The Minotaur (from Ancient Greek Μινώταυρος, Minōtauros, meaning “Bull of Minos”) is a creature in Greek mythology with the head of a bull and the body of a man.

The famous monster lived at the center of the Labyrinth, an elaborate maze-like construction designed by the architect Daedalus and his son Icarus at the command of King Minos of Crete. The Minotaur was eventually killed by the Athenian hero Theseus.

According to the myths, the Minotaur was born from the union of Pasiphaë (queen of Crete) and a bull sent by Poseidon. This unnatural birth resulted from divine punishment after Minos failed to sacrifice the animal as promised.

Confined to the Labyrinth to conceal the royal family’s shame, the Minotaur subsisted on human sacrifices—seven youths and seven maidens sent every seven or nine years from Athens as tribute following Crete’s victory in a war sparked by the death of Minos’s son Androgeos.

Summary

Overview

The Minotaur is a hybrid monster that symbolizes themes of bestial nature, divine retribution, and human ingenuity.

Its existence stemmed from Minos’s hubris in defying Poseidon, leading to Pasiphaë’s cursed desire for the Cretan Bull. The resulting offspring, originally named Asterion, combined human and bovine features and was imprisoned beneath the palace at Knossos.

The Labyrinth served both as a prison and a mechanism of control, ensuring the Minotaur could not escape while allowing periodic feedings through Athenian tributes.

Theseus volunteered for the third tribute to end the cycle, receiving aid from Ariadne in the form of a ball of thread to navigate the maze. He slew the beast and escaped, marking the end of Crete’s dominance over Athens in the myth.

Key Takeaways

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Names | Minotaur, Minotauros, Asterion, Asterius; from Greek Μινώταυρος (“Bull of Minos“); Asterion meaning “starry” or linked to the constellation Taurus |

| Nature | Mythological hybrid monster |

| Species | Humanoid |

| Appearance | Human male body with bovine head, horns, and tail; muscular, often depicted with fur on head and neck |

| Area | Crete, specifically Knossos |

| Creation | Born to Pasiphaë and the Cretan Bull due to Poseidon’s curse |

| Weaknesses | Vulnerable to edged weapons; disoriented outside Labyrinth; defeated by navigation aids and combat skill |

| First Known | *c. 750–700 BCE, alluded in Hesiod’s *Theogony* and early Attic vase paintings* |

| Myth Origin | Greek mythology, rooted in Minoan bull cults and Aegean palace traditions |

| Strengths | Immense physical strength, heightened senses in confined spaces, relentless aggression |

| Lifespan | Indeterminate; sustained by human sacrifices, no natural death recorded |

| Diet | Human flesh, specifically Athenian youths |

| Habitat | Labyrinth beneath the palace of Knossos |

| Associated Creatures | Cretan Bull (father), Daedalus and Icarus (creators of Labyrinth), Ariadne (half-sister) |

Etymology

The term Minotaur derives from Ancient Greek Minōtauros (Μινώταυρος), a compound of Minōs (Μίνως), the legendary king of Crete, and tauros (ταῦρος), meaning “bull.” Therefore, it translates directly to “Bull of Minos.” This name distinguishes the creature as a property or affliction of Minos rather than a generic bull-man.

In earlier sources, the creature is called Asterion (Ἀστερίων), a name also borne by Minos’s adoptive father, the previous king of Crete. Asterion means “starry one” and may refer to stellar symbolism, as the bull’s head aligns with the constellation Taurus. Hellenistic and Roman authors, including Apollodorus and Ovid, consistently use Minotaurus in Latinized form.

Variant spellings appear in fragmentary texts: Minotauros in some Byzantine manuscripts, reflecting phonetic shifts. The dual naming—Asterion for the child, Minotaur for the monster—highlights the transition from infancy to monstrosity.

