Echidna is a prominent, monstrous figure in Ancient Greek mythology, primarily recognized as the mother of many of the most famous and fearsome creatures and villains.

She is often depicted as a chthonic figure, belonging to the primordial generation of deities and monsters. Her name and lineage firmly establish her as a being of immense, monstrous significance, linking her to foundational concepts of darkness and chaos within the Greek cosmological framework.

Regarded as a primal, half-woman and half-serpent creature, Echidna’s primary role in myth is genealogical. Alongside her mate, the dreaded monster Typhon, she is responsible for producing a terrifying lineage that challenged the Olympian gods and heroes.

Her existence embodies the savage, untamed aspects of nature and the horrifying hybridity that defines so many Greek monsters, solidifying her place as a fundamental creature of fear and mythic importance.

Summary

Key Takeaways

| Attribute | Details |

| Names | Echidna (Greek for ‘She-Viper’), The Mother of All Monsters |

| Nature | Primordial Deity/Monster, chthonic |

| Species | Hybrid (Half-Woman, Half-Serpent) |

| Appearance | Beautiful, fair-cheeked woman from the waist up; monstrous, scaly snake/serpent from the waist down |

| Area | Arima (A land under the earth), Caves in Cilicia, or a cave in a remote, desolate region of the earth |

| Creation | Born from primordial deities (Phorcys and Ceto, or sometimes Tartarus and Gaea) |

| Weaknesses | Could be slain by a hero or deity; Heracles killed her in some accounts |

| First Known | 8th century BCE, Theogony by Hesiod |

| Myth Origin | Ancient Greek Mythology |

| Associated Creatures | Typhon (mate); offspring including Cerberus, the Hydra, the Chimera, the Sphinx, and the Nemean Lion |

| Habitat | Caves or deep places within the earth, reflecting her chthonic nature |

| Lifespan | Immortal in some accounts, but killed by the hero Heracles/Argus Panoptes in others |

Who or What Is Echidna?

Echidna is a fearsome and iconic entity from Greek mythology, famously designated as the ‘Mother of All Monsters.’ She is a primal being, representing the monstrous and untamed elements of the ancient world. Her nature is chthonic, meaning she belongs to the earth and the Underworld, aligning her with the oldest, most foundational forces in the Greek pantheon.

