The Chimera is a hybrid monster from Greek mythology, known for its composite form drawn from multiple animals and its ability to breathe fire. The monster allegedly inhabited the region of Lycia in Asia Minor and caused destruction by ravaging livestock and settlements.

Its legend appears in key texts such as Homer’s Iliad and Hesiod’s Theogony, where it symbolizes unnatural chaos. Records from ancient sources describe the Chimera as the offspring of the monsters Typhon and Echidna, placing it among a family of formidable beasts including Cerberus and the Hydra.

The creature was eventually slain by the hero Bellerophon, who used the winged horse Pegasus to gain an advantage in battle.

Summary

Key Takeaways

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Names | Chimera, Chimaera, Khimaira; from Ancient Greek Χίμαιρα (Chímaira), meaning “she-goat” |

| Nature | Monster, hybrid beast |

| Species | Hybrid (lion-goat-serpent) |

| Appearance | Body and head of a lion, goat’s head rising from back, serpent for tail; fire-breathing |

| Area | Lycia, Asia Minor (modern southwest Turkey) |

| Creation | Offspring of Typhon and Echidna |

| Weaknesses | Vulnerable to aerial attacks; lead-tipped weapons that melt in fire breath; slain by single hero with divine aid |

| First Known | 8th century BCE, Homer’s Iliad (Book 6 and 16) |

| Myth Origin | Greek mythology, with possible influences from Near Eastern art and Hittite sculptures |

| Strengths | Fire-breathing; combined physical traits of lion strength, goat resilience, serpent venom |

| Associated Creatures | Siblings: Cerberus, Lernaean Hydra; offspring in some accounts: Nemean Lion, Sphinx |

| Diet | Livestock, humans; destructive to countryside |

Who or What Is Chimera?

The Chimera is a fire-breathing hybrid monster in Greek mythology, composed of the parts of a lion, a goat, and a serpent. It lived in the mountains of Lycia and terrorized the local population by destroying crops, killing cattle, and attacking people.

Ancient accounts portray it as a creature of divine but monstrous origin, too powerful for ordinary men to defeat.

According to the myth, the beast was born to Typhon (a storm giant) and Echidna (a half-woman, half-serpent creature), making it part of a lineage of destructive entities.

The Chimera’s presence was often linked to omens of disaster, such as earthquakes or fires, reflecting its role as an embodiment of natural upheaval. King Iobates of Lycia tasked the hero Bellerophon with slaying it, providing a narrative of human ingenuity overcoming primal terror.

In a broader mythological context, the Chimera stands apart from other hybrids by its specific tripartite form and fiery nature. It challenged heroes not through riddles or cunning, but through raw ferocity and elemental power.

The creature’s defeat marked Bellerophon’s rise, though his later hubris led to his downfall, underscoring the perils of mortal ambition.

Genealogy

| Relationship | Details |

|---|---|

| Father | Typhon (storm giant with multiple heads, son of Gaia and Tartarus) |

| Mother | Echidna (half-woman, half-serpent; known as the “Mother of Monsters”) |

| Siblings | Cerberus (three-headed hound guarding the Underworld); Lernaean Hydra (multi-headed serpent slain by Heracles); Orthrus (two-headed dog guarding Geryon’s cattle); Caucasian Eagle (bird that tormented Prometheus, in some accounts) |

| Offspring | Sphinx (riddle-posing creature of Thebes; born from the union with Orthrus); Nemean Lion (invulnerable beast slain by Heracles; also from Orthrus) |

| Grandparents (Paternal) | Gaia (Earth); Tartarus (the abyss beneath the Underworld) |

| Grandparents (Maternal) | Phorcys and Ceto (sea deities; parents of Echidna in some traditions) |

