The Lernaean Hydra (often simply called the Hydra) is a snake-like monster from Greek mythology. According to myths, the monster inhabited the swamps of Lerna in the Argolid region. It also served as a guardian of the entrance to the Underworld.

The Hydra was the offspring of Typhon and Echidna (making it a sibling to other monsters such as Cerberus and the Chimera). Raised by Hera to oppose Heracles, the beast terrorized local populations by emerging from its lair to attack livestock and villagers.

The creature was terrifying. It allegedly had multiple heads (ranging from five to one hundred), poisonous breath, and blood that could kill on contact.

As the second labor of Heracles, its defeat required the hero to sever its heads while preventing regeneration through cauterization.

Summary

Key Takeaways

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Names | Lernaean Hydra, Hydra of Lerna; from Ancient Greek Λερναῖα ὕδρα (Lernaîa Húdrā), combining Lernaîa (of Lerna) and húdrā (water snake). |

| Nature | Chthonic monster, serpentine lake guardian. |

| Species | Beast. |

| Appearance | Gigantic serpent with multiple heads (typically nine), poisonous fangs, no legs, aquatic features. |

| Area | Swamps of Lerna near Argos, Greece. |

| Creation | Born from Typhon and Echidna, raised by Hera. |

| Weaknesses | Cauterization of neck stumps prevents head regrowth; immortal head requires burial under rock. |

| First Known | c. 700 BC, Hesiod’s Theogony. |

| Myth Origin | Greek mythology, tied to Heracles’ labors and Hera’s enmity. |

| Strengths | Regeneration of heads (two grow per one severed); poisonous breath and blood. |

| Lifespan | Immortal unless fully decapitated and cauterized. |

| Diet | Livestock, humans, villagers. |

| Associated Creatures | Cerberus, Chimera, Ladon (siblings); Carcinus (crab ally). |

Who or What Is the Hydra?

The Hydra is a multi-headed serpentine monster in Greek mythology, known for its residence in the Lerna swamps and its role as a formidable adversary in Heracles’ Twelve Labors.

As the offspring of the primordial monsters Typhon and Echidna, it embodies chaotic forces of nature, particularly the dangers of marshlands and water sources. The creature’s heads, varying in number across accounts, each possess independent movement and venomous capabilities, making it a persistent threat to nearby settlements.

In the broader context of Greek lore, the Hydra functions as a chthonic guardian, blocking access to the Underworld through its lair at the spring of Amymone. Its attacks on Argive flocks and people prompted King Eurystheus to assign its slaying to Heracles, highlighting the hero’s role in civilizing wild regions.

Unlike humanoid monsters, the Hydra lacks speech or cunning, relying on brute force and biological defenses. Its defeat marked a turning point in Heracles’ penance, providing him with poisoned arrows for future labors.

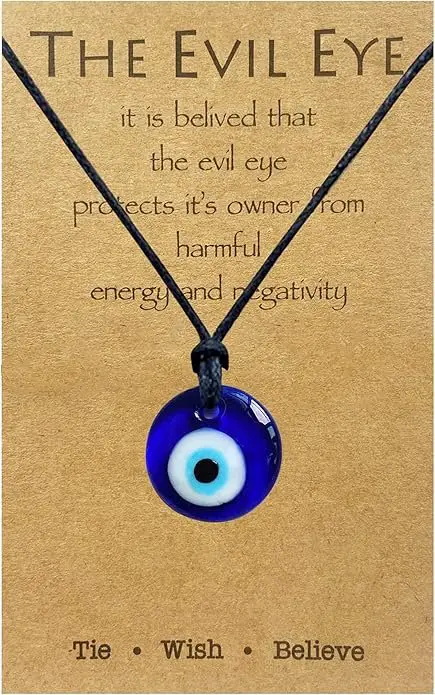

Why Do So Many Successful People Secretly Wear a Little Blue Eye?