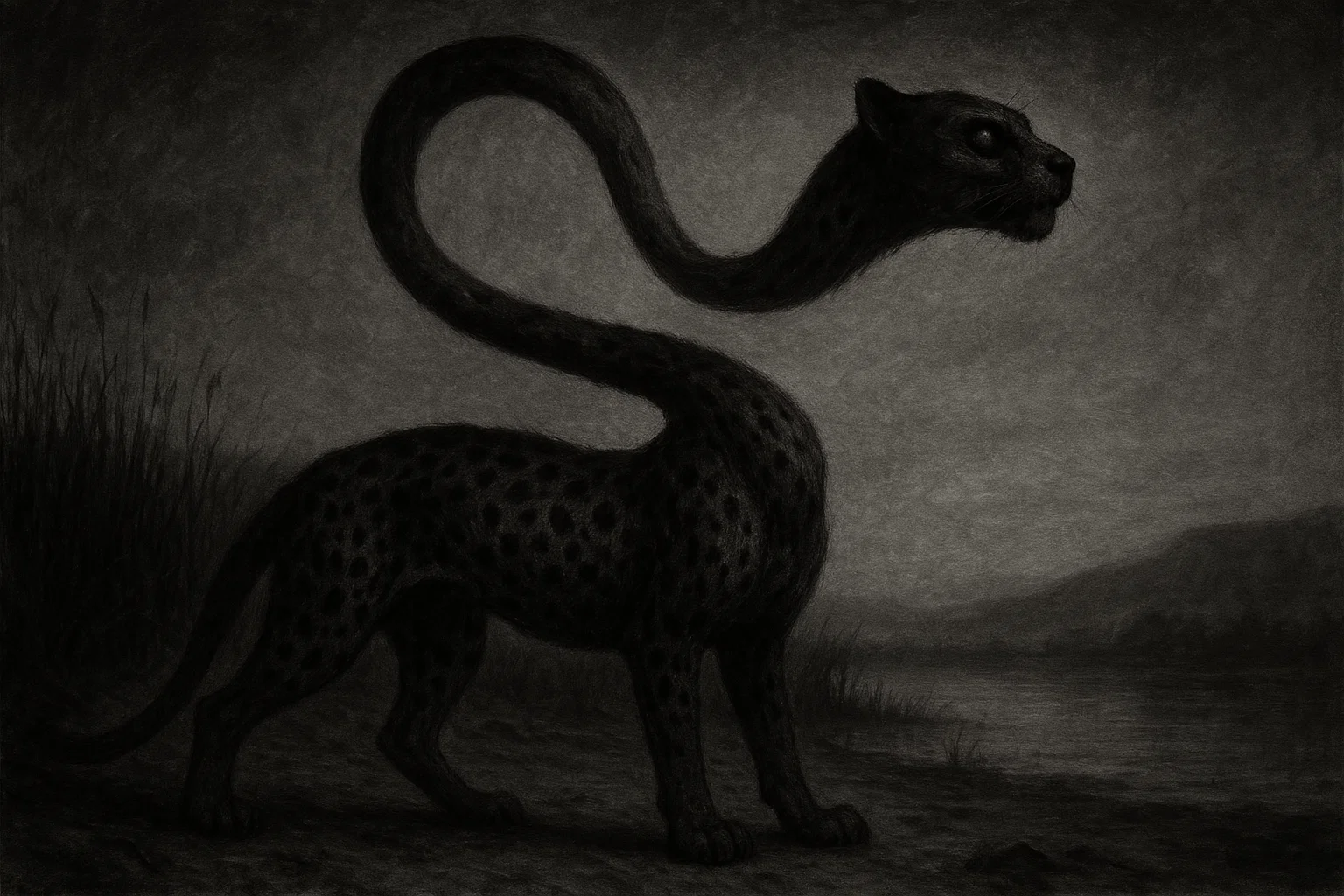

In terms of physical form, Echidna is a hybrid creature.7 She is consistently described as a nymph-like woman from the head to the waist, possessing beauty and fair features. However, from the waist down, her body transforms into that of a monstrous, scaly serpent or snake.

This dual nature of beauty and horror highlights her role as a source of both allure and extreme danger. Her primary significance is her union with the gigantic monster Typhon, as together they are the progenitors of a legion of the most terrifying monsters in classical myth. She is not merely a monster, but a foundational link in the mythological chain of fearsome beasts that heroes like Heracles would later confront.

Why Do So Many Successful People Secretly Wear a Little Blue Eye?

Limited time offer: 28% OFF. For thousands of years, the Turkish Evil Eye has quietly guarded wearers from the unseen effects of jealousy and malice. This authentic blue glass amulet on a soft leather cord is the real thing – beautiful, powerful, and ready for you.

Genealogy

Echidna’s lineage is rooted in the early, primordial deities of Greek myth, though sources vary slightly on her exact parentage.

| Relation | Entity |

| Father | Phorcys (Sea god of the Hidden Dangers) |

| Mother | Ceto (Goddess of the Dangers of the Sea) |

| Mate | Typhon (Monstrous Gigantic Serpentine Creature) |

| Siblings | Gorgons, Graeae, Ladon, Sirens, Hesperides (via Phorcys and Ceto) |

| Offspring | Cerberus (Three-headed dog of Hades) |

| Lernaean Hydra (Multi-headed serpentine water monster) | |

| Chimera (Fire-breathing monster with a lion’s head, goat’s body, and serpent’s tail) | |

| Sphinx (Winged lion with a woman’s head) | |

| Nemean Lion (Lion with impenetrable hide) | |

| Ladon (Dragon guarding the Golden Apples) | |

| Crommyonian Sow (Monstrous wild boar) | |

| Orthrus (Two-headed dog) |

Etymology

The name Echidna derives from the Ancient Greek word ἔχιδνα (ekhidna), which translates directly to ‘she-viper’ or ‘viperess’. This etymology is highly descriptive and reflective of her nature as a monstrous, half-serpentine being. The root of the word, echis (ἔχις), means ‘viper’ or ‘snake,’ firmly linking her identity to the serpent and its associated concepts of earthbound danger, poison, and primal fear.

This naming convention aligns Echidna with the chthonic tradition of Greek mythology, where creatures of the earth, often snake-like or hybrid in form, represent the dark, unformed, and chaotic aspects of the cosmos that predate or oppose the Olympian order.

