The Piasa Bird is a legendary monster in Native American mythology. This cryptid is historically linked to a massive rock painting (or pictograph) on the limestone bluffs of the Mississippi River near present-day Alton, Illinois.

While the name suggests a terrifying, man-eating aerial cryptid, the Piasa Bird’s true identity is complex, drawing on a blend of ancient Indigenous spiritual iconography and dramatic 19th-century American folklore.

Summary

Overview

| Attribute | Details |

| Name | Piasa Bird |

| Aliases | Piasa; Piyesiw (potential Cree/Thunderbird link); The Bird That Devours Men; Flying Dragon (1825 sketch name) |

| Threat Level | Predatory and Man-Eating (legendary/19th century); Spiritual Danger (original Indigenous context) |

| Habitat | Limestone bluffs along the Mississippi River, specifically near the Illinois River confluence, Alton, Illinois |

| Physical Traits | Varying descriptions: calf-sized, deer horns, man-face, red eyes, scaled body, long fish/serpentine tail (1673 account); or a huge flying chimera with large wings (modern depictions) |

| Reported Sightings | Primarily documentations of the original pictograph, not a living creature, in the Alton, IL area. |

| First Documented Sighting | 1673 (Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet) |

| Species Classification | Mythological/Spiritual Entity (Mississippian culture); Unknown (Cryptozoological speculation) |

| Type | Chimeric/Airborne (Modern Legend); Hybrid/Chthonic/Terrestrial (Original Pictograph) |

| Behavior & Traits | Man-eater (fiction); Elusive (modern cryptid context); Spiritual guardian/warning near dangerous waters |

| Evidence | Eyewitness accounts (of the painted images); 17th-century French drawings; 19th-century sketches; Modern mural re-creations |

| Possible Explanations | Depiction of the Indigenous deity Underwater Panther (Mishipeshu); Hoax/Fabrication (1836 narrative by John Russell) |

| Status | Cultural Landmark; Debunked as biological entity; Subject of ongoing ethnohistorical study. |

Who or What Is the Piasa Bird?

The Piasa Bird is generally understood by the public as a monstrous flying raptor. Still, its identity is essentially split between two disparate traditions.

The creature’s name, Piasa, is often traced to the Algonquian Illiniwek language, where it translates to “A Bird That Devours Men”. The definition reinforces the image of a deadly avian predator.

However, the oldest and most reliable account of the Piasa is not a tale of a creature, but a record of a painting. In 1673, when French explorers Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet documented the image on the bluffs, the creature they described was not a bird. It was a hybrid monster, covered in scales and possessing a long, winding tail.

The idea of the Piasa as a massive, winged man-eater was fully cemented only in 1836, when author John Russell published a fictionalized origin story about a chief who slew the monster. Therefore, the popular concept of the Piasa Bird is a dramatic 19th-century elaboration that contradicts the physical evidence of the historical artwork observed by Europeans in the 17th century.

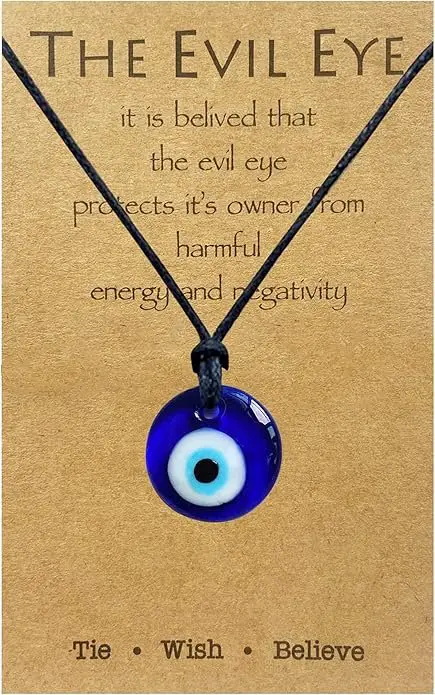

Why Do So Many Successful People Secretly Wear a Little Blue Eye?

Limited time offer: 28% OFF. For thousands of years, the Turkish Evil Eye has quietly guarded wearers from the unseen effects of jealousy and malice. This authentic blue glass amulet on a soft leather cord is the real thing – beautiful, powerful, and ready for you.

What Does the Piasa Bird Look Like?

The physical appearance of the Piasa Bird is subject to significant historical contradiction. The original description, provided by Father Marquette in 1673, details two monsters painted high on the cliff face.

These figures were said to be approximately the size of a calf. The creatures were also a terrifying composite of animal parts. They had horns like a deer’s, a horrific appearance with red eyes, and a beard like a tiger’s beneath a face that somewhat resembled a man’s.