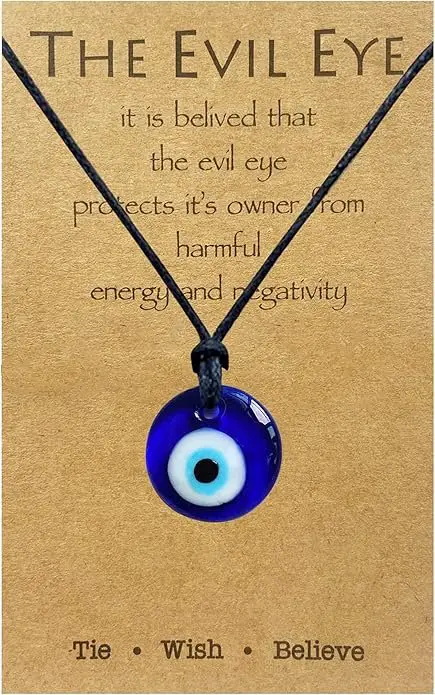

Why Do So Many Successful People Secretly Wear a Little Blue Eye?

Limited time offer: 28% OFF. For thousands of years, the Turkish Evil Eye has quietly guarded wearers from the unseen effects of jealousy and malice. This authentic blue glass amulet on a soft leather cord is the real thing – beautiful, powerful, and ready for you.

Appearance

Ancient depictions of the Minotaur vary slightly but maintain core features.

The creature possesses the torso, arms, and legs of a muscular adult man, typically standing upright. The head is that of a bull—complete with large curved horns, wide nostrils, and a short muzzle. A bovine tail extends from the lower back, often tufted at the end.

Attic black-figure vases (c. 550–500 BCE) show the Minotaur with human skin on the body transitioning to short fur on the neck and head. Red-figure pottery emphasizes anatomical detail, including bulging muscles and veins. Some Hellenistic reliefs add hooves instead of feet, though this is inconsistent; most sources retain human extremities.

The size is generally human-scale but exaggerated in strength. Roman mosaics from the 2nd century CE depict it charging, head lowered, horns forward.

You May Also Like: Fafnir the Lindworm: Poison-Breathing Dragon of Norse Sagas

Origins and Creation

The origins of the Minotaur lie in the complex interplay of divine will, human ambition, and familial shame within the royal house of Crete.

Minos, one of the three sons of Zeus and Europa (along with Rhadamanthus and Sarpedon), sought to secure his claim to the throne of Crete after the death of his stepfather, Asterion.

To demonstrate that the gods favored him above his brothers, Minos prayed to Poseidon, lord of the sea, asking for a sign that would confirm his rightful rule. Poseidon responded by sending a magnificent bull from the waves—a creature of extraordinary beauty, with a coat as white as sea foam and horns that gleamed like polished ivory.

Minos interpreted the bull’s appearance as clear evidence of divine approval. It paraded it before the people of Crete as proof of his mandate. However, when the time came to sacrifice the animal to Poseidon as an offering of gratitude, Minos was overcome by greed and admiration for its perfection.

Instead of offering the divine bull, he substituted an ordinary one from his own herds, believing that the god would not notice or care about the deception. This act of hubris did not go unnoticed. Poseidon, outraged by the broken vow, decided to punish Minos not through direct destruction but by targeting his household in a way that would bring lasting shame.

The god inflicted a curse upon Pasiphaë, the wife of Minos and daughter of the sun god Helios. Under the influence of this divine madness, Pasiphaë developed an uncontrollable and unnatural desire for the white bull.

Consumed by her passion, she confided in Daedalus (the renowned Athenian inventor and craftsman who had been exiled to Crete after committing a crime in Athens). Daedalus, known for his ingenuity in solving impossible problems, agreed to help the queen despite the moral implications of her request.

Daedalus constructed a lifelike, hollow wooden cow, covering it with real cowhide to make it indistinguishable from a living animal. The structure was mounted on wheels so that it could be moved into the meadow where the bull grazed.

Pasiphaë concealed herself inside the wooden contraption, positioning her body to allow the bull to mate with her. The bull, deceived by the device’s realistic appearance and scent, mounted it and fulfilled Pasiphaë’s cursed longing.

In due time, Pasiphaë gave birth to a child that was neither fully human nor fully beast. The infant, initially named Asterion after Minos’s adoptive father, had the body of a human male but the head of a bull, complete with horns, a muzzle, and bovine ears.