As a ‘she-viper,’ her name encapsulates her monstrous form and her deadly potential as the mate of Typhon and the mother of numerous deadly progeny. Her name itself is a declaration of her species and her venomous, foundational role in myth.

While the term is primarily a species name for a type of snake, in her specific mythological context, it elevates her to a singular, foundational monster.

The name Echidna has persisted and is even used in modern biology, as it is the genus name for the spiny anteaters (monotremes) of Australia and New Guinea, presumably named for their reptilian, egg-laying, and spiny characteristics, which resonate with the monster’s hybridity. However, the mythological Echidna’s primary significance lies is her terrifying, snake-like lower body, as the name clearly denotes.

You May Also Like: Futakuchi-onna: The Terrifying Two-Mouthed Woman of Japanese Folklore

What Does the Echidna Look Like?

The physical description of Echidna is a classic example of mythological hybridity, contrasting human beauty with animal monstrosity. The most definitive description comes from Hesiod’s Theogony, which is the primary source for her appearance.

From her head to her waist, Echidna is described as a nymph with ‘fair cheeks’ and ‘flashing eyes’. She has the appearance of a beautiful young woman, suggesting a deceptive, alluring quality. However, from the waist down, this human form ceases, giving way to a massive, monstrous serpent. This snake-like lower half is often described as scaly, reflecting the cold, earthbound nature of a viper.

Hesiod states she is ‘a nymph with fair cheeks and flashing eyes, with the body of a serpent, terrible and great, whose scales are speckled, feeding on raw flesh beneath the depths of the earth.’ This duality—the fair-cheeked nymph blending into the terrifying snake—is a core aspect of her monstrous identity, symbolizing the hidden danger and primal chaos she embodies.

Ever Walk Into a Room and Instantly Feel Something Watching You?

Millions have used burning sage to force out unwanted energies and ghosts. This concentrated White Sage & Palo Santo spray does the same job in seconds – just a few spritzes instantly lifts stagnation, breaks attachments, and restores peace most people feel immediately.

Mythology

Echidna’s earliest and most definitive appearance in ancient Greek literature is in Hesiod’s Theogony, a foundational text for Greek cosmology dating to the 8th century BCE.

In this work, she is identified as the monstrous offspring of the sea deities Phorcys and Ceto. However, later accounts suggest Tartarus and Gaea as her parents, solidifying her status as a primordial chthonic force.

In the Theogony, she is immortalized through her union with the fearsome giant Typhon. Typhon was an enormous, catastrophic monster created by Gaea to avenge the Titans by challenging the Olympian gods.

Hesiod describes her as having a secret, permanent living place: ‘There is a hollow cave under a hollow rock far away from the road of gods and mortal men, a dwelling place for her for all time.’ This remote cave setting focuses on her separation from the civilized world, placing her firmly in the realm of the monstrous and untamed.

Her mythic role is not focused on an active narrative of confrontation but rather on her genealogical function. Echidna and Typhon are described as having mated and produced a horrifying brood of monsters that would become central figures in later heroic cycles.

These creatures—including the three-headed dog Cerberus, the poisonous Hydra of Lerna, the fire-breathing Chimera, the riddling Sphinx, and the invulnerable Nemean Lion—represent the untamed savagery that the Olympian order and its heroic champions, most notably Heracles, sought to contain or destroy.

Later sources, such as Apollodorus’s Library, fill in some of the gaps, providing an account of her eventual death. According to this narrative, Echidna was slain by the giant-killer Argus Panoptes, the hundred-eyed giant who, in an earlier myth, was charged with guarding the heifer Io.

Apollodorus states that Argus caught her sleeping and killed her, thus eliminating the ‘mother of monsters.’ However, other traditions credit Heracles with her death, a hero who fought and defeated several of her offspring, perhaps suggesting a symbolic completion of his cycle of labors by eliminating their source.

Regardless of the slayer, her demise marks the containment of a potent, primordial force of chaos.

You May Also Like: Likho: The One-Eyed Crone Who Brings Death and Bad Luck

Legends

Echidna and Typhon: The Progenitors of Monstrosity

The most central and enduring legend concerning Echidna is her union with the gigantic monster Typhon, which led to the birth of a terrifying pantheon of creatures.