The body was reported to be covered in scales of green, red, and black. Most critically, the primary 1673 documentation describes a wingless creature, focused instead on the long, winding tail. This tail was long enough to pass all around the body, winding above the head and back between the legs, ending distinctly in a fish’s tail.

This collection of features—deer antlers, human face, tiger beard, and fish tail—suggests the original Indigenous artists intended to portray a creature that was a master of the universe as they understood it.

The combination of deer elements (often associated with the Upper World or sky), the scaled, spotted body (This World), and the fish tail (the watery Underworld) meant the Piasa embodied power across all three cosmic domains.

Despite this meticulous historical record, subsequent interpretations, beginning with the 1825 sketch labeled the “Flying Dragon” and popularized by John Russell, overwhelmingly depicted the creature with massive wings, as seen in the 50-foot-wide modern mural re-creations near Alton.

You May Also Like: Bigfoot Sightings Across America: Full 50-State Guide

Habitat

The Piasa Bird is inextricably linked to a singular, dramatic geographic location: the towering limestone bluffs along the Mississippi River, situated near present-day Alton, Illinois. This region, part of the scenic Great River Road, is characterized by sheer cliffs that rise steeply from the water.

The critical importance of this habitat lies in its role as a geographical feature. The painting was originally located near the confluence of the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers. This confluence was historically known for being extremely challenging to navigate, with dangerous rapids and swift currents.

For the Indigenous Illiniwek people, this was not merely a physical hazard but a place imbued with spiritual peril. The Piasa, in its original form as a scaled, snake-like entity, served as a powerful symbol or deity connected to the dangerous, confusing spiritual world—the Underworld, which governs the waters.

The Native American paddlers known to Father Marquette reportedly feared the image. They may have left offerings to placate the entity and ensure safe passage through the treacherous waters.

Unfortunately, the original habitat and the painting itself were destroyed in the 1850s by industrial quarrying, which permanently removed a large section of the bluff face.

Therefore, the Piasa Bird now occupies a conceptual habitat defined by memory and folklore. The current representation—a large, multicolored mural—is painted on a nearby cliff in Piasa Park, ensuring the location remains a cultural focal point.

Ever Walk Into a Room and Instantly Feel Something Watching You?

Millions have used burning sage to force out unwanted energies and ghosts. This concentrated White Sage & Palo Santo spray does the same job in seconds – just a few spritzes instantly lifts stagnation, breaks attachments, and restores peace most people feel immediately.

Piasa Bird Sightings

Documented sightings of the Piasa Bird primarily refer to the observation and recording of the large pictograph, rather than encounters with a living animal. The history of the image spans from the Mississippian period through the era of European exploration and subsequent American mythologizing.

| Date | Place | Witness Details | Description | Reliability |

| Pre-1673 | Alton, Illinois Bluffs | Illiniwek and local Native American tribes | Original painting dating to the Mississippian period (AD 1000–1500) used for spiritual purposes, possibly dating back 800 years. | High: Anthropological evidence of continuous cultural use. |

| 1673 | Mississippi River near Alton, IL | Father Jacques Marquette & Louis Jolliet | Detailed account of two calf-sized, scaled, horned, wingless monsters painted in green, red, and black. | High: First detailed European documentation/Primary source. |

| c. 1682 | Mississippi River region | Jean-Baptiste-Louis Franquelin (Cartographer) | Sketch of a wingless, dragon-like creature on a map based on explorer descriptions. | High: Corroboration of the serpentine/wingless form. |

| 1699 | Mississippi River near Alton, IL | Father de St. Cosme (French explorer) | Reported the images were badly worn, attributing the damage to Indigenous people firing weapons at the pictographs. | Medium: Corroborates continued existence but notes rapid deterioration. |

| 1825 | Alton, Illinois Bluffs | William Dennis (Artist) | Earliest known artist’s sketch, labeling the creature the “Flying Dragon,” demonstrating early European mythological assimilation. | Medium: Historical sketch documenting the image’s later appearance. |

| 1836 (Publication) | Bluffdale, Illinois | John Russell (Author) | Publication of the highly popular, but fabricated, story about Chief Ouatoga and the man-eating winged “Piasa Bird“. | Low: Fiction presented as fact; High cultural impact. |

| c. 1850s | Alton, Illinois | Quarry Workers | The original painting and rock face were destroyed by industrial quarrying, permanently eliminating the artifact. | N/A: Documentation of artifact destruction. |

Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet, 1673

The foundational record of the Piasa originates from the journal of Father Jacques Marquette, who, alongside Louis Jolliet, led the first European exploration of the middle Mississippi River region.