As the child grew, his bestial nature became increasingly apparent—he exhibited immense strength, a ferocious appetite, and uncontrollable rage. The people of Crete whispered that he devoured human flesh, and his presence became a source of terror and disgrace for the royal family.

Minos, horrified by the monster that had appeared from his wife’s union, sought guidance from the Oracle at Delphi. The oracle advised him neither to kill the creature—lest he anger the gods further—nor to allow it to roam freely.

Instead, Minos ordered Daedalus to design a prison from which escape would be impossible. Thus, the Minotaur was confined, and his existence hidden from the wider world to preserve the dignity of the Cretan throne.

The Labyrinth

The Labyrinth was the architectural masterpiece created by Daedalus to contain the Minotaur. Described in ancient sources as a vast and intricate complex of corridors, chambers, and dead ends, it was built beneath the palace at Knossos.

The design was so convoluted that even Daedalus himself reportedly had difficulty finding his way out after completion. The structure incorporated countless twisting passages that looped back on themselves, blind alleys that led nowhere, and echoing halls that disoriented anyone who entered.

The name Labyrinth is believed to derive from the Minoan word labrys, referring to the double-headed axe, a prominent symbol in Cretan religion that appeared frequently in palace decorations.

Some scholars suggest that the Labyrinth was not merely a fictional maze but a symbolic representation of the sprawling, multi-level palace at Knossos itself, which contained over 1,300 rooms and a layout that would confound outsiders.

In fact, recent archaeological excavations have revealed staircases leading in multiple directions, storerooms, and ritual spaces that could easily inspire tales of an inescapable prison.

Once completed, the Minotaur was led into the deepest recesses of the Labyrinth, where iron gates were sealed behind him.

The creature adapted to its environment, learning to navigate the darkness using its acute senses of smell and hearing. Food was provided periodically through openings in the structure. Still, the Minotaur’s growing hunger for human flesh would soon demand a more systematic supply.

You May Also Like: Sleipnir: The Terrifying Eight-Legged Horse of Norse Mythology

The Athenian Tribute

The establishment of the Athenian tribute stemmed from a tragic incident involving Minos’s son, Androgeos. It escalated into a mechanism for both vengeance and sustenance for the Minotaur.

Androgeos (a youth of exceptional athletic prowess) traveled to Athens to participate in the Panathenaic Games, a major festival honoring Athena. He dominated every event he entered—wrestling, running, boxing, and the pancratium—earning widespread admiration but also stirring envy among the Athenian nobility and the sons of King Aegeus.

Fearing that Androgeos’s victories diminished their own prestige, certain Athenians plotted against him. In one version of the myth, Aegeus himself, wary of Cretan influence, sent Androgeos on a perilous mission to slay the Marathonian Bull.

This ferocious beast was ravaging the countryside near Marathon. This bull was distinct from the Cretan Bull (the Minotaur’s father). He had been released earlier after Heracles captured it during his seventh labor.

Androgeos confronted the creature but was gored to death, his body mangled beyond recognition.

Alternative accounts suggest that Androgeos was ambushed and murdered by rivals on the road to Marathon, or even that he was killed during the games themselves in a fit of jealousy.

Regardless of the exact circumstances, news of his death reached Minos, who was devastated and infuriated. He viewed the killing as an affront not only to his family but to the divine protection afforded to Crete by Poseidon.

Minos assembled a powerful fleet and launched a war against Athens. The Cretans, masters of the sea, blockaded Athenian ports and laid siege to the city. To compound Athens’s suffering, Minos prayed to Zeus for additional punishment.

Zeus responded by sending a devastating plague that decimated the population and withered crops. With no relief in sight and their forces weakened, the Athenians consulted the Oracle at Delphi for guidance on how to end the calamity.

The oracle declared that the afflictions would cease only if Athens agreed to pay an annual tribute to Crete: seven of their finest young men and seven of their most virtuous maidens, to be sent every seven years (or, in some sources, every nine years) to be devoured by the Minotaur in the Labyrinth. This grim agreement was ratified, and the first tribute was prepared.