Limited time offer: 28% OFF. For thousands of years, the Turkish Evil Eye has quietly guarded wearers from the unseen effects of jealousy and malice. This authentic blue glass amulet on a soft leather cord is the real thing – beautiful, powerful, and ready for you.

Etymology

The name Hydra derives from the Ancient Greek word húdrā (ὕδρα), meaning “water snake” or “aquatic serpent.” This term originates from húdōr (ὕδωρ), the Greek word for “water,” reflecting the creature’s association with marshy environments.

The full designation, Lernaîa Húdrā (Λερναῖα ὕδρα), incorporates Lernaîa, an adjective denoting origin from Lerna. Etymologically, húdrā connects to Indo-European roots for water creatures, such as Sanskrit udrá- (water serpent) and Avestan udra- (otter-like being), suggesting a shared Proto-Indo-European motif of serpentine water guardians.

Variations in nomenclature appear in ancient texts. Hesiod’s Theogony (c. 700 BC) simply calls it the “Lernaean Hydra,” emphasizing its locale without specifying head count.

Later poets like Alcaeus (c. 600 BC) fixed the heads at nine, influencing subsequent Roman adaptations such as Ovid’s Metamorphoses, where it remains Hydra Lerna. The prefix Lernaean ties directly to Lerna, a site with Mycenaean-era cult significance, possibly predating the myth. In Latin, it becomes Hydrus Lerna or simply Hydra, preserving the aquatic essence.

Some scholars trace húdrā to earlier Near Eastern influences, in which multi-headed serpents, such as the Sumerian seven-headed dragon slain by Ninurta, parallel the Greek form.

Rationalizing authors, such as Palaephatus (c. 300 BC), reinterpreted Hydra as a single snake with offspring, deriving the multi-head illusion from its brood.

By the Roman era, Virgil’s Aeneid used the Hydra proverbially to refer to insurmountable tasks, and the term evolved into “hydra-headed” for persistent problems.

You May Also Like: Minotaur: Half Man, Half Bull—The Monster Born of Divine Punishment

What Does the Hydra Look Like?

Ancient depictions of the Hydra portray it as a massive, legless serpent with an elongated body adapted for swamp navigation. Its skin is scaled and iridescent, blending with murky waters. At the same time, the heads—typically nine, though sources vary from five to fifty—rise independently from a shared neck cluster.

Each head features a wide maw lined with curved fangs dripping venom, and eyes that glow faintly in low light. The central head, immortal in many accounts, is larger and crowned with a crest-like fin.

The creature’s body measures up to fifty feet, coiling through mud and reeds, with clawed fins aiding propulsion in water. No limbs encumber its form, emphasizing serpentine grace.

Vase paintings from the 6th century BC show heads of varying sizes, some hooded like cobras, others with manes of smaller snakes. Roman mosaics add bulkier torsos, but core traits remain: toxic breath that manifests as a greenish mist, and blood that darkens the earth on contact.

In Boeotian fibulae (c. 700 BC), it appears with six heads, establishing the multi-headed motif early.

Mythology

The Hydra has a central role in Greek mythology as a primordial chthonic monster, first cataloged systematically in Hesiod’s Theogony (c. 700 BC, lines 270–336, 820–868). Here, it appears as the eldest offspring of Typhon—a hundred-headed storm giant—and Echidna, the “she-viper” residing in Arima’s cave.

Hesiod lists the Hydra alongside siblings Cerberus, Orthrus, the Chimera, and the Sphinx, forming a dynasty of chaos-spawn destined to challenge Olympian order. Unlike its fire-breathing kin, the Hydra’s domain is aqueous decay, embodying stagnant waters and subterranean filth.

Archaeological evidence predates Hesiod: Caeretan hydria vases (c. 530 BC) depict the slaying scene, while Proto-Attic amphorae (c. 650 BC) from Eleusis show Heracles wrestling a multi-headed serpent, confirming the myth’s oral currency by the 8th century BC.