Marquette described seeing two painted monsters high upon a rock face whose height and length inspired awe. Crucially, Marquette noted the skill of the artwork, finding it difficult to believe that “any savage is their author,” arguing that even good painters in France would struggle to reach the location conveniently to paint them.

This viewpoint, while perhaps intended to praise the work, ultimately dismissed the potential for highly developed Indigenous artistry and contributed to the sense of mystery surrounding the pictographs in European minds.

You May Also Like: The Nimerigar: Cannibalistic Little People of the Rocky Mountains

William Dennis Sketch, 1825

After reports of the images faded near the end of the 17th century—likely due to weathering and to Native Americans discharging their weapons at the paintings as they passed—documentation resurfaced in the early 19th century.

The earliest known sketch of the image was produced in 1825 by artist William Dennis, who labeled the creature the “Flying Dragon”. This sketch marked a turning point. However, the original image was likely severely deteriorated.

Dennis’s interpretation began to assimilate the figure into familiar European mythological archetypes, such as dragons and wyverns, setting the precedent for the later addition of wings.

John Russell’s Legend, 1836

The definitive transformation of the Piasa into the monster known today occurred with the publication of John Russell’s article, “The Bird That Devours Men,” in 1836.

Russell, a teacher living near Alton, published a vivid, dramatic, and largely fabricated legend about the painting. Russell claimed the Piasa Bird was a colossal flying monster that terrorized the Illiniwek for years, devouring men, before being defeated by the heroic Chief Ouatoga using poison arrows.

This narrative, which explicitly introduced the essential elements of vast size, aerial predation, and wings, captured the public imagination. The dramatic simplicity of the hero-slays-monster myth successfully supplanted the complex spiritual meaning of the original Indigenous artwork.

Evidence & Investigations

The Piasa Bird is a fascinating subject in the study of mysterious creatures, mainly because what we know about it comes from historical stories and artworks rather than biological evidence.

The most compelling proof of the Piasa’s past existence comes from the 17th-century rock painting. There are two important French drawings from that era, along with a detailed description written by explorer Jacques Marquette in 1673. These documents help show what the original painting looked like and where it was located before it was destroyed.

Researchers have examined what this painting might have represented, drawing on archaeology and art history to understand its significance within Mississippian culture, which thrived between 1000 and 1500 AD.

Some researchers, such as Dr. Mark J. Wagner, believe the image represents a powerful spirit that combines elements from the world around us. For instance, the creature has a fish tail, linking it to the watery Underworld and suggesting danger and confusion.

Meanwhile, its panther-like body and human face link it to our world, while its antlers hint at a connection to the sky or the Upper World. These interpretations help explain why the Indigenous people viewed this location with fear and why they chose to paint such a striking image near perilous river areas.

On the other hand, the idea of the Piasa Bird as a living creature—a giant, winged being often depicted in 19th-century stories—lacks any solid biological evidence to support it. There haven’t been any confirmed tracks, nests, feathers, or reliable sightings of a creature flying over the Mississippi River.

Most modern references to the Piasa Bird concern a mural created in 1964, which has been restored multiple times and serves to preserve the culture rather than to prove the existence of a cryptid.

Sadly, the original rock painting was destroyed in the 1850s due to quarrying, so researchers can never study it to compare it with later drawings and stories.

You May Also Like: What Is a Pukwudgie? Spirit, Cryptid, or Something Worse?

Theories

Given that the Piasa Bird exists primarily as a subject of changing art and folklore, prevailing theories seek to explain the original meaning of the pictograph and the reasons for its radical transformation into a flying monster.

The Underwater Panther

The most widely accepted explanation, based on historical research, is that the Piasa pictograph represents a mythological creature known as the Underwater Panther, or Mishipeshu, in many Native American cultures.

This creature is a significant figure in the stories of the Great Lakes and the Ohio and Mississippi river areas, often imagined as a powerful being with features of both a cat and a serpent.

A description by explorer Jacques Marquette fits this idea well, as he noted features like a scaled body, a cat-like beard, deer antlers, and a long tail that ends in a fish shape.

This suggests a strong connection to the Underwater Panther (a spirit associated with water and the Underworld), symbolizing unpredictable and dangerous natural forces.

Placing this image high on the cliffs near the tricky confluence of the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers could have served both as a warning to travelers and as a way for people to show respect, possibly by leaving offerings to seek safe passage. This idea helps explain the various unusual features noted in the 17th-century descriptions of the pictograph.

Misidentification and Mythological Convergence

Although the original painting of the Piasa did not show it with wings, the public’s fascination with this creature as a giant, winged predator makes sense when we look at different myths.