The selection process was heartbreaking. Lots were drawn publicly among the noble families of Athens, ensuring that the victims came from the city’s elite to maximize the psychological impact.

The chosen youths were dressed in black robes and paraded through the streets before boarding a ship with black sails—a symbol of mourning and inevitable doom.

Upon arrival in Crete, they were paraded before Minos and the court, then marched to the entrance of the Labyrinth. Guards opened the gates, pushed the victims inside, and sealed the doors.

The first tribute vanished without a trace. The second followed nine years later, with the same ritual and the same outcome. Whispers spread through Athens of the monster’s roars echoing from the ship as it sailed away, and parents lived in dread of the lottery.

The tribute became a cycle of terror that weakened Athens both demographically and spiritually, reinforcing Cretan dominance over the Aegean.

You May Also Like: Huldra: The Beautiful Forest Demon of Scandinavia

Theseus and the Third Tribute

By the time of the third tribute, the people of Athens had endured nearly two decades of this horrific obligation.

Theseus, the son of King Aegeus (and, in some traditions, also claimed by Poseidon as his divine offspring), had grown into a young man renowned for his strength, courage, and sense of justice.

Having already performed feats such as clearing the road from Troezen to Athens of bandits (like Sinis and Procrustes), Theseus volunteered to join the tribute not as a victim but as a liberator.

Aegeus pleaded with his son to reconsider, fearing the loss of his only heir. However, Theseus reassured him, promising that if he succeeded in slaying the Minotaur, he would change the ship’s sails from black to white on the return voyage as a signal of victory.

Reluctantly, Aegeus agreed, and Theseus took the place of one of the selected youths. The ship departed Athens under the customary black sails, carrying fourteen young Athenians toward what was expected to be their doom.

Upon docking in Crete, the tribute group was presented to King Minos in the grand courtyard of the Knossos palace. Minos, ever arrogant, inspected the youths and mocked Theseus specifically, questioning his parentage and bravery.

To assert his authority, Minos removed a golden ring from his finger. It flung it into the harbor, challenging Theseus to retrieve it if he truly had divine blood. Theseus dove into the depths without hesitation.

Guided by dolphins sent by Amphitrite (Poseidon’s wife), he recovered the ring. He appeared triumphant, silencing the court and earning Minos’s grudging respect.

That evening, Ariadne, the eldest daughter of Minos and Pasiphaë, observed Theseus from afar and was immediately smitten by his heroism and demeanor. Unable to bear the thought of his death, she resolved to help him.

Under the cover of night, she sought out Daedalus in his workshop. The inventor, sympathetic to the Athenians and perhaps remorseful for his role in creating the monster and its prison, revealed the secret to surviving the Labyrinth: a ball of thread (known as a clew). The thread should be tied to the entrance and unwound as one progressed inward; to escape, one needed only to follow it back.

Ariadne stole away to Theseus’s quarters and presented him with the thread and a sharp sword forged in the palace armory. In some versions, she also gave him a radiant crown crafted by Hephaestus, which emitted light to illuminate the dark passages.

In exchange for this aid, Theseus swore to take her with him back to Athens and marry her. Ariadne agreed, driven by love and a desire to escape her father’s tyrannical rule.

At dawn, the guards led the fourteen youths to the Labyrinth’s entrance—a massive bronze gate adorned with bull motifs. Theseus entered first, securing one end of the thread to a pillar outside. The others followed in a chain, clutching each other’s hands.

As the gates clanged shut behind them, darkness enveloped the group. Theseus unwound the thread carefully, marking turns with scratches on the walls when possible.

The Labyrinth was a realm of confusion: corridors branched unpredictably, some sloping upward into dead ends, others descending into echoing voids. The air grew thick with the stench of decay and the distant bellows of the Minotaur.

The youths trembled, but Theseus urged them onward, his voice steady. After hours of winding paths—dodging false exits and retracing steps when the thread grew taut—they reached the central chamber.

The Minotaur lay slumbering on a bed of bones, its massive chest rising and falling. Awakened by the intruders’ footsteps, it rose with a thunderous roar, its red eyes glowing in the dim light from Ariadne’s crown. The beast charged, lowering its horns to impale the nearest youth. Theseus shouted for the others to scatter and hide in the alcoves.