The Lerna site itself yields Mycenaean pottery (LH III, c. 1400–1200 BC) with serpent motifs, suggesting pre-Homeric cult worship at the Heroön shrine, where Hydra blood may have ritually poisoned the Alcyonian Lake.

However, Hera’s patronage elevates the Hydra beyond mere beast. In Apollodorus’ Bibliotheca (2nd century BC, 2.5.2), she deliberately raises the infant monster in Lerna to plague Argos, channeling divine malice against Heracles, Zeus’s bastard son.

This vendetta motif recurs: Diodorus Siculus (1st century BC) notes Hera’s constellation honors for the Hydra and Carcinus, framing defeat as celestial apotheosis.

Interestingly, the Hydra bears some similarities to many Near Eastern serpents: Sumerian Cur (seven-headed, slain by Ninurta, c. 2100 BC Epic of Anzu); Ugaritic Lotan (seven heads, Baal’s foe, c. 1400 BC Baal Cycle); Hittite Illuyanka (multi-headed earth-dragon).

These inform Greek iterations, with headcounts (7, 9, 50) echoing Semitic numerology. Babylonian Mušmaḫḫu—horned, venomous serpent—directly inspires the Hydra’s toxic profile via Hurrian intermediaries.

Pausanias (2nd century AD, 2.37.4) describes Lerna’s toxic springs, attributing the Anigrus River’s stench to undiluted Hydra blood seeping eternally. Strabo (Geography 8.6.7) links it to Hera’s Argive temple, where annual purifications reenact the labor. Euripides’ Heracles (c. 421 BC) invokes the Hydra as Heracles’ haunting nemesis, its poison driving his madness.

You May Also Like: Was the Kraken Real? The Origins of a Norse Horror Legend

Legends

Heracles’ Second Labor: The Slaying of the Lernaean Hydra

Heracles reached Lerna’s pestilent swamps for his second labor, dispatched by Eurystheus to eliminate the Hydra terrorizing Argos. The beast nested in a cavern at Amymone’s spring, an Underworld gateway, surfacing to slaughter herds and villagers.

Heracles brought his nephew, Iolaus, and gave him a lion-skin cloak and a cloth mask against miasmic fumes.

The hero started the fight by sending flaming arrows into the monster’s den, forcing the creature to come out and face him. The Hydra surged out—nine heads rearing, fangs gleaming—entwining his legs in crushing coils.

Heracles battered the monster’s heads with his olive-wood club, but each crushed stump birthed two additional heads. Pinned down and surrounded by the monster’s many heads, he called to Iolaus with a torch.

Heracles drew his kopis sword, cutting one of the heads. Immediately, Iolaus seared the neck, cauterizing flesh to stem regrowth. Methodically, they dispatched eight mortal heads, swamp steaming from burnt gore.

Seeing her monster almost defeated, Hera intervened. She sent Carcinus, a monstrous crab, to bite Heracles’ foot. However, the hero managed to crush the crab with one mace hit.

The Hydra’s ninth head—immortal, golden-scaled—started to spit fire. And no matter how much they tried, Heracles and Iolaus couldn’t sever this immortal head.

Then, the goddess Athena appeared with a divine blade. With that weapon, Heracles was able to cut the last head, then entombed the still-spitting fire head under a Mt. Etna boulder on the Elaeus road.

He then skinned the monster’s corpse, soaking his arrows in black blood (an incurable poison).

Ever Walk Into a Room and Instantly Feel Something Watching You?

Millions have used burning sage to force out unwanted energies and ghosts. This concentrated White Sage & Palo Santo spray does the same job in seconds – just a few spritzes instantly lifts stagnation, breaks attachments, and restores peace most people feel immediately.

The Hydra’s Conception and Hera’s Nursing

Long ago, before the Hydra became known for its terrifying nature, it originated in a faraway place called Arima. In a dark cave, the fierce monster Typhon (who had many heads) teamed up with Echidna, and together they gave birth to many fearsome creatures.

According to the ancient poet Hesiod, the Hydra was the first of these monstrous offspring and was cared for in beautiful caves alongside another creature named Cerberus.