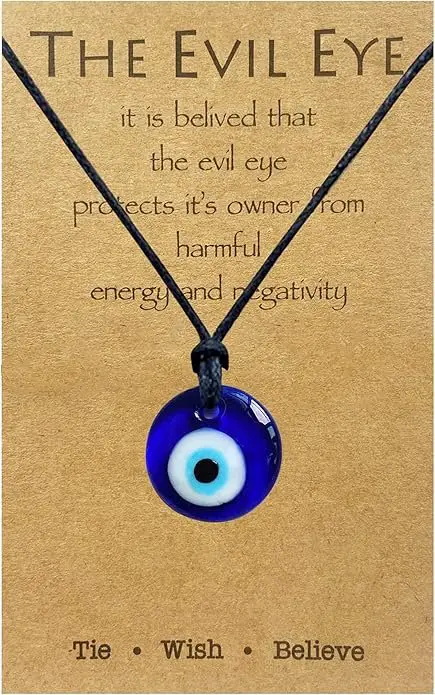

Why Do So Many Successful People Secretly Wear a Little Blue Eye?

Limited time offer: 28% OFF. For thousands of years, the Turkish Evil Eye has quietly guarded wearers from the unseen effects of jealousy and malice. This authentic blue glass amulet on a soft leather cord is the real thing – beautiful, powerful, and ready for you.

Etymology

The name Chimera derives from the Ancient Greek χίμαιρα (Chímaira), which means “she-goat.” This term appears in Homer’s Iliad (circa 8th century BCE), where the creature is described as a monstrous entity with goat-like features integrated into its hybrid body.

The root χίμαρος (chímaros) refers to a male goat, suggesting an association with young or winter-aged livestock, as goats were symbols of seasonal change in agrarian societies.

Etymological links extend to Indo-European words for winter and young animals, such as Old Norse gymbr (yearling ewe) and Latin hiems (winter).

Scholars connect Chímaira to cheîma (winter storm), implying the Chimera evoked images of harsh, unpredictable weather—fitting for a fire-breathing beast that scorched the land. This seasonal connotation may explain its localization in Lycia, where natural gas vents (known today as Yanartaş) produced eternal flames, possibly inspiring the myth.

Variations in spelling and usage appear across ancient texts. Hesiod’s Theogony (circa 7th century BCE) uses Khimaira, emphasizing the goat element, while Latin adaptations—such as Chimera in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (1st century CE)—retain the Greek form but apply it more broadly to fantastical hybrids.

In Etruscan art from the 7th century BCE, the creature is depicted without strict adherence to the Greek model, sometimes with added wings, showing cultural diffusion.

By the Roman period, Pliny the Elder in Natural History (1st century CE) rationalized the Chimera as a misidentified lion species or volcanic phenomenon, shifting the term toward natural history.

Hyginus’s Fabulae (1st century BCE–CE) lists it alongside siblings, using Chimera to denote a hybrid monstrosity. These changes show how the name transitioned from a specific mythological referent to a general descriptor for impossible or composite entities, influencing modern English, where “chimera” means an illusion or genetic hybrid.

In medieval Latin, Chimera appeared in bestiaries as a deceptive beast, blending with Christian allegory.

Renaissance scholars like Cesare Ripa in Iconologia (1593) revived it as a symbol of fraud, depicting it with a human face and a scaly tail.

You May Also Like: 100 Years of Sightings—But What Is Ogopogo Really?

What Does the Chimera Look Like?

Ancient depictions of the Chimera consistently show a lion’s body as the base, with a massive head featuring sharp fangs and a mane. A goat’s head protrudes from the middle of its back, often with curving horns and a beard, positioned between the shoulders. The tail extends as a long serpent, ending in a fanged head capable of independent striking.

In vase paintings from the 7th–6th centuries BCE (such as proto-Corinthian pottery), the creature stands on four lion-like legs, with the goat head angled upward. Fire appears from the lion’s or goat’s mouth, rendered in red-figure style.

Some Etruscan bronzes from the 5th century BCE add wings, though Greek texts omit them. The overall form measures roughly the size of a large lion, with udders on the underbelly indicating its female nature.

Hesiod and Apollodorus describe the hindquarters as draconic in some variants, blending serpent scales with goat fur.