The battle was fierce. The Minotaur swung its head like a battering ram, splintering stone walls. Theseus dodged nimbly, using techniques he had learned from Cretan bull-leapers—grabbing the horns to vault over the creature’s back. He slashed at its flanks with the sword, drawing streams of dark blood.

Enraged, the Minotaur cornered him against a wall, but Theseus rolled beneath the charge and drove the blade into its exposed throat. In some accounts, he forsook the sword entirely, wrestling the beast to the ground and pummeling its skull with his fists or a club fashioned from a broken pillar until it lay still.

With the Minotaur dead, Theseus retrieved the thread. It led the surviving Athenians (all fourteen, in most versions) back through the maze. They emerged at dusk to find Ariadne waiting with a small boat. That night, under the cover of darkness, the group sabotaged the Cretan fleet by boring holes in the hulls, then sailed away with Ariadne aboard.

The return journey was bittersweet. Theseus, overcome with grief or distracted by the battle, forgot to hoist the white sails. Aegeus, watching from the cliffs of Sounion, saw the black sails approaching and, believing his son lost, threw himself into the sea, which thereafter bore his name, the Aegean.

Ever Walk Into a Room and Instantly Feel Something Watching You?

Millions have used burning sage to force out unwanted energies and ghosts. This concentrated White Sage & Palo Santo spray does the same job in seconds – just a few spritzes instantly lifts stagnation, breaks attachments, and restores peace most people feel immediately.

Alternative Accounts

While the core narrative of Theseus and the Minotaur dominates classical sources, several variant traditions and tangential stories provide additional layers to the myth.

In Bacchylides’s Dithyramb 17 (5th century BCE), the focus shifts to Theseus’s sea-diving feat before entering the Labyrinth. Minos, aboard the tribute ship, taunts Theseus by throwing his ring overboard and demanding proof of his divine paternity.

Theseus leaps into the ocean, where he is welcomed into Poseidon’s underwater palace. Nereids present him with the ring and a purple cloak, and dolphins escort him back to the surface. This episode establishes Theseus’s heroism and legitimacy before the confrontation with the Minotaur.

Heracles’s seventh labor intersects with the Minotaur’s lineage through the Cretan Bull. Tasked by Eurystheus to capture the beast alive, Heracles traveled to Crete, wrestled the bull into submission, and transported it back to the Peloponnese.

After the presentation to Eurystheus, the bull was released and wandered to Marathon, where it terrorized the region until Theseus later subdued it. This connection positions the Minotaur’s father as a shared antagonist in heroic cycles.

In Book VI of the Aeneid, Virgil describes a temple in Carthage where Aeneas views bronze doors engraved with scenes from Cretan history.

Among them is the Minotaur depicted as mixtum genus (“mixed kind”) and infamis labor (“monstrous offspring of Pasiphaë”). Theseus is shown extending a thread to guide the youths out, with Ariadne portrayed in a moment of compassionate intervention. The scene emphasizes pity and the tragedy of unnatural love rather than heroic combat.

Plutarch, in his Life of Theseus, rationalizes elements of the myth. He suggests that “Minotaur” was a nickname for a brutal Cretan general named Taurus who demanded human tribute, and that the Labyrinth represented the oppressive Minoan palace system.

The “thread” becomes a metaphor for diplomatic cunning or a literal guide through prison corridors. While euhemeristic, this interpretation preserves the structure of sacrifice and liberation.

Diodorus Siculus (1st century BCE) expands on the tribute’s duration, claiming it occurred annually rather than every seven or nine years, and that Theseus’s victory ended a broader practice of human sacrifice across Crete. He also notes that some Cretans denied the monster’s existence, attributing the devoured youths to gladiatorial games in honor of Androgeos.

Finally, Hellenistic art and fragmentary vase paintings occasionally depict the Minotaur with more anthropomorphic traits—such as speaking or wearing armor—suggesting localized variants where the creature was a cursed prince rather than a mindless beast. These alternatives, though minor, illustrate the myth’s adaptability across regions and eras.