Many Indigenous cultures across North America share stories about the Thunderbird, a powerful bird spirit that commands respect. It’s likely that the local story of the Piasa, which originally had a serpent-like shape, blended with these widespread beliefs about great sky gods or bird monsters, especially as European explorers started describing it as a flying dragon.

Interestingly, there’s also a connection to ancient history. A long time ago, North America was home to enormous birds of prey called Teratorns, which existed until about 10,000 years ago.

One type of Teratorn (known as Teratornis merriami) had wings that could stretch up to 12 feet! The existence of these giant birds might have inspired tales about large, terrifying flying creatures.

You May Also Like: Is the Lake Iliamna Monster Alaska’s Real-Life Sea Cryptid?

Fabrication and Sensationalism

The theory of fabrication holds that the Piasa Bird, a well-known figure in folklore, is a 19th-century creation rather than an ancient legend.

In 1836, John Russell shared a story that popularized the name “The Bird That Devours Men.” This story was more about capturing attention and creating excitement than preserving a historical truth. It built a thrilling local myth around a monstrous bird, shifting away from the deeper spiritual meanings of the original pictograph.

At that time, there was a growing interest in romanticized stories about Native American culture and a rise in mass-market publishing. The straightforward tale of a great flying beast being defeated by a brave chief was much more appealing and sellable to readers than the complex realities of the original legend, which involved a deity from the Underworld.

As a result, the Piasa Bird’s story became a fascinating example of how ancient symbols can be changed and simplified to fit modern storytelling.

Comparison with Other Similar Cryptids

The Piasa Bird, as a chimeric blend of snake-like, feline, and avian characteristics, shares conceptual ground with several other creatures in global folklore and cryptozoology, particularly those that exhibit hybrid forms or immense size and flight capabilities.

| Cryptid | Primary Location | Key Trait(s) | Origin Type |

| Thunderbird | North America (Great Lakes, Pacific NW) | Massive, supernatural bird; causes thunder by wing flapping. | Indigenous Mythology |

| Jersey Devil | Pine Barrens, New Jersey | Bipedal, goat/horse head, leathery bat wings, horns, cloven hooves; known for high-pitched scream. | Folk Legend/Demonology |

| Snallygaster | Middletown, Maryland | Half-reptile, half-bird; metallic beak, razor teeth, occasionally depicted with tentacles. | Folk Legend/Newspaper Hoax |

| Mothman | Point Pleasant, West Virginia | Man-like figure with large wings spanning up to ten feet, associated with glowing red eyes. | Modern Cryptid/Folk Horror |

| Ropen | Papua New Guinea | Large, nocturnal, bioluminescent pterosaur-like creature. | Modern Cryptid/Pterosaur Survival |

| Mishipeshu | Great Lakes Region | Underwater Panther; scaled, horned, feline/serpentine creature residing in water; demands offerings. | Indigenous Mythology (Directly related) |

| Flying Head | Northeast U.S. (Iroquois) | Giant, cannibalistic, flying human head with bat wings and talons. | Indigenous Mythology |

| Roc | Middle Eastern/Indian Ocean | Gigantic bird of prey capable of lifting large animals; a common element in literary folklore. | Ancient Mythology/Literature |

| Pamola | Mount Katahdin, Maine | Bird spirit: head of a moose, wings of an eagle, body of a man/animal; dictates weather and causes cold. | Indigenous Mythology |

| Gargoyle | European Architecture/Folklore | Grotesque, winged composite creature, typically serving as a protective architectural feature. | Medieval Folklore/Architecture |

| Wyvern | European Folklore | Bipedal dragon, typically possessing two legs, large wings, and a serpentine body. | Medieval Folklore |

You May Also Like: Who or What Is the Owlman of Mawnan Church?

Is the Piasa Bird Real?

The question of whether the Piasa Bird is real requires a clear distinction between the cultural artifact and the alleged biological entity. From an archaeological and ethnohistorical perspective, the pictograph—the evidence of belief and artistry—was demonstrably real.

The fact that Indigenous people created and interacted with this image, which likely represented the powerful, scaled Underwater Panther, confirms that the underlying cultural force and fear were genuine. The painting served a crucial function, marking a dangerous boundary between the spiritual and physical realms in the river system.

However, the Piasa Bird, as it is currently understood by the general public—a massive, living, winged aerial predator that snatched men from the cliffs—lacks any credible biological evidence of existence.

No cryptozoological investigations have yielded biological samples, remains, or scientifically validated photographs of a creature matching the description. Ultimately, the Piasa Bird’s enduring legacy rests not on its biological existence but on its power as a cultural symbol.