Mythology

The Chimera first appears in Greek mythology as the offspring of Typhon and Echidna, two primordial monsters who challenged Zeus’s rule.

Typhon, a serpentine giant with multiple heads, represented storm and volcanic forces. At the same time, Echidna, half-woman and half-snake, embodied earth’s treacherous depths.

Their offspring included guardians of the underworld and multi-headed serpents, including the Chimera, a terrestrial terror.

The earliest mentions occur in Homer’s Iliad (8th century BCE), Book 6, where King Proetus of Argos exiles Bellerophon to Lycia, and Book 16, which notes that the Chimera was reared by Amisodarus as a scourge to mortals.

Homer calls it “of divine stock, not of men,” with a lion forefront, serpent rear, goat middle, and blazing fire breath. This establishes its hybrid form and destructive role without detailing its birth.

Hesiod’s Theogony (circa 700 BCE) expands the genealogy, listing the Chimera among Typhon’s progeny: “She was a monstrous creature, not of mortal birth, lion in front, snake behind, goat in the middle, breathing the dread might of raging fire.”

Hesiod implies it as Echidna’s child, though some fragments suggest ambiguous parentage. The Catalogue of Women attributes to it offspring like the Sphinx and Nemean Lion via Orthrus, linking it to other heroic labors.

Apollodorus’s Bibliotheca (2nd century BCE) formalizes the lineage: Typhon and Echidna sire the Chimera, which ravages Lycia until Bellerophon slays it.

Hyginus’s Fabulae (1st century BCE–CE) repeats the idea, adding that it breathed fire from all heads.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses (1st century CE) briefly references it in Bellerophon’s tale, highlighting Pegasus’s role.

Geographical connections appear for the first time in Strabo’s Geography (1st century BCE–CE), placing the Chimera near Mount Cragus, possibly inspired by methane flames at Yanartaş.

Pliny the Elder (1st century CE) interprets it as exaggerated tales of local lions. Neo-Hittite sculptures from Carchemish (9th–8th century BCE) show similar lion-goat-serpent figures, suggesting Near Eastern influence predating Greek records.

In later traditions, Virgil’s Aeneid (1st century BCE) stations the Chimera at Hades’ gates, guarding with Cerberus.

Ever Walk Into a Room and Instantly Feel Something Watching You?

Millions have used burning sage to force out unwanted energies and ghosts. This concentrated White Sage & Palo Santo spray does the same job in seconds – just a few spritzes instantly lifts stagnation, breaks attachments, and restores peace most people feel immediately.

Legends

The Slaying by Bellerophon

In the land of Lycia, the Chimera appeared as a relentless destroyer, born from the monstrous pairing of Typhon and Echidna. This beast, with its lion’s frame, goat’s protruding skull, and serpentine tail, scorched fields and devoured herds, leaving villages in ruin.

King Iobates, fearing its wrath yet coveting its end, received the exiled hero Bellerophon from Proetus of Argos. Proetus, slighted by Bellerophon’s refusal of his wife’s advances, had sent the young warrior with a sealed message demanding his death.

Iobates, reading the tablet, devised impossible labors to achieve this. First, he commanded Bellerophon to confront the Chimera, a task no army had survived. The monster lurked in mountain caves, its fire breath igniting forests and its claws rending stone.

Bellerophon, guided by omens from the gods, sought Athena’s aid. The goddess provided a golden bridle, with which he tamed Pegasus, the winged steed sprung from Medusa’s blood.

Mounted aloft, Bellerophon soared above the Chimera’s reach. The beast lunged, its lion jaws snapping and goat head bleating defiance, while the tail serpent hissed venom. Arrows from the hero’s bow struck true, but the creature’s hide repelled them.

Recalling a counsel from a seer, Bellerophon affixed a lump of lead to his spear tip. He thrust it into the Chimera’s flaming maw; the fire melted the metal, which flowed molten down its throat, choking the life from all three heads.

With the monster slain, Iobates set further trials: battling the Solymi tribe, slaying Amazons, and subduing a sea monster. Bellerophon prevailed in each, his fame growing.

