifices—bulls, goats, and incense—but she paid no attention, only wanting to see minds struggle with her riddle. Creon’s guards kept watch around the city, but nobody dared to approach the Sphinx.

You May Also Like: Alkonost: The Bird-Woman Monster That Sings You Into Trance

In this time of great fear, Thebes waited desperately for someone to save them, surrounded by the growing number of grave markers.

Oedipus Solves the Riddle

Oedipus was a man who had been forced to leave his home in Corinth after a prophecy warned that he would kill his father and marry his mother.

Lost and unaware of his true heritage—he was actually the son of King Laius and Queen Jocasta—he wandered through the region of Boeotia. With nothing but a staff to guide him, he moved towards the city of Thebes.

At a crossroads near Potniae, Oedipus encountered a royal chariot that wouldn’t let him pass. In a chaotic struggle, he ended up killing the chariot’s driver and, unknown to him, his father, King Laius.

When he finally reached Thebes, he found the city in distress—farms were deserted, women were crying, and smoke rose from burning graves. The people of Thebes explained that they were being tormented by a creature called the Sphinx, a beast that had the body of a lion and the head of a woman.

Determined to help, Oedipus, who was skilled in riddles, decided to confront her. Though Creon, a royal messenger, warned him that others had failed before him, Oedipus was undeterred, motivated by the possibility of becoming king and freeing the city from its suffering.

Ascending the mountain where the Sphinx perched, he found her waiting, looking both fierce and cunning. After a moment of silence, she asked him a riddle: “What walks on four legs in the morning, on two legs at noon, and on three legs in the evening?”

Oedipus thought for a moment and realized the answer was “Man.” As a baby, a person crawls on hands and knees; as an adult, he walks on two legs; and in old age, he uses a cane for support.

Once Oedipus gave the correct answer, the Sphinx was defeated. Different versions of the story tell how she either tried to attack him but was killed instead, or jumped from a cliff in embarrassment, falling to her death.

Word quickly spread that Oedipus had saved Thebes. The citizens appeared from hiding, celebrating him as their hero. Creon gave up the throne, and Jocasta, in her mourning, married Oedipus, the man who unknowingly killed her husband.

Celebrations began, the city reopened for trade, and the land was replanted. Oedipus was a good ruler at first, and they had four children: two sons named Eteocles and Polyneices, and two daughters named Ismene and Antigone.

But even in this moment of success, the prophecy hung over him, hinting at a dark secret about his past that was waiting to come to light.

Sphinx vs Other Monsters

| Monster Name | Origin | Key Traits | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chimera | Greek | Lion-goat-serpent hybrid, fire-breathing | Bellerophon’s spear and Pegasus flight |

| Nemean Lion | Greek | Invulnerable golden-furred lion | Strangulation in cave hide |

| Cerberus | Greek | Three-headed guard dog of underworld | Lulled by drugged honey cake |

| Lernaean Hydra | Greek | Multi-headed serpent, regenerative | Cauterized neck stumps, golden sword |

| Manticore | Persian | Human head, lion body, scorpion tail, man-eater | Arrow to vulnerable underbelly |

| Griffin | Greek/Persian | Eagle-lion hybrid, treasure guardian | Distraction by shiny objects |

| Medusa | Greek | Snake-haired gorgon, petrifying gaze | Decapitation by mirrored shield |

| Siren | Greek | Bird-women singers, luring to doom | Wax earplugs, mast binding |

| Minotaur | Greek | Bull-headed man, labyrinth dweller | Sword in ritual sacrifice |

| Cyclops | Greek | One-eyed giant, forge worker | Blinding with heated stake |

| Gorgon | Greek | Petrifying sisters, winged serpents | Heroic beheading |

| Harpie | Greek | Wind spirits, bird-women snatchers | Chained to rock by divine command |

The Sphinx shares hybrid compositions and predatory roles with creatures like the Chimera and Manticore, emphasizing composite forms that blend intelligence with savagery.

Similar to the Nemean Lion and Hydra, she embodies localized threats overcome by heroic intellect or force, often tied to divine curses on cities.

Differences arise in her riddle mechanism, unique among man-eaters like the Minotaur or Cyclops, which rely on physical mazes or brute strength rather than mental trials.

Winged variants (like Griffins and Harpies) parallel her mobility but lack the feminine, interrogative persona of Sirens or Medusa.

You May Also Like: The Mare: The Nightmare Monster That Crushes Men in Their Sleep

Powers and Abilities

The Sphinx is a remarkable creature, combining the strength of a lion with the ability to fly like an eagle. This unique mix allows her to hunt effectively, whether on the ground or from the air, making her a powerful presence around Thebes, where she can capture her victims from a distance or while soaring through the sky.

But what truly sets the Sphinx apart is her skill in crafting riddles. She uses her intelligence to create puzzles that challenge people’s understanding of life, trapping them in a mental game before she attacks.

Myths say she has a special insight that helps her choose questions that reveal human weaknesses, and most people who try to answer her riddles fail, becoming her next meal.

Her voice is captivating, drawing in those who hear her and preventing them from escaping. As a creature from the underworld, she can briefly withstand attacks from humans, making her tough to defeat.

Here are some of her abilities:

- Flight: She can fly high, using her eagle wings to scout for prey and dive down when needed.

- Superhuman Strength: With the power of a lion, she can overpower and tear apart large animals or humans.

- Riddle Challenges: She poses tricky questions, and those who fail to solve them face dire consequences.

- Crushing Grip: Her strong forepaws can hold onto her prey tightly, much like a powerful squeeze.

- Keen Senses: From high above, she can sense travelers approaching from miles away.

- All-Consuming Hunger: When her victims fail her challenges, she swallows them whole, biding her time for the next one.

- Prophetic Insight: She has a unique ability to draw inspiration for her riddles from deeper truths about life.

Can You Defeat a Sphinx?

Defeating the Sphinx hinges on intellectual resolution rather than combat prowess. The primary method is to answer her riddle accurately. Oedipus’s success demonstrates that preparation through prior riddle exposure aids this approach.

Physical confrontation proves futile against her strength and flight; earlier challengers armed with spears or bows fell to aerial grapples. Some accounts suggest that post-riddle strikes hasten the demise, but the enigma remains central.

Preventive measures include avoiding her territory—rerouting travel from Theban roads—or consulting seers for hints. Divine favor, like Apollo’s guidance, bolsters chances, though curses bind her inescapably to the challenge.

You May Also Like: Was the Kraken Real? The Origins of a Norse Horror Legend

Conclusion

The Sphinx stands as a powerful symbol in Greek mythology, representing the struggle between wildness and intelligence, as well as order and chaos.

By blending stories from Egypt with local tales, the Sphinx transforms from a simple guardian into a complex figure that shapes destiny. Throughout her trials in Thebes, she reveals human weaknesses, with her famous riddle serving as a deep reflection on the journey of life and death.

Beyond just myths, the Sphinx has influenced art and philosophy, embodying mysteries that challenge us to confront them. Although many have defeated her, the lessons of her story continue to resonate in tragedy, reminding us that a hard-won victory can also bring unforeseen dangers.