As recounted in Hesiod’s Theogony, Echidna and Typhon mated in a remote, shadowy location, leading to a prolific output of monstrous life. The text details that ‘She was joined in love to Typhaon, that lawless one, and bore fierce offspring. ‘

This is not a tale of romance, but of primal, chaotic generation. Typhon himself was the result of Gaea’s rage against the Olympians for imprisoning her Titan sons, a colossal, hundred-headed, fire-breathing entity. Their coupling, therefore, represents the fertile union of two of the most destructive forces in early Greek myth.

The offspring that resulted were not only fearsome but directly related to the greatest challenges faced by Greek heroes and gods. Their children included Cerberus, the fearsome guardian of the Underworld; the Lernaean Hydra, whose severed heads grew back; the Chimera, a tripartite beast that breathed fire; Orthrus, the two-headed dog; and the Nemean Lion, which was impervious to weapons.

This generation of monsters was viewed as embodying the untamed wilderness and the chaotic forces of the earth that the heroes and deities of the new Olympian order were destined to subdue.

The myth’s significance lies is establishing Echidna as the genetic source of Greek heroic challenges, making her existence critical to the structure of later myths.

The Slaying of Echidna

Though her primary role is that of a mother, later traditions recount the end of her existence. One prominent account of her death is found in the writings of the mythographer Apollodorus. According to this legend, Echidna was a creature that often slept, perhaps due to her chthonic nature or her sheer bulk.

The creature credited with her slaying is Argus Panoptes, the giant whose body was covered with one hundred eyes. Argus was already renowned for his strength and alertness, making him an ideal agent for such a task.

The account states that Argus, ‘while Echidna was asleep, came upon her and killed her.’ This act is presented as a crucial step in ridding the world of a great source of evil. By eliminating the progenitor of chaos, the world could become a safer place for men.

Argus’s vigilant, hundred-eyed nature made him the perfect counter to a monstrous creature that might only be vulnerable during moments of repose. The simplicity of the narrative—finding her asleep and killing her—belies the importance of the act, which was the removal of a foundational monster from the world.

A separate tradition, documented in Heracles’ later myths, also suggests that the hero confronted and killed Echidna. In this version, Heracles, while journeying to retrieve the cattle of Geryon (another of Echidna’s kin), came upon her. She allegedly stole some of his cattle, and after recovering them, Heracles was said to have killed her.

This version is somewhat less common but symbolically powerful, as it has Heracles, the slayer of so many of her offspring, ultimately confronting and defeating the mother of all his challenges, thus symbolically concluding his great cycle of labors against the forces of chaos.

You May Also Like: What Is a Centaur? The Greek Monsters Born from Sin

Echidna vs Other Monsters

| Monster Name | Origin | Key Traits | Weaknesses |

| Lamia | Greek Mythology | Half-woman, half-snake/beast, preys on children. | Could have her eyes removed (by Hera) or put back in. |

| Gorgons (e.g., Medusa) | Greek Mythology | Female, serpentine features (hair of snakes), terrifying appearance. | Vulnerable to decapitation (Medusa) and indirect sight/reflection. |

| Melusine | European Folklore | Woman from the waist up, serpent/fish from the waist down (often appearing when bathing). | Betrayal or breach of a private promise by her husband. |

| Dracaenae | Greek Mythology | Female, half-woman, half-serpent, often guards sacred places. | Could be slain by heroes (like the one that guarded the Golden Fleece). |

| Nāgini | Hindu Mythology | Female form of Nāga (serpentine beings), often depicted as beautiful women with serpent tails or hoods. | Certain divine weapons or spells (Mantras). |

| Sirens | Greek Mythology | Half-woman, half-bird (or sometimes fish), lure sailors to their deaths with their singing. | Blocking their song (with wax) or having a superior song (Orpheus). |

| Scylla | Greek Mythology | Half-woman (originally), later a monster with six serpentine necks and dog heads around her waist. | No known effective weakness, considered a natural sea hazard. |

| Vouivre | French Folklore | Winged female serpent with a garnet on her head; sometimes appears as a beautiful woman. | The ruby/garnet on her head is her life-force; stealing it. |

| Yamauba | Japanese Folklore | Mountain hag/witch (sometimes with serpentine features or an extra mouth). | Driven off by loud noises or specific rituals/amulets. |

Echidna shares a deep structural similarity with many hybrid female monsters across cultures, most prominently those with a snake-like or draconic lower body, like the Lamia and the Dracaenae in Greek myth, and the European Melusine.