Yet hubris followed; he attempted to fly Pegasus to Olympus, earning Zeus’s wrath. The horse bucked, casting Bellerophon to earth, lame and blind, to wander in misery.

The Chimera’s corpse, some say, birthed a spring of healing waters, but its spirit lingered as a warning against overreach.

You May Also Like: Rokurokubi Legends: Women Who Transformed Into Night Demons

Parentage and Siblings in Typhon’s Brood

Typhon, the hundred-headed storm father, rose against Zeus after Hera birthed him in spiteful isolation. Echidna, his mate, slumbered in Arima’s cave, her form fair above and serpentine below.

From their union sprang the Chimera, alongside Cerberus, the Hydra, and Orthrus. Hesiod recounts how Typhon sired these in earth’s secret folds, each a perversion of nature.

The Chimera, least subterranean of the brood, claimed Lycia’s peaks. Unlike Cerberus, who chained the dead, or the Hydra, whose necks regrew in Lerna’s marsh, it roamed free, its fire heralding Typhon’s failed rebellion.

In one variant, the Chimera mated with Orthrus, yielding the Sphinx, who plagued Thebes with riddles, and the Nemean Lion, whose hide Heracles claimed.

Apollodorus details the family’s scope: Typhon assaulted Olympus, hurling mountains, until Zeus’s thunderbolts felled him beneath Etna. Echidna persisted, devouring passersby, until Argus slew her. The Chimera, spared direct divine assault, embodied the remnants of this chaos, its hybrid rage an echo of parental fury.

Scholars note Near Eastern parallels (such as Carchemish’s lion-goat guardians), suggesting that the brood’s motifs traveled from Hittite lore.

In Greek tales, these siblings tested heroes together: Heracles faced the Hydra and the Lion, while Bellerophon’s victory over the Chimera isolated it as a solitary foe.

The Chimera as Omen of Disaster

The Chimera was seen as a sign of disaster. According to the ancient historian Strabo, people claimed to have spotted it near Mount Cragus, where the flames it breathed were thought to foreshadow earthquakes or volcanic eruptions.

Pliny the Elder suggested that these fears were linked to actual fiery vents at a place called the “Chimaera Promontory,” which both guided sailors and scared local herders.

In other stories, such as those by Hyginus, the Chimera’s roars were said to bring on storms, linking it to the powerful giant Typhon. The poet Ovid mentioned that defeating the Chimera calmed the chaos it brought. At the same time, Virgil described it as haunting the underworld, where it burned the souls of those who tried to escape.

One ancient poem hints that the Chimera may have also appeared during the Trojan War, casting a shadow over ships and signaling doom.

Local customs suggested that offering goats to the Chimera might keep it at bay for a while, but if ignored, it would strike back.

After Bellerophon defeated the beast, the people of Lycia built altars in his honor, believing that the hero’s victory, aided by the flying horse Pegasus, marked the end of such monstrous threats.

You May Also Like: The Mare: The Nightmare Monster That Crushes Men in Their Sleep

Chimera vs Other Monsters

| Monster Name | Origin | Key Traits | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chimera | Greek | Lion-goat-serpent hybrid; fire-breathing | Aerial assaults; molten lead |

| Manticore | Persian | Lion body, human head, scorpion tail; poisonous spines | Decapitation; vulnerable eyes |

| Sphinx | Greek/Egyptian | Lion body, eagle wings, human head; riddles | Solved riddles; self-destruction |

| Griffin | Greek/Scythian | Lion body, eagle head/wings; treasure guardian | Heavy armor; ground combat |

| Hydra | Greek | Multi-headed serpent; regenerative necks | Cauterized stumps; single immortal head |

| Cerberus | Greek | Three-headed hound; underworld guardian | Honeyed cake; sleep induction |

| Minotaur | Greek | Bull-headed man; labyrinth dweller | Sword strikes; navigation aid |

| Harpie | Greek | Bird-woman hybrid; storm winds, theft | Bound wings; confined spaces |

| Nue | Japanese | Monkey head, tanuki body, tiger legs, snake tail; illness-bringer | Arrows from above; exorcism |

| Ammit | Egyptian | Crocodile head, lion body, hippo rear; soul devourer | Divine judgment; heart scales |

| Tarasque | French | Dragon-turtle hybrid; fire and flood | Prayer and taming; relics |

The Chimera shares a hybrid composition with many monsters, emphasizing chaos through mismatched animal parts, as seen in the Manticore’s predatory arsenal or Nue’s vengeful form.