You May Also Like: The Mare: The Nightmare Monster That Crushes Men in Their Sleep

Powers and Abilities

The formidable Minotaur is distinguished not by supernatural gifts but by its incredible physical attributes and mastery of its environment.

- Superhuman Strength: This beast can effortlessly subdue multiple armed opponents simultaneously, demonstrating a raw physical power that allows it to lift and throw heavy objects with ease. With muscles honed through years of navigating its labyrinthine home, the Minotaur excels in hand-to-hand combat, using its sheer force to dominate foes.

- Bull Charge: When the Minotaur unleashes its signature bull charge, it becomes a living projectile. With a combination of great speed and mass, it can impale adversaries on its formidable horns or trample them underfoot, turning a simple charge into a deadly assault.

- Heightened Senses: The Minotaur has developed acute senses that enable it to navigate the labyrinth in complete darkness. It relies on its exceptional sense of smell to detect intruders and prey. At the same time, its acute hearing allows it to pick up even the faintest sounds, making it a relentless hunter in the maze’s shadows.

- Durability: This creature’s thick skull and rugged hide offer considerable protection against physical blows, making it resilient against blunt-force attacks. Only deep, penetrating cuts can threaten its life, reflecting its unique adaptations to its treacherous environment.

- Labyrinth Mastery: The Minotaur possesses an intimate knowledge of the intricate maze it inhabits. This familiarity allows it to execute ambush tactics with remarkable efficiency, using the labyrinth’s twists and turns to outmaneuver and surprise those who dare to enter its domain. Whether waiting in the shadows or leading intruders astray, the Minotaur turns its environment into an extension of its lethal capabilities.

Minotaur vs Other Monsters

| Monster Name | Origin | Key Traits | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centaur | Greek | Half-man, half-horse; wild, skilled archers | Wine, organized attacks |

| Cyclops | Greek | One-eyed giant; strong builders, shepherds | Blinding the eye, outsmarting |

| Satyr | Greek | Goat-legged men; playful, music lovers | Restraint from revelry |

| Chimera | Greek | Lion-goat-snake body; fire-breathing | Hero with spear, like Bellerophon |

| Cerberus | Greek | Three-headed dog; guards underworld | Lulled by music, sedative |

| Sphinx | Greek/Egyptian | Lion body, woman head; riddles | Solving riddles |

| Medusa | Greek | Snake-haired woman; turns to stone gaze | Reflection in shield, sword |

| Hydra | Greek | Multi-headed serpent; regrows heads | Fire on necks, single blow to last head |

| Harpie | Greek | Bird-women; snatch food, carry off people | Traps, arrows |

| Siren | Greek | Bird-women singers; lure to death | Wax in ears, tied to mast |

| Werewolf | Greek/European | Man turns to wolf; bites spread curse | Silver weapons, wolfsbane |

| Manticore | Persian/Greek | Lion body, human head, scorpion tail; shoots spines | Strong heroes, arrows |

You May Also Like: Was the Kraken Real? The Origins of a Norse Horror Legend

Conclusion

The Minotaur myth combines many elements of Minoan and Greek culture. The formidable creature, the Minotaur—half-man, half-bull—represents the raw, untamed power that challenges civilization.

Its defeat at the hands of the heroic Theseus not only signifies the triumph of intellect and bravery over physical dominance but also reflects the broader societal ideals of freedom and enlightenment over oppression and tyranny.

This narrative is deeply rooted in the labyrinthine palace of Knossos, a symbol of both grandeur and confinement. In this place, the complexities of human experience unfold.

The Labyrinth, traditionally seen as an intricate maze designed by Daedalus, mirrors the convoluted journey Theseus faces as he navigates both the physical and symbolic obstacles on his quest.

The eventual destruction of the Minotaur represents not only the monster’s demise but the collapse of tyrannical forces, heralding a new era of rationality and democratic ideals.

Significantly, the Minotaur remains a unique figure within the mythological landscape—without progeny or recurrence—symbolizing a definitive end to its reign of terror.