All these creatures utilize the powerful cultural trope of the beautiful woman merging with the dangerous, chthonic snake, symbolizing hidden danger and the untamed natural world. While the Gorgons also feature snakes, they typically replace hair rather than forming the lower body, distinguishing them slightly.

Furthermore, Echidna’s primary mythological role is genealogical—she is the mother of the greatest monsters—a function not shared by the more narratively focused figures, such as Lamia (a child-eater) or the Sirens (lurers).

Unlike the Nāgini or Vouivre, who often possess a specific life-force or treasure, Echidna’s only noted weaknesses are that she can be slain by a powerful hero or entity like Argus Panoptes or Heracles, marking her as a great, but ultimately mortal, opponent of the Olympian order.

You May Also Like: Mormo: The Terrifying Child-Snatching Monster of Ancient Greece

Powers and Abilities

Echidna, as a primordial monster and the ‘Mother of All Monsters,’ possesses a fundamental level of monstrous power derived from her chthonic nature.

Her primary power lies in her fertility and ability to spawn monstrous life. Her union with Typhon produced a generation of the most devastating and famous creatures in Greek myth, effectively making her the font of the heroic challenges that define the saga of Heracles and others.

Beyond her reproductive role, her hybrid physical form suggests inherent snake-like capabilities. However, they are not extensively detailed in the core texts.

As a creature with the lower body of a viper, she likely possesses immense strength, the ability to move with snake-like speed and stealth, and potentially venomous capabilities. However, this is often implied rather than explicitly stated.

She is described by Hesiod as one who ‘eats raw flesh beneath the depths of the earth,’ indicating a predatory nature and supernatural longevity (or potential immortality), which required a great hero or giant to finally end.

Her powers and abilities include:

- Monstrous Procreation: The ability to mate with Typhon and give birth to numerous powerful and unique monsters, including Cerberus, the Hydra, the Chimera, and the Sphinx.

- Chthonic Nature: A connection to the earth and the primordial forces, granting her a formidable, foundational power.

- Longevity/Immortality: Existing from the era of the Titans until her slaying by Argus Panoptes or Heracles, suggesting a lifespan far exceeding mortals.

- Predatory Sustenance: The ability to sustain herself on ‘raw flesh,’ indicating a powerful, carnivorous nature.

- Snake-like Movement: Possessing a great, scaly serpent body allows for powerful, rapid, or stealthy movement, typical of mythical vipers.

Can You Defeat an Echidna?

According to the later traditions of Greek mythology, Echidna is a monster that can be defeated and killed. While her exact nature as a primordial deity or a mere monster grants her immense power and longevity, she is not presented as an immortal being beyond the reach of powerful heroes or gods.

The most famous account of her demise credits the all-seeing giant Argus Panoptes with her death. Argus found Echidna sleeping and slew her while she was vulnerable.

This suggests that a direct, decisive attack, particularly when she is unaware or weakened, is an effective way to destroy her. Another tradition credits the hero Heracles with her defeat and death, though the circumstances are less detailed.

Given Heracles’ record of defeating her powerful offspring, his success against the mother of all monsters is credible, implying that a hero of divine strength and cunning is required.

In terms of warding her off, given her chthonic and remote habitat, the primary ‘protection’ was geographical distance. She was said to live in a remote cave far from both gods and mortals, making direct confrontation rare.

As she represents the primal chaos, her defeat is ultimately a mythic act performed by an agent of order (Argus) or a great hero (Heracles) to ensure the safety of the civilized world, rather than a task achievable by ordinary mortals.

You May Also Like: What Is a Satyr, the Lust-Driven Monster of the Wild?

Conclusion

Echidna holds a unique and crucial position in the tapestry of Greek mythology, not primarily through her active deeds, but as the genealogical root of monstrous chaos.

Her hybrid form—half-beautiful woman, half-terrifying serpent—captures the seductive, primal danger of the untamed world. As the mate of Typhon and the mother of legends like Cerberus, the Hydra, and the Chimera, she ensured that the forces of savagery would remain a constant, formidable challenge for the gods and heroes of the emerging Olympian order.

The legends surrounding Echidna focus heavily on her procreative power, establishing her as the literal source of the monstrous adversaries that define the great heroic cycles, particularly the labors of Heracles.

Her ultimate slaying by either Argus Panoptes or the hero Heracles symbolizes a victory for cosmic order, demonstrating that even the most foundational forces of chaos can eventually be contained or destroyed.