Similarities lie in their roles as regional terrors—devouring livestock like the Minotaur or guarding realms like Cerberus—often requiring heroic intervention with clever tactics. Fire-breathing aligns it with Tarasque’s elemental fury, while the Sphinx’s riddle-like intellect contrasts with its brute force.

However, the Chimera embodies volcanic unpredictability, unlike Ammit’s judicial finality or Harpies‘ thieving winds. Greek kin like Hydra focus on regeneration over multiplicity, and non-Greek variants like Nue introduce supernatural malaise rather than direct combat.

Overall, the Chimera’s defeat via aerial strategy highlights human ingenuity, a theme echoed but varied across cultures, from divine scales for Ammit to taming for the Tarasque.

Powers and Abilities

The Chimera has some amazing and fearsome abilities. The lion part of the Chimera gives it incredible strength, allowing it to charge at and attack its prey. The goat head adds extra strength and can bite, while the snake tail can strike with venom, leaving its victims paralyzed.

One of the most terrifying features of the Chimera is its ability to breathe fire. Whether from its lion mouth or goat head, this fire could easily set forests ablaze or even melt metal!

These combined abilities make the Chimera a formidable opponent. The lion would hold enemies down, the goat could attack from a distance with its fire, and the snake’s tail could catch anyone trying to escape. Being a child of the giant

The Chimera’s powers and abilities include:

- Fire-Breathing: Can breathe fire, burning everything in its path and even melting metal into dangerous shapes.

- Enhanced Strength: Has the strength of a lion, capable of breaking through armor and knocking down buildings.

- Venomous Bite/Sting: Its snake-like tail can inject a poison that paralyzes enemies, while its lion and goat heads can deliver deadly bites.

- Multi-Headed Assault: Each head can act independently, allowing for coordinated attacks and making it hard for opponents to escape.

- Resilience: With the endurance of a goat, it can take a lot of damage from weapons, and its tough skin can withstand arrows.

- Omen Projection: Its appearance often signals upcoming disasters, like volcanic eruptions, spreading fear among those who see it.

You May Also Like: Was the Kraken Real? The Origins of a Norse Horror Legend

Can You Defeat a Chimera?

Defeating the Chimera required exploiting its ground-bound nature and fiery weakness, as no direct confrontation succeeded without aid. Bellerophon’s method—attacking from Pegasus’s height—evaded its claws and flames, allowing precise strikes. Archers or spearmen on elevated terrain could replicate this, targeting the softer goat head or eyes.

The lead-tipped weapon proved decisive: thrust into the breathing maw, it liquefied and choked the beast internally. Alternatives included flooding its lair to drown the serpent’s tail or using reflective shields to redirect fire back upon it. Divine favor, like Athena’s bridle, enhanced odds, but mortal cunning sufficed in variants where Bellerophon used traps or poisoned bait.

Post-defeat, the Chimera’s head served as a trophy, warding off similar threats. In Lycian practice, altars and vows to Zeus prevented resurgence, emphasizing ritual prevention over repeated combat.

Conclusion

The Chimera is a powerful symbol from Greek mythology. Representing the clash of different forces in nature, it reminds us of both beauty and danger.

This mythical beast has left a mark on history that goes beyond stories—it has influenced art, from ancient pottery to modern science, where the term “chimera” is used to describe things made up of different parts.

At its core, the Chimera’s tale is about resilience: a brave hero, with clever plans and help from others, managed to overcome chaos. This story offers valuable lessons on how to face overwhelming challenges.