However, seeing an opportunity, the goddess Hera kidnapped the young Hydra from Echidna’s other offspring. She then took the Hydra to the springs in Lerna, where she fed it special divine milk that caused it to grow to gigantic proportions.

Another writer, Pherecydes of Athens, mentioned that Hera dipped the baby Hydra in the waters of the River Styx, which not only granted it one immortal head but also cursed the rest of its heads to keep growing back whenever they were cut off.

This transformation turned the Hydra into a guardian of the Underworld and caused trouble for the land by poisoning a sacred water source, leading to droughts.

Local legends from Lerna tell of Hera visiting the Hydra at night, whispering angry spells as the creature consumed offerings of cattle. One story from a lost epic called the Heracleia describes a herdsman named Lernus who witnessed Hera bestow a lunar crown on the beast, causing its heads to multiply to nine.

You May Also Like: The Mare: The Nightmare Monster That Crushes Men in Their Sleep

The Poisoning of the Anigrus and Eternal Curse

After Heracles defeated the Hydra, remnants of the creature cursed the land of Elis.

According to the ancient writer Pausanias, while chasing some cattle for King Augeas, Heracles crossed the Anigrus River. The water became tainted with Hydra blood that clung to his gear, and as a result, any pigs that bathed in the river grew bristles and died while foaming at the mouth.

To help protect their community from this curse, the locals began performing yearly sacrifices in hopes of appeasing the “undying venom” that lingered.

There’s also a similar story from an ancient writer named Sosibius, who lived in the 3rd century BC. He described how the Hydra’s blood spilled onto an altar dedicated to Hera, which made her furious.

Because of this, she declared that Lerna, the place connected to the Hydra, would forever stink. Pilgrims visiting the area would put on clay masks to mimic Heracles and attempt to cross the toxic pools of water that had been poisoned by the Hydra.

Additionally, Diodorus, another ancient writer, noted that Hera forced the river nymphs to keep the Hydra’s essence hidden underground. This essence later surfaced as a powerful healing venom—an ironic twist, since it came from Heracles’ hard-fought victory over the monster.

Dionysus and the Revived Hydra in India

In the epic tales of Nonnus, after the great monster Typhon was defeated, his remnants gathered during Dionysus’s conquests in the east.

As the god’s army crossed the Hydaspes River, the goddess Hera, who still harbored resentment, ordered spirits from the Underworld to spit out heads of a creature known as the Hydra. These heads appeared as ghostly snakes amidst the heavy rains of India.

According to Nonnus, there were fifty of these heads. They spread out across lotus ponds, poisoning wine supplies and transforming Dionysian celebrations into deadly chaos.

But Dionysus had a plan. He used a special staff, called a thyrsus, that was dipped in poisonous venom from the Hydra, which he had received as a gift from Heracles through Hermes.

Meanwhile, his followers (the Maenads), driven into a frenzy by their drums, fought back against the Hydra’s heads with sickle-knives. Still, the heads kept regenerating, sprouting vines that choked the area.

Just when it seemed hopeless, Rhea-Cybele stepped in and brought in panthers to help. While they tore at the roots of the heads, Dionysus poured his wine, mixed with sleep-inducing herbs, into the creatures, causing them to become paralyzed.

However, one head managed to escape to the Ganges River, where it mingled with local water spirits called Nagas and eventually gave rise to multi-headed guardians that were later honored in Hindu stories.

After witnessing Dionysus’ victory, Hera turned the remaining Hydra heads into decorative onyx cameos, which she gave to satyrs as protective charms against becoming too drunk.

You May Also Like: Huldra: The Beautiful Forest Demon of Scandinavia

Hydra vs Other Monsters

| Monster Name | Origin | Key Traits | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yamata no Orochi | Japanese | Eight-headed dragon, demands maidens as tribute. | Sake intoxication, sword strike to tails. |

| Jörmungandr | Norse | World-encircling serpent, venomous. | Thor’s hammer, poison susceptibility. |

| Apep | Egyptian | Chaos serpent, eclipses sun. | Ra’s spear, protective spells. |

| Ladon | Greek | Hundred-headed dragon, guards golden apples. | Heracles’ arrows, slumber inducement. |

| Chimera | Greek | Lion-goat-serpent hybrid, fire-breathing. | Bellerophon’s spear, winged approach. |

| Cerberus | Greek | Three-headed hound, guards Underworld. | Honeyed sedative, music calming. |

| Scylla | Greek | Six-headed sea monster, devours sailors. | Ranged attacks, avoiding straits. |

| Tiamat | Babylonian | Multi-headed sea dragon, primordial chaos. | Marduk’s winds and arrows. |

| Níðhöggr | Norse | Dragon gnawing world tree roots. | Eagle’s intervention, Ragnarok events. |

| Xiangliu | Chinese | Nine-headed serpent, floods land. | Yu the Great’s sword, drainage works. |

| Lotan | Canaanite | Seven-headed sea serpent, storm ally. | Baal’s thunderbolts, divine combat. |

The Hydra shares regenerative multiplicity and serpentine form with creatures like Yamata no Orochi and Xiangliu, both flood-bringers slain by heroes in water-related myths.

However, unlike the world-scale threats posed by Jörmungandr or Apep, the Hydra operates locally, guarding underworld portals akin to those of Cerberus or Ladon.

Fire and cauterization exploit its weakness, paralleling Chimera’s fire breath, countered by aerial strikes or Tiamat’s division by winds.

Overall, similarities lie in multi-headed motifs symbolizing persistent evil, while differences highlight cultural variances: the Greek focus on heroic labors versus the Norse apocalyptic roles.

Powers and Abilities

The Hydra wields formidable biological and environmental powers rooted in its serpentine physiology. Its primary ability, regeneration, allows severed heads to sprout anew, often doubling in number, rendering direct decapitation counterproductive without intervention.

Poison dominates its arsenal: breath emits lethal vapors that corrode flesh and metal, while blood acts as a contact toxin, contaminating water and soil for generations.

In combat, the Hydra uses coordinated head strikes—each independent yet synergistic—that overwhelm foes through sheer volume. Aquatic adaptation enables ambush from swamps, coiling to constrict or drag victims underwater.

Though lacking intelligence, its instincts make it relentless, persisting until starved or fully dismantled. Ancient sources imply minor fire-breath from the immortal head, adding elemental versatility.

The Hydra‘s powers and abilities include:

- Head Regeneration: For each severed head, two regrow unless the stump is cauterized with fire.

- Venomous Breath: Exhales toxic gas, causing immediate respiratory failure or corrosion.

- Poisonous Blood: Fluid kills on contact, used by Heracles to tip arrows for incurable wounds.

- Multi-Head Coordination: Heads attack independently, multiplying strikes and defenses.

- Aquatic Ambush: Swims stealthily in swamps, emerging to ensnare prey with coils.

- Immortal Central Head: One head resists death, requiring burial to neutralize.

- Constriction: Body coils to crush bones, leveraging immense length and strength.

You May Also Like: 15 True Ghost Stories You Shouldn’t Read Alone After Midnight

Conclusion

The Lernaean Hydra is a cornerstone of Greek mythological bestiary, illustrating the perils of unchecked natural forces and the ingenuity required to subdue them. Its integration into Heracles’ labors highlights themes of perseverance, transforming a local menace into a pan-Hellenic emblem of heroic triumph.

Beyond narrative, the creature’s legacy influences proverbial language, denoting escalating difficulties in endeavors from politics to ecology.

Modern interpretations extend the Hydra’s reach, adapting its form to fantasy realms and scientific nomenclature, where real hydra polyps echo its regenerative prowess.

Ultimately, the Hydra reminds us that victory over multiplicity demands holistic approaches—addressing roots, not symptoms—to avert proliferation.